CHAPTER ONE

Modeling Dyadic and Interdependent Data in Developmental Research: An Introduction

Noel A. Card

University of Arizona

Todd D. Little

James P. Selig

University of Kansas

Relationships with others play a critical role in child and adolescent development. Unfortunately, the use of analytic techniques that appropriately model dyadic and group interdependencies has not yet taken root in developmental research. Whereas we view these interdependencies as valuable information and an important focus for research, most researchers, unfortunately, often ignore or attempt to avoid interdependencies in their data. In our introduction to this volume, we emphasize the importance of interdependence in developmental science, highlight the need for specific analytic approaches for modeling interdependent data, and present the goals of this book.

Interdependence in Developmental Science

Psychology and many related fields have traditionally focused on individual differences. This focus has been useful in various ways, such as in helping to understand why some children are aggressive whereas others are not, why some adolescents are popular whereas others are unpopular, and why some adults exhibit certain personality traits whereas others exhibit quite different traits. Recently, however, there has been a shift in thinking beyond the individual to considering the relationship contexts in which much of human behavior occurs. For example, personality theorists (e.g., Cervone, 2004; Mischel & Shoda, 1995) have argued for moving away from the view of personality as a global set of qualities to viewing personality as a pattern of behaviors in different contexts, including different relationship contexts. Similarly, research on childhood aggression—traditionally considered in terms of individual differences in the amount of aggression enacted—can be better understood as a dyadic relationship between aggressors and victims (Card & Hodges, 2006; Pierce & Cohen, 1995). Even sexual orientation, which has long been considered as a quality of an individual, has been shown to exhibit fluidity across romantic relationships during emerging adulthood (Diamond, 2003).

Although consideration of the role of relationships in many fields is quite recent, developmental science can be applauded for its long-standing recognition of the interdependent nature of child and adolescent development. We know, for example, that development within the family context is a product of overall family environment, parent–child relationships, and sibling relationships. With age, children increasingly interact with peers. As a result, sociometric position, group norms for various behaviors, and dyadic relationships (both friendship and antipathetic) all have substantial influences on development. In short, developmental researchers have long recognized the importance of relationships, within both the family and the peer group, for understanding developmental processes.

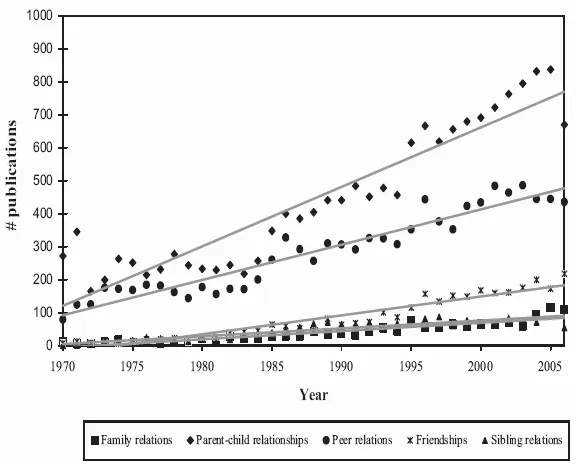

To illustrate this research activity, we performed a search of select descriptors of works indexed in PsycINFO. Although such a search is far from complete, we used the number of records in each year to provide a rough index of research activity on several topics in child and adolescent development. As shown in Figure 1.1, there has been an increasing amount of research on family relations, parent–child relationships, peer relations, friendships, and sibling relationships. It can also be seen that parent–child relationships and peer relations are highly active foci of research, with current rates between 300 and 800 reports per year. Studies on family relations, sibling relationships, and friendships are less common, but still represent active areas of research with approximately 50 to 150 reports published per year.

Although these topics represent only some of the relevant areas of study, these findings indicate the widespread—and increasing—interest of developmental researchers in aspects of development that are inherently interdependent in nature. In both the home and peer context, researchers have considered both group- and dyadic-level interdependencies. Specifically, various aspects of family systems (e.g., family conflict, negativity, support) can be analyzed in terms of interdependencies among different members of the family group (e.g., which family members are supportive of which other family

members). Consideration of the family context at the level of the dyad leads to consideration of marital, parent–child, and sibling relationships (as well as a range of other relationships, such as with extended family members). Similarly, the peer context can be considered at both the group (e.g., popularity and rejection, classroom norms) and dyadic (e.g., friendships, antipathetic relationships, romantic relationships) levels. Clearly, in both the family and peer context, when the level of analysis is either the group or the dyad, the interdependencies that exist among individuals provide valuable information and are thus important foci for research.

The Need for Analytic Approaches to Studying Interdependence

We have seen that developmental science has, as a field, long recognized the interdependent nature of child and adolescent development. Recognition of this importance has not, however, been matched by use of appropriate strategies for modeling these interdependencies. Traditionally, developmental science has relied on statistical techniques that assume independence of observations. If a researcher is studying individual characteristics of the child and samples a random group of children, then the use of traditional methods of analysis is perfectly acceptable because each observation is independent of one another—a key assumption of the traditional analytic methods. However, if a researcher is interested in friendships (for example), and some of these children in the sample are friends with one another, then traditional analytic methods are not appropriate because each observation (i.e., child) is not independent of other observations (i.e., peers) within the sample. Instead, the friendship child A has with child B makes these two children interdependent, both conceptually and statistically. In this instance, special data analytic techniques are needed.

Unfortunately, appropriate techniques for modeling these interdependent data have emerged slowly. Equally unfortunate is the fact that developmental researchers have been slow to employ the techniques that have been put forth. Two outcomes have resulted from this slow progress. First, developmental researchers too often rely on inappropriate analytic techniques that are likely to provide inaccurate answers, such as analyzing data from a sample of children as if they were independent cases (i.e., ignoring interdependence). Alternatively, researchers have attempted countless means to remove interdependence from their data, such as randomly selecting one member of a friendship pair for analysis (i.e., avoiding interdependence). The problem with either ignoring or avoiding interdependence is that it treats this interdependence as a nuisance. As outlined above, however, family relations, parent–child relationships, childhood friendships, and similar interdependencies are not nuisances to be avoided, but rather are critically important phenomena for investigation. The use of appropriate statistical models for interdependent developmental data will allow us to study these phenomena, as well as reveal novel questions that we have failed to see within our traditional analytic framework.

Why has this disconnect between data analyses (which assume independence) and foci of developmental research (which often assume interdependence) emerged? There are likely multiple causes, but we consider three interrelated possibilities here. First, the quantitative techniques of analyzing interdependent data have only slowly emerged. Although some brave quantitative researchers have ventured into this area, it is only in the last couple of decades (relatively short in the history of quantitative analysis) that systematic methods have been developed and evaluated (for a thorough overview, see Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). Second, the data analytic techniques that have been developed are not necessarily best suited to the needs of developmental research. One notable example of this point is that most techniques of interdependent data analysis have not been extended to incorporate longitudinal data. Third, we suspect that the increasing specialization of researchers in both quantitative and developmental sciences has resulted in a situation in which there is generally little communication across these areas. In other words, developmental researchers may not be aware of the techniques emerging from quantitative research, and quantitative researchers may not be aware of the unique opportunities and challenges of developmental applications of these techniques.

Goals of This Book

We believe that both developmental and quantitative researchers can benefit from dialogue across these two disciplines. To prompt such dialogue, we received funds from the National Science Foundation and the Society of Multivariate Experimental Psychology to hold a conference at the University of Kansas, attended by the authors of chapters in this book. We selected both developmental and quantitative researchers to come together to discuss the unique opportunities and challenges of modeling interdependent developmental data. The first goal of the current book is to share the product of this discussion. As we hope you agree, this dialogue between developmental and quantitative experts has resulted in substantial advances for each discipline and in identifying much common interest, both of which are represented in the chapters of this book.

The second goal of this book is to describe techniques for analyzing interdependent developmental data. The chapters of this book provide clear descriptions of various techniques for analyzing data from dyads and small groups, including the actor–partner interdependence model (Laursen, Popp, Burk, Kerr, & Stattin, chapter 2), the mutual influence model (Sadler & Woody, chapter 7), dyadic models of co-occurring change (Ferrer & Widaman, chapter 6; Kashy & Donnellan, chapter 8; Ram & Pedersen, chapter 5; Selig, McNamara, Card, & Little, chapter 9), triadic models (Bond & Cross, chapter 16), the social relations model (Branje, Finkenauer, & Meeus, chapter 12; Card, Little, & Selig, chapter 11; Cook, chapter 3; Malloy & Cillessen, chapter 10), and various aspects of social network analysis (Cillessen & Borch, chapter 4; Kindermann, chapter 14; Laursen, Popp, Burk, Kerr, & Stattin, chapter 2; Templin, chapter 13; Zijlstra, Veenstra, & Van Duijn, chapter 15). The analytic approaches being developed in these areas involve many topics of active quantitative research, making it difficult for most of us to keep abreast of current best practices. We are pleased that many of the originators and most active innovators of these techniques have provided clear and comprehensive descriptions of the methods, opportunities, and limitations of these techniques in the chapters that follow (see especially the concluding chapter by Kenny, chapter 17).

The third goal is to demonstrate the substantive opportunities of sophisticated techniques of interdependent data analysis. In other words, we did not want to only describe the various techniques of analyzing interdependent data; instead, we challenged the authors to lead by example, and to show the uni...