![]()

Chapter 1

The Problem

What are we to make of the following, rather obscure, anecdote from the life of Abraham Lincoln? In 1854, a Whig Party activist loyal to Lincoln placed a declaration of the budding politician's candidacy for state legislature in the local newspaper. However, Lincoln did not want to run for the legislature because he had his eye on a U.S. Senate seat and sitting legislators could not, under Illinois law, be considered by the legislature for a Senate seat. Lincoln was extremely unhappy about this public declaration of his candidacy. One observer described him as “the saddest man I Ever Saw—the gloomiest: he walked up and down . . . almost crying.”1 But he now faced a choice. He could either bow out of the state legislative race and appear disloyal to his party (which he would need if he were to have a shot at becoming a U.S. senator) or he could run for the legislature knowing full well that he would not take office if he won. Can we guess which option “Honest Abe” chose? Perhaps surprisingly, he chose the latter course and refused to take his seat after the election. Doing so, according to Lincoln biographer Richard Carwardine, was “an action which appeared to put self before cause and did his reputation some harm amongst radical antislavery men.”2

The moral of the story might be that even our greatest political heroes are human beings who were forced at various points in their careers to make difficult decisions and who sometimes behaved in less than admirable ways. Or we could conclude that behind every great statesman is a great politician. Indeed, as Chester Maxey noted of Lincoln in his 1948 essay “A Plea for the Politician”:

Lincoln is all statesman now; it is almost a sacrilege to suggest the contrary. The scheming, contriving, manipulating frontier politician who outsmarted the best of them has faded into oblivion, and we have instead an alabaster saint who never could have done what Lincoln did because he would not have played politics with Lincoln's calculating cleverness.3

I suspect, however, that what most Americans will take from such a story is that all politicians are the same, whether we build monuments to them or not. They are opportunistic and overly ambitious. And, in the end, all politicians are in it only for themselves.

This book seeks to understand why Americans dislike politicians so intensely—and argues that they're wrong to do so. Ultimately, no form of democracy can function without trust in others. In a direct democracy, the populace would have to trust their fellow citizens to be informed enough to contribute meaningfully to a collective consideration of public policy and to balance their own interests against the public interest. But in a representative democracy, citizens must trust politicians to not only represent their constituents’ interests, but to do what they think is best for their districts, their states, and the nation. Unfortunately, as we'll soon see, Americans have very little trust in politicians, and a great deal of disdain for them.

This chapter establishes the problem to be addressed in the book, namely, the widespread anti-politician sentiment that exists in the United States today. I begin by exploring the ample evidence of the public's contempt for politicians. I then examine a set of contradictory expectations we hold of our politicians—or what I'll call the “expectations trap”—that will help structure the rest of the book. Finally, I introduce the argument that our disregard for politicians is not only unfair, but has the potential to damage our democracy.

The Evidence

The claim that Americans dislike politicians seems self-evident and, as such, hardly needs empirical evidence to confirm it. Nevertheless, the evidence is abundant; and it is instructive. For instance, Gallup has asked about the honesty and ethical standards of those in different occupations since 1976. In 2007, Gallup asked respondents about 22 professions. Nurses ranked first, with 83 percent of the respondents saying that their honesty and ethical standards were “very high” or “high.” State office holders and Members of Congress, however, ranked near the bottom of the list, with only 12 and 9 percent, respectively, saying that they had very high or high levels of honesty and ethical standards. Only advertising practitioners (6 percent), car salesmen (5 percent), and lobbyists (5 percent) ranked lower.4

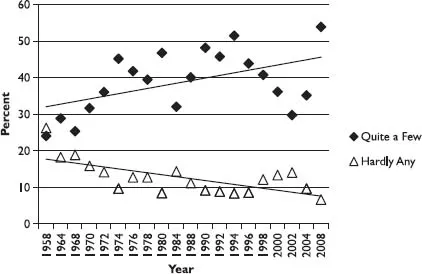

On a fairly regular basis since 1958, the American National Election Study has asked respondents whether quite a few, not very many, or hardly any of those running the government are “crooked.” In 2008, more people than ever (53.9 percent) believed that quite a few government officials were crooked and fewer than ever (6.7 percent) thought hardly any were.5 These numbers are similar to the results Gallup found in January 2008 when that organization asked the same question. However, in addition to the 52 percent of Gallup respondents who said quite a few of those running government are crooked, another 5 percent volunteered (that is, without being offered such a choice) that all of them are crooked.6 Figure 1.1 shows the trends over time in the NES survey. Obviously, the number of people who believe that government is being run, in large measure, by crooks has increased dramatically over the last 50 years.

Figure 1.1 Percent of Respondents Who Think There are “Quite a Few” or “Hardly Any” Crooks Running the Government, 1958–2008.

Source: American National Election Study 1948– 2004 – Cumulative and American National Election Study 2008; Survey Documentation and Analysis, University of California, Berkeley, http://sda.berkeley.edu/archive.htm (accessed July 25, 2010).

John Hibbing and Elizabeth Theiss-Morse have studied the public's attitudes toward American political institutions more than any other political scientists. In the mid 1990s, they conducted a series of surveys and focus groups to probe people's perceptions of various aspects of the political system. “Focus-group participants,” according to Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, “were obviously highly dissatisfied with politicians in general and quickly drew upon their ‘politician’ stereotype—politicians are dishonest and self-centered.”7 Some participants considered all politicians liars and many believed that politicians live by a double standard; while they make laws for the rest of us, they act as though they are above the law.

In a subsequent study, Hibbing and Theiss-Morse found that Americans are highly distrustful of politicians and find them “fractious and greedy.”8 At the same time, the public found elected officials to be more intelligent and far more informed than ordinary Americans. In fact, when Hibbing and Theiss-Morse scratched the surface of survey results by conducting additional focus groups, they found the participants to “believe that [ordinary] people aren't very bright, they don't care, they are lazy, they are selfish, they want to be left alone, and they don't want to be informed.”9 The disdain for politicians is so great, however, that despite the public's unflattering view of itself, people would prefer “to shift power from institutions and elected officials toward ordinary Americans.”10

Of course, many people can point to particular politicians they are fond of and even admire. It has long been recognized, for example, that Americans tend to like their own member of Congress but dislike the rest of Congress. Far from challenging the claim that people hate politicians, this fact bolsters it. As Hibbing and Theiss-Morse have shown, when people think about Congress, they think of the members of Congress and not an abstract institution.11 Since members of Congress are politicians, people consistently give “Congress” low marks. The fact that people may like their own member more then the rest of them means only that they are able to view their own representative as an actual person.12 In general, however, people treat politicians as caricatures.

Less quantifiable than public opinion, but every bit as damning, is the evidence from popular culture. Anti-politician sentiment is ubiquitous on late-night television talk shows like The Tonight Show with Jay Leno or The Late Show with David Letterman, satirical news programs such as The Daily Show with Jon Stewart and The Colbert Report, and sketch comedy shows like Saturday Night Live. Politicians regularly serve as fodder for comics, who exploit their foibles for audiences that seem never to tire of what is essentially the same routine night after night—a politician says or does something foolish and the comedian is there with a clever punchline to expose the stupidity. Though the jokes may be targeted at individual politicians, the steady drumbeat of ridicule marks them all as ignorant, hypocritical, manipulative, and/or dishonest.

Indeed, scholars have shown that the topical comedy of late-night shows generates negative attitudes about politicians, not to mention the political system generally. Political scientists Jody Baumgartner and Jonathan Morris designed an experiment in which subjects watched video taken from either The Daily Show with Jon Stewart or the CBS Evening News (a control group watched no video). The video clips reflected each show's treatment of the major party presidential candidates in 2004 (i.e., George W. Bush and John F. Kerry). The results of the experiment revealed that The Daily Show significantly lowered its viewers’ evaluations of the candidates while watching the news had no effect on the subjects’ evaluations. Daily Show viewers also reported significantly less faith in the electoral system, less trust in the news media's ability to report fairly and accurately, and a lower overall evaluation of the media's coverage of politics after watching the program; there was no significant change in the responses to these items by those who watched the news.13

Baumgartner and Morris's experiment is, of course, just one study. But their findings give empirical weight to the speculative conclusions of many observers of late-night comedy. Roderick Hart and Johanna Hartelius, for instance, accuse Jon Stewart of engaging in “unbridled political cynicism,” arguing that he “does not stimulate a polis to have new and productive thoughts; like his ancient predecessors [the Cynics], he merely produces inertia.”14 The same could be said of all late-night comics. “Late-night's anti-political jokes,” writes Russell Peterson, “declare the entire system—from voting to legislating to governing—an irredeemable sham.” These jokes are, in other words, “implicitly anti-democratic.”15

To be fair, some movies and television dramas take a nuanced view of politicians. The West Wing, for example, depicted fictional President Jed Bartlett as an honest and dedicated public servant. But for every President Bartlett, there are dozens of corrupt or buffoonish fictional politicians who serve as one-dimensional symbols of a profession that everyone recognizes as sleazy.

Slogans and humorous sayings that express contempt for politicians are routinely on display on t-shirts and bumper stickers. On one relatively popular bumper sticker, politicians are said to be like diapers— “they have to be changed, regularly and for the same reason.” The disdain for politicians is also conveyed in the very use of the term itself. “Politician” is never a title that carries a positive connotation. If you doubt this, ask friends or co-workers to describe what they think of when they hear the term “politician.” You are not likely to hear one positive word in one hundred. In common parlance, “politician” is inevitably used as a synonym for “liar,” “cheater,” or “schemer.”

Perhaps the problem, then, is simply one of semantics. “Politician” may have become so freighted with negative symbolism that the word itself, and not the people it is used to describe, generates bad feelings. To test whether an alternative label would illicit more positive attitudes, I designed a split ballot experiment for a national survey conducted by the Center for Opinion Research at Franklin & Marshall College in February 2010. Half the sample was asked to choose between contrary descriptions of “elected officials” and the other half was asked about “politicians.”

The responses to our questions, reported in Table 1.1, clearly indicate that people have as much contempt for “elected officials” as they do for “politicians.” For example, 60 percent of the respondents think elected officials are dishonest but only slightly more (65 percent) chose the same descriptor for politicians. When asked whether elected officials/politicians are more interested in solving public problems or winning elections, 84 percent said winning elections is more important to elected officials while 86 percent said the same of politicians. And while 75 percent think elected officials do what's popular, as opposed to what's right, 77 percent think politicians do the same. There is, then, little difference between “elected officials” and “politicians” from the public's perspective.16

Of course, politicians themselves contribute to the dismal view of politicians. Leave aside the intensely negative campaigns that nearly all candidates engage in and that undoubtedly take a toll on the reputations of all politicians (since most of them are the targets of negative attacks at one time or another). Think of how often candidates proclaim, “I am not a poli...