1

The American school of IPE

Daniel Maliniak and Michael J. Tierney

D. Maliniak and M.J. Tierney (2009) ‘The American school of IPE’, Review of International Political Economy 16(1): 6–33, published by Taylor & Francis Ltd, http://www.informaworld.com. Permission has been granted by the publisher.

In a keynote speech to the inaugural meeting of the International Political Economy Society (IPES) at Princeton University in November 2006, Benjamin Cohen argued that there were at least two distinct schools of thought that have adopted the moniker ‘IPE’ (international political economy) – the ‘British school’ and the ‘American’ school.1 According to Cohen, the intellectual evolution of the IPE field has produced an American school characterized by ‘the twin principles of positivism and empiricism’ and a British school driven by a more explicit normative, interpretive, and ‘ambitious’ agenda (Cohen, 2007: 198–200). These schools diverge in the ontologies, epistemologies and normative stances that each employs to study the same subject – ‘the complex linkages between economic and political activity at the level of international affairs’ (Cohen, 2007: 197). In Cohen’s view, IPE is increasingly fractured along conceptual and geographical lines, yet the American and British schools remain complementary. As such, he ends his reflection on IPE’s transatlantic divide by calling for mutual respect, learning and a ‘meeting of the minds’ (Cohen, 2007: 216–17).

Cohen’s speech, subsequent article in this journal (Cohen, 2007), and book (Cohen, 2008) have sparked a vibrant and contentious debate on the origins, character, and even desirability of a transatlantic IPE divide.2 Our reaction was less visceral than most. Nonetheless, we were provoked by Cohen’s depiction of the field and inspired to treat his characterizations of each school, based upon his interpretive intellectual history, as hypotheses that merit further testing. This interest coincided with our ongoing project on Teaching, Research, and International Policy (TRIP): a multi-year study of the international relations field in the United States and Canada. In the TRIP project, we employ data gathered from two extensive surveys of international relations (IR) scholars and a new journal article database that codes all the articles in the 12 leading political science journals that publish articles in the subfield of IR. Our journal article database covers the years between 1980 and 2006 (see below for note on methodology). While the TRIP project was not designed to provide the definitive test of Cohen’s thesis, it does provide us with some leverage on his claims. More importantly, since the TRIP project utilizes distinctive data collection, coding, and analysis methods – compared to Cohen’s methods – it provides a potentially powerful cross-check on Cohen’s findings about the nature of the IPE subfield and its purported divide.

Thus, the purpose of this article is to use the TRIP data to investigate the American IPE school upon which much of Cohen’s argument is premised and from which the lively discussion surrounding the American versus British school has sprung. Ultimately, unlike Cohen, we do not seek to persuade others of the existence of stark differences between IPE scholarship in the United States and Europe. Indeed, our data are limited to IPE scholars in the United States and Canada and to the top journals in the field of IR (as determined by their Garand and Giles impact scores).3 Thus we consciously refrain from making assertions about the nature of the British IPE and the existence or nature of any transatlantic divide.4 Moreover, we remain agnostic about the prospects or desire for transatlantic bridge building within IPE (we leave this debate to others, including those who are contributing to this special issue of RIPE). Yet we are convinced that good bridges require solid foundations; and solid foundations require a clear understanding of the shores on which the foundations are built. Using the TRIP data, we can at least say something systematic about the American shore.

We have two specific objectives in this article. The first is to ‘test’ specific hypotheses derived from Cohen’s argument. If Cohen’s depiction of the American IPE school is consistent with the results of our survey and patterns of journal article publications, then his broader thesis about the IPE subfield are further validated and the implications of his argument merit the animated debate that we have already witnessed. If Cohen’s depictions are not consistent with our findings, we should question his underlying assumptions and direct further research into the ‘myth’ of the divide – questioning why some perceive a divide that is non-existent or quite small.

Our second objective is to use the TRIP data to assess prominent trends in American – and to a lesser extent Canadian – IPE. The TRIP project is well equipped to do this, insofar as it is quite broad in scope. The survey questions and variables coded in the journal article database capture the essential human and institutional ‘demography’ of the IR field, as well as the paradigmatic, theoretical, methodological, and epistemological orientation of that field. We can parse out variables most relevant to the American IPE subfield. In doing so, we reveal some remarkable and sometimes surprising findings that raise numerous questions directly relevant to understanding the state of IPE in the United States and its place within the broader IR discipline. In this paper, we take particular note of four trends in American IPE: its institutional and human demography, its ‘paradigmatic personality’, the growing methodological homogeneity, and the surprising absence of any ‘ideational turn’ which is so prominent in the other subfields of IR.

We expect this paper to generate more questions than answers. While some of our data is formatted so that it directly speaks to extant hypotheses, much of what follows simply describes patterns of behavior, publication, or the aggregated opinion of IPE scholars in the United States and Canada. We were quite surprised by some of our findings and expect them to provoke a variety of explanations, reflections on the past, and consequences for the future of the discipline.

Brief note on project methodology

In order to describe the American school of IPE we utilize the Teaching and Research in International Policy (TRIP) project’s databases.5 First, we employ results from two surveys: one of American IR scholars from 2004 and one of American and Canadian scholars surveyed in 2006 in order to describe the research practices of IPE scholars in those institutions.6 We also report United States IPE scholars’ views on the broader IR discipline and on some pressing foreign policy issues. In order to distinguish IPE scholars from the broader IR community, we often compare the responses of these two groups. Second, we use the TRIP journal article database, which covers the top 12 journals in political science that publish research on international relations. The time series spans 1980–2007 (Maliniak et al., 2007a).7 Since publication in these journals is not limited to American IPE, this data source – unlike the survey – can help to describe both the American and British schools of IPE.8 The article database reveals which of the top 12 journals publish the most (and most cited) articles within the IPE subfield. This database also allows us to identify trends in the substantive focus of IPE research, the rise and fall of paradigms in the IPE literature, the methods employed most frequently, direct comparisons between the IPE literature and the broader IR literature, and whether IPE generates theory and methods that diffuse into the rest of the IR literature or vice versa.

In addition to a description of the American IPE subfield, we employ the TRIP journal article database in order to provide some preliminary tests of Cohen’s comparative hypotheses. Are non-American IPE scholars publishing work that is substantially different from their American IPE cousins? Is American work more positivist, quantitative and formal, while British and European IPE is more non-positivist, normative, and qualitative? If these claims are true on average, how large are the differences between American and British styles of IPE and are these differences growing or shrinking? While Canada is not in Europe, some preliminary research suggests that it may be somewhere between United States and Britain in terms of the sensibilities of scholars located there and in terms of the research they produce. The 2006 TRIP Survey included IR and IPE scholars at Canadian universities and they appear to fit more comfortably in Cohen’s ‘British school’ than in the American one right next door.

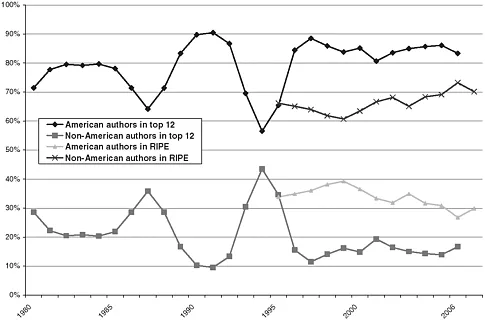

The journals in the TRIP database are dominated by scholars at American institutions. One bit of evidence suggesting that there are two distinct IPE communities is the pattern of publication displayed in Figure 1.1. When we compare

the percent of authors at non-US institutions in our sample to those publishing in RIPE, we see a dramatic difference. For every year over the past decade we observe less than 20% of non-US authors publishing IPE articles in the top 12 journals. This differs dramatically from the distribution of articles at RIPE, where we never observe less than 60% of non-US authors. Over the past ten years the percentage of US-based authors publishing in RIPE has dropped from around 40% to just 30%. So, if we accept the Murphy and Nelson characterization of RIPE as the flagship journal of British style IPE, then we have some evidence for a large and growing gap between British IPE and IPE published in the other leading journals.

The field: what does American IPE look like?

The demography of American IPE

How do IPE scholars differ from the rest of the field of international relations within the United States? Using answers to the TRIP surveys allows us to measure specific characteristics of the individuals who make up the IPE subfield. In some respects scholars who claim IPE as their primary or secondary issue area differ from the broader population of IR scholars, but in other ways they are indistinguishable. IPE scholars are trained at different schools, they use different methods, they study different regions of the world, and they come from different regions of the world (specifically, they are far more international than their other IR colleagues at United States institutions). However, in other respects where we might expect variation across areas of study, we see very little. The percent of men and women studying IPE as IR is basically the same; IPE scholars are the same age on average as their IR counterparts, and they rank journals, PhD programs, and threats to United States national security about the same as the broader IR community. Overall, 30% of IR scholars in the United States do work in IPE.9

Specific schools have reputations for being particularly strong in IPE (Harvard, Berkeley, Princeton, UCSD, and UCLA often get mentioned at the American Political Science Association (APSA) bar), but the conventional names today are not always the same programs that have produced the largest number of IPE scholars in the United States over the past 40 years. At minimum, this variation suggests that comparative advantages within the top PhD programs change over time.

Table 1.1 Departments training the most IPE scholars

Table 1.2 Departments training the most IR scholars

Table 1.3 Number of IPE articles produced since 1980

Although only 2% of all IR scholars received their doctoral training from Yale University, more IPE scholars (5%) trained at Yale than any other program. In addition to Yale, several other institutions have produced proportionately more IPE scholars than IR scholars studying in other issue areas. For example, University of Wisconsin at Madison ranks fourth for IPE but only 13th overall, Princeton University is tied for tenth with University of North Carolina, but these two schools rank 15th and 26th in terms of the total number of IR scholars produced.

In addition to what universities are training the next generation of graduate students, the article database reveals which programs produce the most IPE articles in the top 12 journals. We code the home department of authors upon publication of their article, and find that Harvard tops the list, with its scholars having penned 5% of all the IPE articles in the top journals since 1980. The top three schools for IPE are the same programs in order as IR generally. Strikingly, University of Colorado is tied for third in IPE articles, yet is 11th for the broader IR category.10

IPE scholars at United States institutions are neither younger, nor more diverse in terms of their gender than other IR scholars. On average, IPE scholars received their PhD two years later (1992) than the broader group of IR scholars. This is somewhat surprising, since both groups have the same average age, which implies that IPE scholars either start graduate programs at a later age or they take longer to obtain their degree than other IR scholars. However, the late start or extended stay in graduate school may pay off later as IPE scholars are more likely to hold the position of full professor (37%) than those studying in other subfields (33%).

Similarly, we find no evidence of a gender distinction within IPE that is different than the general IR population.11 While the percentage of women in IR as a whole is 23%, the percent who study IPE is only 22%. Research on publication rates in political science and IR demonstrate that women publish less than their male colleagues and IPE provides no exception to this trend. Since the year 2000 only 14% of all authors of IPE articles published in the leading journals were women. Despite this fact, there is strong evidence from the TRIP survey that IPE scholars value the research of women to a greater extent than other IR scholars do. More women appear in the various top 25 lists for greatest impact on the field (3), most interesting work (6) and most influential on your own research (4). In all three of these categories IPE scholars are more likely to list women than are IR scholars who study other issue areas.12

Where is IPE research published?

Within the IR literature, articles with an IPE focus make up only 13% of those published since 1980 (despite 30% of IR scholars in the United States reporting their first or second field as IPE). Over this period, IPE’s share of articles in the top 12 journals has ranged from a high of 20% in 1984 and 1985, to a low of 5% in 1994. Within the journals analyzed there is significant variation. Thirt...