CHAPTER 1

Introduction

Since its invention by Tim Berners-Lee in 1990, the web has rapidly transformed the means by which information can be published and disseminated. Central to the original ideal of the web was the ability to transfer data regardless of the platform on which it was viewed: so long as a visitor had a browser, it did not matter which hardware or operating system he or she used to get online.

Since about 2004, however, the ease and capabilities of the web have undergone considerable changes—what is commonly referred to as Web 2.0. This chapter will begin with an outline of the principles of Web 2.0 publishing, as well as the various options open to web producers.

THE INTERNET AND WEB 2.0

Web 1.0

There are plenty of books that have appeared in recent years on the history of the internet. As the focus of this title is recent developments that have been bundled together under the title ‘Web 2.0’, the context of web development throughout the 1990s can be dealt with very quickly.

The beginnings of the internet, as opposed to the world wide web, lie in the Cold War and plans to build a communications structure that could withstand a strategic nuclear attack. DARPANET (the US Department of Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) launched the first network in 1968, and through the 1970s and 1980s various research and military institutions connected to this backbone.

Until 1990, however, the internet was still very much an esoteric and restricted concern. What changed this was the work by Tim Berners-Lee, a consultant at the European Centre for Nuclear Research (CERN), who wrote a short program, Enquire-Within-Upon-Everything, or ENQUIRE, that enabled electronic documents to be linked more easily. A year later, he developed the first text web browser, NeXT, and so launched the world wide web.

CERN continued to develop the web as an academic tool, but by the end of 1992 only 26 hosts were serving websites, growing slowly to 1,500 by 1994. The boom in web (and internet) usage came that year when Marc Andreessen, at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications, developed a graphical web browser, Mosaic, and then left to form a new company, which was to become Netscape Communications.

At the same time, developments in personal computing, such as the decline in price of PCs and the launch of a new operating system, Windows 95, meant that more people than ever before were starting to use computers as part of their daily lives. While Microsoft had originally been dismissive of the internet, by 1997, with the launch of Internet Explorer 4 as part of the Windows operating system, they began to pursue this new market much more aggressively (too aggressively according to the US Department of Justice).

The late 1990s saw the dotcom bubble expand—and then burst. Paper millionaires appeared and disappeared in the space of a few months, and a post-millennium malaise set in when it seemed for a few years that nothing good could come out of the overvalued medium.

Core principles of Web 2.0 include using the web as a platform to run applications, rather than relying on the operating system, allowing users to take control of their content, and employing new methods to share that content more easily.

Yet the investment and innovation that took place in those years did have some incredibly important consequences. While many half-baked websites (quite rightly) disappeared without trace, some such as Amazon, eBay and Google became household names. Internet usage generally, and the web in particular, had become completely normalised in many instances, for some users displacing traditional media altogether as faster broadband connections rolled out in different parts of the world. At the same time, the often difficult process of getting content online was becoming increasingly simplified through such things as blogs, wikis and social networking sites, leading some commentators to remark on a new phase of web publishing—Web 2.0.

What is Web 2.0?

Web 2.0 is a term coined by Dale Dougherty of O’Reilly Media and Craig Cline of MediaLive prior to a conference of that name which took place in 2004. It is a rather loose term that refers to a collection of platforms, technologies and methodologies that represent new developments in web development.

The term itself has generated a considerable amount of controversy, most notably from Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the world wide web, who, in an interview for IBM in 2006, remarked that ‘nobody even knows what it means’. Berners-Lee pointed out that the innovations implemented by Web 2.0 applications, for example simplifying the sharing of data and making online media much more inclusive, were actually pioneered as part of the development of the supposedly outdated Web 1.0. Likewise, Steve Perlman (the man behind QuickTime as well as many other innovations) more recently observed that many so-called Web 2.0 sites were really very static in their approach to content and lacked real multimedia support; many such applications, he observed in an interview with CNET, currently touted as cutting edge will be obsolete in only a few years.

In addition to such criticism, a more general observation is that certainly much Web 2.0 commentary is little more than internet marketing hype familiar from the dotcom bubble at the end of the 1990s. Despite these reservations (all of which are extremely valid), Web 2.0 is a convenient label to distinguish some real innovations that have taken place since the turn of the century. More than this, however, it recognises that recent years have seen a remarkable change in the applications of new technologies driven (among other things) by revolutions in computer usability and bandwidth.

In a blog entry in September 2005, Tim O’Reilly offered a succinct overview of what Web 2.0 was meant to achieve, observing that ‘like many important concepts, Web 2.0 doesn’t have a hard boundary, but rather, a gravitational core. You can visualise Web 2.0 as a set of principles and practices that tie together a veritable solar system of sites that demonstrate some or all of those principles, at a varying distance from that core’ (O’Reilly, 2005).

Key elements of this ‘gravitational core’ include:

- ■ using the web as an applications platform,

- ■ democratising the web, and

- ■ employing new methods to distribute information.

The implications behind a ‘democratisation’ of the web are contentious to say the least, and this idea is better limited to considerations of usability and participation rather than any implied political process (although that is often invoked), but these three bullet points in some shape or form do identify the nucleus of what Web 2.0 is meant to achieve with regard to platforms, participation, and data as the focus.

The web as platform

O’Reilly observes that the notion of the web as platform was not new to Web 2.0 thinking but actually began with Netscape in the mid-1990s when it took on Microsoft with the assertion that online applications and the web would replace Windows as the key operating system (OS). As long as users could access programs and data through a browser, it did not really matter what OS or other software was running on their desktop computer.

Web 2.0 platforms are designed to make data accessible, regardless of its location, so that it can be exchanged as seamlessly as possible, providing services previously carried out on the desktop.

Several factors indicate the difference between online services in the 1990s and those currently labelled as Web 2.0, and also indicate why Netscape failed at the time:

- ■ Limited bandwidth: for processing and delivering data, online services simply lagged behind and/or were too expensive in comparison to desktop applications at the time.

- ■ Limitations of the ‘webtop’: Netscape’s alternative to the desktop, the ‘webtop’, was much closer to Microsoft’s core model than it assumed; achieving dominance by giving away a free web browser was meant to drive consumers to expensive Netscape server products rather than allowing them to plug into a range of services. The software application had to succeed for Netscape to be viable.

O’Reilly contrasts this approach to that of Google’s, which began life as a web service: the ultimate difference, argues O’Reilly, is that with Google the core service is combined with the delivery of data: ‘Without the data, the tools are useless; without the software, the data is unmanageable’ (2005). Software does not need to be sold and licensing of applications is irrelevant, because its only function is to manage data, without which it is redundant: that is, it ‘performs’ rather than is distributed. As such, ‘the value of the software is proportional to the scale and dynamism of the data it helps to manage’. Furthermore, data should be as easily exchanged as possible between different applications and sites.

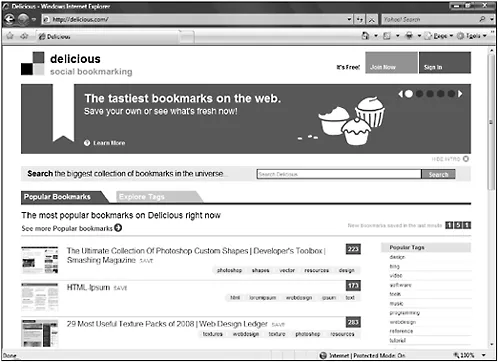

Rather than simply providing static information as was common to many (but by no means all) Web 1.0 sites, Web 2.0 services make much greater use of applets to use that data dynamically, for example to send messages to large numbers of users via a simple interface (Twitter) or share favourite links (delicious). Simplicity of use to the end user often belies very complex technology behind the scenes, and core technologies include server software, content syndication, messaging protocols, standards-based browsers (non-standard plug-ins are to be avoided as they cannot necessarily be installed on different devices) and client applications accessed through the browser.

The important features of the web as platform are as follows:

- ■ to make data accessible from any platform connected to the internet, regardless of its location or the operating system,

- ■ to exchange that data as seamlessly as possible between different sites and applications, without the need for proprietary plug-ins,

- ■ to carry out tasks previously carried out on the desktop via an online service and thus make them more easily shared,

- ■ to use applets to provide a ‘user rich experience’.

delicious.com, one of the new generation of social bookmarking sites.

An architecture of participation

The ‘democratisation of the web’ is a phrase often used in conjunction with Web 2.0, but one that Producing for Web 2.0 will avoid because of the assumptions it makes about democratic processes as ultimately being tied too often to consumption (this is not to deny a link between the two, but rather to draw attention to the limitation of such connections, a full analysis of which is beyond the scope of this book).

Rather, here we will use a more neutral term, again first used widely by Tim O’Reilly but with its roots in open-source software development and the ideas of Lawrence Lessig—an ‘architecture of participation’. Such participation builds upon the interactivity that was an early part of web design, in contrast to other media which tend to emphasise passive consumers (not necessarily in interpretation, but certainly in terms of production) versus active producers. Despite the fact that Berners-Lee believed that early users would be authors as well as readers, and nearly every site had pages that required users to click hyperlinks to navigate a site, most such pages were very static.

In the mid-1990s, however, companies such as Amazon were actively encouraging visitors to post reviews of books, and of course there had long existed interactivity on such things as bulletin boards which started to transfer to mainstream sites. The development of audience interactivity, then, can be seen as an evolution of early forms of connecting people (as pointed out by Berners-Lee), emphasising the interaction of users with a site to a lesser or greater degree. At its most developed, this involves a much greater degree of trust in users so that, for example, with a wiki the process of editing and contributing is much more decentralised.

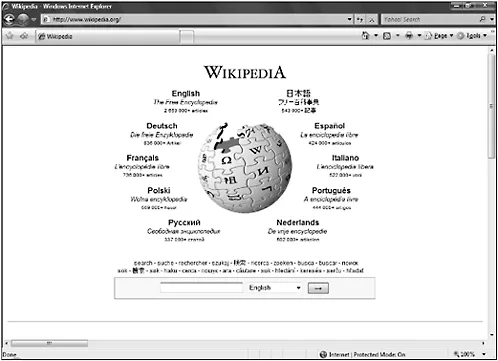

Wikipedia is one of the most remarkable Web 2.0 sites to have emerged in recent years.

O’Reilly has spoken of the ability of sites such as Wikipedia to ‘harness collective intelligence’, although a consequence of this letting go of centralised control makes it much easier for users to enter incorrect information accidentally or deliberately. An important outcome of this simple fact is that for this to function correctly, it depends upon a community of informed and interested users to constantly monitor and moderate activity.

Attwell and Elferink (2007: 2) point out:

the Architecture of Participation is not a software system as such—or even a collection of software tools—but rather a bringing together of various technologies and activities designed to facilitate and promote participation, communication and the active construction of meanings and knowledge.

Core to this is trust, that a site is not a ‘walled garden’ but something that should be as easy to enter and leave as possible (which in turn relates to issues of usability) and, to maintain this trust, that users’ data belongs to them. In turn, this has drawn attention to the relationship between sites that involve some form of social networking or communal activity and ownership of intellectual property, with trends established by the development of open-source software and the role of organisations such as the Creative Commons (creativecommons.org) being important in developing new attitudes towards copyright, drawing a middle line between anarchic piracy that damages trust and over-restrictive regulations that stifle innovation.

The social impact of these architectures of participation is already proving itself to be immensely important, for example in the rise of the blogosphere (which encapsulates the successes and irritations of much of Web 2.0 capabilities). The combination of community and architecture draws attention to the main capability of Web 2.0 development: technology provides the framework to exchange data (the architecture) that should be as simple and seamless as possible, but without a community of users to produce that data in the first place the technology itself is redundant.

Data as focus

Web 1.0 was as much about information as Web 2.0, but the means for distributing data has changed significantly. One important consequence of creating participative architectures has been the growth of user-generated content (UGC), or consumer-generated media, referring to publicly available content produced by end users rather than the producers or administrators of a site.

Flickr was one of the first sites to make sharing user content its core activity.

Often UGC is only part of a site but in some cases, as with Flickr or YouTube, it constitutes the entire process ...