- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Crosslinguistic Influence in Language and Cognition

About this book

A cogent, freshly written synthesis of new and classic work on crosslinguistic influence, or language transfer, this book is an authoritative account of transfer in second-language learning and its consequences for language and thought. It covers transfer in both production and comprehension, and discusses the distinction between semantic and conceptual transfer, lateral transfer, and reverse transfer. The book is ideal as a text for upper-level undergraduate and graduate courses in bilingualism, second language acquisition, psycholinguistics, and cognitive psychology, and will also be of interest to researchers in these areas.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Crosslinguistic Influence in Language and Cognition by Scott Jarvis,Aneta Pavlenko in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Overview

1.1. INTRODUCTION

Crosslinguistic influence—or the influence of a person’s knowledge of one language on that person’s knowledge or use of another language—is a phenomenon that has been of interest to laypeople and scholars alike since antiquity and most likely ever since language evolved. One of the earliest references to language contact, bilingualism, and crosslinguistic influence comes from Homer’s Odyssey, where Odysseus tells Penelope about the “mixed languages” of Crete. Due to widespread multilingualism in the ancient world, instances of crosslinguistic influence abound in a variety of ancient texts, ranging from epitaphs and personal letters, to legal and commercial documents, to religious and literary treatises (Adams, Janse, & Swain, 2002). These texts also offer evidence of negative attitudes towards the phenomenon of transfer (another term for crosslinguistic influence), such as derogatory remarks about “speakers of bad Greek” made by ancient writers and philosophers, including Homer, Herodotus, and Flavius Philostratus. In fact, Janse (2002) argues that the negative term barbarians and its derivatives were commonly used to refer not only to speakers of languages other than Greek but also to foreigners speaking “bad Greek” or, in our contemporary terms, foreigners exhibiting first language transfer.

The trend of seeing language transfer as a negative phenomenon, associated with low moral character and limited mental abilities, persisted all the way into the twentieth century when increased global migration fueled the fear of foreigners and of the unspeakable things they could do to one’s language. In a speech delivered in 1905 to the graduating class of Bryn Mawr College, Henry James, traumatized by his recent visit to Ellis Island and to the Lower East Side, populated by recently arrived Eastern European immigrants, warned the students against an imminent threat to the civilized tongue from

the vast continent of aliens whom we welcome, and whose main contention…is that, from the moment of their arrival, they have just as much property in our speech as we have, and just as good a right to do what they choose with it. (cited in Brumberg, 1986, pp. 6–7)

In reality, it was the immigrants’ native language that was in danger of second language influence. This influence is well-documented in Mencken’s (1937) monumental treatise The American Language. Mencken’s discussion of the influence of English on the immigrants’ native languages offers a glimpse of the interest that lexical (word-related) and syntactic (grammar-related) transfer from the second language to the first elicited in the scholarly community. At the same time, many scholars and writers of the era, including some well-educated immigrants, frowned on both first and second language transfer. Marcus Ravage, a well-known writer and himself a Romanian immigrant, criticized the influence of Yiddish and Romanian on his fellow Romanians’ English:

My friends were finding English contemptibly easy. That notion of theirs that it was a mixture of Yiddish and Rumanian, although partly justified, was yielding some astonishing results. Little Rumania was in throes of evolving a new tongue – a crazy-quilt whose prevailing patches were, sure enough, Yiddish and Rumanian, with here and there a sprinkling of denatured English. They felt no compunction against pulling up an ancient idiom by the roots and transplanting it bodily into the new soil. One heard such phrases as “I am going on a marriage,” “I should live so,” “a milky dinner.” (Ravage, 1917, p. 103)

Ravage’s concerns were echoed by another well-known immigrant writer of the era, Abraham Cahan, who poked fun at the lexical and syntactic influence of English on the immigrants’ Yiddish:

I have already described how the Yiddish of American-born children grated on my ears. The Americanized Yiddish of the immigrants, studded with English expressions, was no better. My anger rose when I heard such expressions as “er macht a leben” (he makes a living) or “er is vert tsehn toisend dolar” (he is worth ten thousand dollars). Or such horrors as “vindes” (windows) or “silings” (ceilings) and “pehtaytess” (potatoes). (Cahan, 1926, pp. 241–242)

These examples serve to show that, in the absence of an in-depth understanding of the workings of language, transfer phenomena often came to signify sloppiness, narrow-mindedness, and lack of mental clarity and sound thinking. Linguists and psychologists often contributed to this picture, arguing, for instance, that the mutual interference of languages represents a danger to sound thinking (Epstein, 1915) and that first language transfer in pronunciation is due to the learners’ laziness and lack of interest in changing their phonological behavior (Jespersen, 1922). These convictions were not truly challenged until the 1940s and 1950s, when the work of Charles Fries (1945), Uriel Weinreich (1953), Einar Haugen (1953), and Robert Lado (1957) moved discussions of language transfer to a scholarly footing, legitimizing transfer as an unavoidable feature of language learning and use and exploring it as a linguistic, psycholinguistic, and sociolinguistic phenomenon. Weinreich’s work in particular was groundbreaking in terms of both the breadth and depth of the empirical evidence he examined, and in terms of the insights he offered about the nature of CLI. His book Languages in Contact (1953) is still frequently cited in transfer research.

Since the 1950s, a number of additional books have dealt extensively with transfer, including, in chronological order, Vildomec (1963), Gass and Selinker (1983), Kellerman and Sharwood Smith (1986), Ringbom (1987), Dechert and Raupach (1989), Odlin (1989), Gass and Selinker (1992), Sjöholm (1995), Jarvis (1998), Kecskes and Papp, Cenoz, Hufeisen, and Jessner (2001, 2003), Alonso (2002), Cenoz, Hufeisen, and Jessner (2003), Cook (2003), Arabski (2006), and Ringbom (2007). Of these, Odlin’s book stands out as having provided the broadest synthesis of the transfer literature to date. The present book is not intended as a replacement for Odlin’s. Rather, our aim is, first, to characterize the new developments that have taken place in transfer research since the publication of his book and, second, to link these developments to ongoing interdisciplinary inquiry into language and cognition. The scope of our book is also somewhat narrower than Odlin’s in that we deal with transfer almost exclusively in relation to adult second language users, and almost exclusively as a psycholinguistic phenomenon—or as a phenomenon that takes place in the minds of individuals, and which is subject to the effects of various cognitive, linguistic, social, and situational factors. In this book, therefore, we do not delve into issues related to child bilingualism, transfer as a societal phenomenon, or code-switching.

We use the terms transfer and crosslinguistic influence interchangeably as theory-neutral cover terms to refer to the phenomenon in question, even though we recognize that by the 1980s some researchers no longer considered the term “transfer” to be a suitable label for the phenomenon because of its traditional association with the behaviorist notion of skills transfer (see Lado, 1957, p. 2; Odlin, 1989, p. 26; Osgood, 1953, p. 520; Selinker, 1983, p. 34). Interference is another term that has often been used since Weinreich (1953), but this term also carries behaviorist connotations and additionally has the disadvantage of directing one’s attention only to the negative outcomes of transfer. In the mid 1980s, Kellerman and Sharwood Smith (1986) proposed the term crosslinguistic influence as a theory-neutral term that is appropriate for referring to the full range of ways in which a person’s knowledge of one language can affect that person’s knowledge and use of another language. This term has since gained general acceptance in the fields that investigate this phenomenon, even though the terms “transfer” and “interference” have continued to be used synonymously with it. More recently, some scholars have suggested that even “crosslinguistic influence” may be an inappropriate term to refer to the phenomenon, given that the influence of one language on another in an individual’s mind may be more an outcome of an integrated multicompetence than of the existence of two (or more) completely separate language competences in the mind (e.g., Cook, 2002). We discuss this perspective more fully in section 1.6 of this chapter, and in the meantime simply state that although the suitability of the terms “transfer” and “crosslinguistic influence” can certainly be called into question, these are at present the most conventional cover terms for referring to the phenomenon, and are the terms that we will use throughout this book. The term first language (L1) will be used to refer to the first language acquired by the speaker from a chronological perspective, even if this language is no longer the speaker’s dominant language. The term second language (L2) will refer to any language acquired subsequently, regardless of the context of acquisition or attained level of proficiency.

The two primary aims of the present chapter are to provide a brief historical perspective of the important developments that took place in the transfer research prior to the 1990s (or prior to the 1989 publication of Odlin’s book), and to offer a summary of the new developments that have taken place since the beginning of the 1990s. We begin with the historical perspective in section 1.2 by describing the four general phases through which the investigation of a psycholinguistic phenomenon logically progresses, and by discussing which of these phases transfer research has already passed through, and where it now stands. In section 1.3, we discuss some of the historical skepticism about the scope and importance of transfer, and explain why much of the skepticism was unwarranted and why it has largely given way to a general recognition of both the importance and the complexity of the phenomenon. Section 1.4 concludes our description of the historical perspective by outlining what we consider to be the primary landmark findings of the pre-1990s transfer research. In section 1.5, we turn to a summary of the important developments that have taken place in crosslinguistic influence (CLI) research since the beginning of the 1990s, giving special attention to new areas of empirical investigation. Section 1.6 continues our summary of recent developments by focusing on new theoretical accounts of CLI that have arisen since the beginning of the 1990s. Finally, in section 1.7, we draw together the historical and recent perspectives by clarifying the relationship among the different types of CLI that have been referred to throughout the literature.

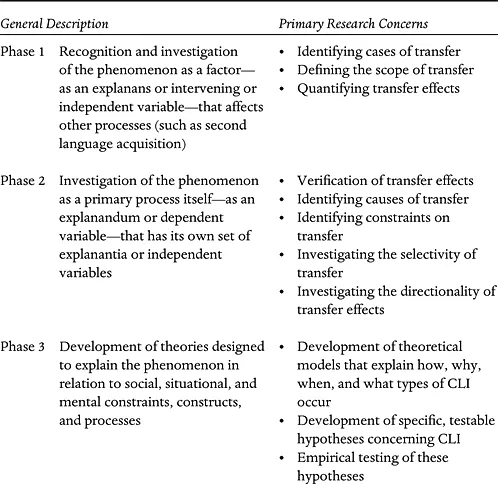

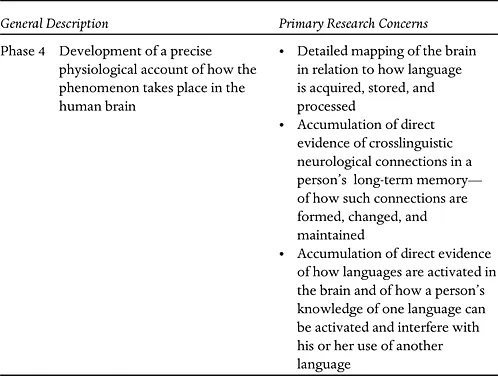

1.2. PHASES OF TRANSFER RESEARCH

Transfer research, like the investigation of various other phenomena in language and cognition, can be described as progressing through four general phases. During Phase 1, the phenomenon in question gains recognition as a possible explanans (explanation, affecting factor, or independent variable) for what is considered to be a more important explanandum (thing to be explained, or dependent variable). Next, during Phase 2, the phenomenon in question comes to be considered important enough to be investigated as an explanandum in its own right, with its own set of empirical explanantia (or factors that affect its behavior). Then, in Phase 3, the phenomenon attracts sufficient theoretical interest to give rise to sophisticated competing theoretical models and hypotheses concerning the social, situational, and mental constraints, constructs, and processes involved in the occurrence of the phenomenon; empirical research during this phase is thus highly theory-driven. Finally, Phase 4 is characterized by a complex understanding of the phenomenon in terms of the actual neurophysiological structures and processes through which it operates. These phases and their primary characteristics are listed in Table 1.1.

TABLE 1.1 Phases of Transfer Research

|

|

From our perspective, Phase 1 of transfer research began when transfer became widely recognized as a variable that can affect language acquisition, language use, and other linguistic, psychological, cognitive, and cultural processes. Its beginning was marked by the recognition of transfer as an intervening variable in language acquisition and language change, and this was followed by studies that examined transfer in a more controlled way as a moderator or primary independent variable (for a description of different types of variables, see, e.g., Hatch & Lazaraton, 1991, pp. 63–68). It is difficult to put an exact date on the beginning or end of the first phase. It may havebegun informally centuries ago, but its beginning was clearly underway in the mid to late 1800s with studies by Müller (1861) and Whitney (1881), and a little later by Epstein (1915) and others (see, e.g., Odlin, 1989, pp. 6–9). Perhaps the most substantial contribution to Phase 1 occurred in the 1950s in the form of Weinreich’s (1953) detailed examination of numerous types of transfer (which he called interference), and his discussion of methods for identifying and quantifying transfer and its relationship to other aspects of bilingualism. Phase 1 continued at least until the mid 1970s, and remnants of this phase can still be seen in some of the transfer research today. The issues that were fundamental to researche...

Table of contents

- Contents

- Tables and Figures

- Preface

- CHAPTER 1 Overview

- CHAPTER 2 Identifying Crosslinguistic Influence

- CHAPTER 3 Linguistic Transfer

- CHAPTER 4 Conceptual Transfer

- CHAPTER 5 Conceptual Change

- CHAPTER 6 Transferability and Factors that Interact with Transfer

- CHAPTER 7 Conclusions

- References

- Name index

- Subject index