![]()

Chapter 1

Introductions

Neil Croally and Roy Hyde

Glossary items: aulos, aulētris; dithyramb; elegiac couplet; epinikian; hexameter; iambic trimeter; monody; pentameter; polis; stichic metres; strophic metres.

Classical authors tended to work within literary traditions; they also produced their work in a cultural context that retained many similar features, both over the wide geographical area covered by the Graeco-Roman world and also through the many centuries in which Graeco-Roman culture dominated the Mediterranean. For that reason, and because we wish to avoid repetition, we have included in this introductory chapter a number of the aforementioned features. They are arranged alphabetically, and reminders of their presence here in this opening chapter will be made in the following chapters.

Greek dialects

The English spoken today by a native of London may sound very different to that spoken by, for example, a New Yorker, an Australian or a Glaswegian, though each of them will – more or less, and perhaps with some effort – be able to make sense of what the other says. Ancient Greek, too, showed considerable regional variations, with the important difference for us (as readers, rather than speakers, of the language) that, while English for the most part follows a standard system of spelling, in Greek, variations were written as well as pronounced. Thus, where an Athenian would say (and write, if he could write) theoi when referring to ‘the gods’, a Spartan would say sioi; to a Spartan, amera was the day, selana the moon: an Athenian would have said hēmera and selēnē, and so on.

Scholars classify the dialects of Ancient Greek under five major headings: Attic-Ionic, spoken in Attica and those Aegean islands and parts of the coast that had been colonized by Ionian Greeks; Doric, in the Peloponnese and Dorian colonies; Aeolic, in Thessaly, Boeotia, and some eastern settlements such as Lesbos; Arcado-Cypriot, in Arcadia in the Peloponnese and Cyprus; and North-West Greek, in the northern and western parts of mainland Greece. (North-West Greek and Doric are sometimes treated as varieties of West Greek.) The dialect ‘map’ of Greece, then, is complicated by the mobility of the Greeks around the Mediterranean, and by their colonizing activities. As far as literature is concerned, it is further complicated by the tendency of particular dialects, or mixtures of them, to become associated with particular literary genres. Thus, the dialect of the Iliad and the Odyssey, which is essentially Ionic with some Aeolic and Arcado-Cypriot colouring, becomes the language of epic poetry: so that the epic poet Apollonius, who came from Rhodes and worked in Alexandria, several centuries after Homer, still writes his Argonautica in recognizably Homeric Greek; and, for that matter, more than a thousand years after Homer, the Christian Egyptian epic poet Nonnus could write about the pagan god Dionysus in Homeric Greek (see 12g). Literary tradition was stronger than regional boundaries: in Athens, the iambic sections of tragedies (the parts spoken by the actors) were conventionally written in Homerically influenced Attic, while those parts sung by the choruses were in the traditional Doric-influenced language used in choral lyric poetry (see ‘Metre, music, genre’ in this chapter).

Literary dialects, then, like the writers themselves, crossed regional boundaries, and outlasted whatever origins they had had in the speech of everyday life. The use of local dialects was also undermined by the spread of the koinē (from koinē dialektos – ‘common speech’), which derived from the classical Attic Greek that most of us begin by learning, and spread through the near east, first as a result of the increase of Athenian influence from the fifth century BCE onwards, and later – and more widely – as a result of Philip of Macedon’s adoption of Attic Greek as the language of the Macedonian court and the subsequent conquests of his son Alexander the Great. No doubt the ordinary Greek in Laconia or Boeotia continued to speak the dialect his fathers and grandfathers had spoken: but even when the eastern Mediterranean came under Roman control, the koinē remained its language of administration and of commerce, and eventually became the bureaucratic language of the Byzantine empire which survived until 1453 CE.

Further reading

Buck (1998; 2009); Horrocks (1997).

Literacy

The Mycenaeans were literate, but their cumbersome Linear B script seems to have been used only for limited administrative purposes, and there is no indication that it was used to write down ‘literature’, or that any significant proportion of the population could read or write. After the Mycenaeans, there is no sign of writing in Greece until the eighth century BCE, and at first it seems to have been used to indicate ownership of objects (e.g. names written on pots), and for religious purposes such as dedications or curses. The new Greek alphabet was derived from that of the Phoenicians, with the refinement that symbols were now used to indicate vowels, which was not the case for Phoenician (or for Linear B).

Books (probably papyrus rolls) existed in the sixth century BCE, if not before. Hesiod, around 700, may have used writing to preserve his poems (though this does not mean that he himself could write: his technique is essentially that of an oral poet), and the Homeric poems were probably written down about the same time. In the sixth century, Peisistratus, tyrant of Athens, had the Iliad and the Odyssey written down, in order to try to establish a definitive text. By about 500, book-rolls were being used for educational purposes, though – like writing materials – they continued to be expensive throughout antiquity, and few people owned many.

Early literature is in verse, as verse is easier to remember. The advent of writing was thus of vital importance to the development of prose as a means of recording and communicating ideas in the fifth century BCE, and in the wider and quicker dissemination of knowledge and theory. But memorization of texts remained central to Greek educational methods, because books continued to be relatively rare, expensive to produce, and difficult to read, as punctuation was largely unknown. Book-rolls were also hard to consult, so that authors frequently misquote each other through relying on memory. Oral performance continued to be central not only for verse, but also for prose texts, and literature was aurally received, rather than read on the page, by most people.

It has been estimated that the level of literacy never rose above 20–30 per cent in ancient Greece (Harris, 1989). But literacy does not only mean the ability to read books: perhaps few people were ever able to read long complex texts easily, and fewer still to write them. But far more were probably able to read simple notices or inscriptions, or to write their names, if little more. In Athens in the late fifth century, for example, public inscriptions of all kinds, including laws, proliferated, and this must have encouraged people to learn to read at least a little, if not to write.

There is no firm evidence for oral poetry at Rome: from the beginning, Latin literature – frequently translated or adapted from Greek – seems to have been written down. This does not necessarily mean that it was always read; throughout Rome’s history most ‘literature’ was probably first aurally received, through the widespread practice of recitationes, readings of an author’s work to an invited audience. Education, and consequently literacy, were prized by the wealthier classes, which does not, of course, provide evidence for the population at large, whose experience remains, as usual, mostly obscure. On the other hand, archaeological evidence, such as graffiti at Pompeii, papyri from Egypt, and the writing-tablets from Vindolanda on Hadrian’s Wall, testify to some degree of more widespread literacy, not least amongst soldiers. The extent of the later empire makes generalization impossible: levels of literacy were no doubt lower in rural areas than in cities, but Varro (first century CE) recommends that even an estate-owner’s head shepherd (who would be a slave) should have some degree of literacy.

It is important to remember, in an age when the ability to read and write is frequently equated with intelligence and civilization, and when most of us get our information and pass it on in written form, that a non-literate society, or one in which literacy levels are low, is not necessarily a backward one. Non-literate societies manage to remember and to disseminate large amounts of complex information successfully. Writing and reading facilitate the spread and exchange of information and ideas, but do not necessarily improve their quality.

Further reading

Bowman and Woolf (1994); Harris (1989); Havelock (1982); Thomas (1992). On literacy and democracy in classical Athens, see now Missiou (2010).

Metre, music, genre

The metres of Greek and Latin poetry (unlike conventional English poetry) are based not on which syllable of a word is stressed, but on the length of syllables: thus, for example, diphthongs (two vowels pronounced as one, such as ai in Greek or ae in Latin) make a syllable long, whereas a syllable with a single vowel may be long (for example, a as in ‘father’) or short (a in ‘fat’) depending on how it is pronounced.

Metres come in two basic kinds: stichic metres are composed in recurring lines of the same type, such as the hexameters of Homer and Virgil, or the iambic trimeters of Attic tragedy; a variation on this is the elegiac couplet, consisting of one hexameter followed always by one pentameter. Strophic metres are composed in stanzas, in one of two basic forms: the typical monodic lyric poem (of, for example, many of the poems of Sappho, Alcaeus and Anacreon) is in stanzas all of the same form; choral lyric poetry (such as that of Alcman or the choral odes in Attic tragedy; and Pindar’s odes, which may or may not have been chorally performed) are triadic, consisting of a pair of stanzas each in the same metrical form followed by a third in a related but not identical form.

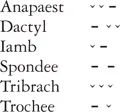

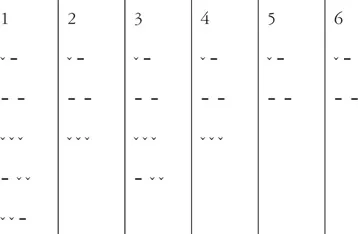

Some common metrical feet (ˇ = short; - = long)

The shortness or length of a syllable in Greek and Latin verse is a matter of how long it would take to pronounce the syllable. Classical metres were not based on stress, as those of English verse are. Long syllables could be either:

1 those that include a naturally long vowel, such as an omega in Greek, or a diphthong (two vowels put together to form one sound, such as – ae in Latin), or

2 those in which a vowel is followed by two consonants, whether those consonants are part of the same word as the preceding vowel or not. Below are listed some of the common units (or feet) of classical metres.

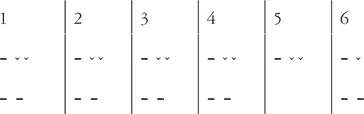

Some common metrical schemes

| Hexameter | The metre most famously of epic poetry, made up of six feet and dominated by the dactyl. |

| | |

So variation is allowed in the first four feet, and in the last syllable. It is certainly not normal to have a spondee in the fifth foot (Virgil has such a fifth foot rarely, though it is more common in, for example, Catullus 64). Normally, the caesura – a natural break in the line – comes either after the first syllable of the third foot or after the first syllable of the fourth foot (normally the former).

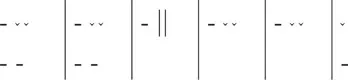

| Elegiac couplet | The first line of the couplet is as the hexameter above; the second is as follows: |

| | |

Little variation is allowed here, though Alexandrian poetry is less rigidly tied to the scheme than Ovid.

| Iambic trimeter | This metre is made of three metra, with each metron consisting of two feet. This is the metre of much of Greek tragedy; there seems to have been more variation in later tragedies. |

| | |

The caesura is again after the first syllable of the third or fourth foot.

In Greece, poetry and music were originally intimately connected: almost all poetry had some kind of musical accompaniment, except the iambic sections of drama and obvious cases such as funerary epigram. But, with the increase in literacy and the tendency of poets to write rather than compose with music in mind (and the rise of the reader in addition to the listener), the importance of music declined. The Romans in general took over Greek metrical forms, except for the (probably) native Saturnian metre in which some early poetry was written but which rapidly disappeared under Greek influence, although the musical element was lacking: music was an important element in Greek education, as it was not at Rome; most educated Greeks had some musical competence, whereas upper-class Romans tended to look down on musicians. As far as we know, Horace’s Centennial Hymn (Carmen Saeculare) was the only Latin poem which was intended to be sung. And the emperor Nero, for example, who liked to sing and play the lyre in public, was generally vilified, not because he was bad at it but because he did it at all.

The instruments most frequently played were various forms of the lyre, a stringed instrument somewhat like a small harp (and played like one, by plucking the strings), though its size and the number of strings varied. Lyric poems, both monodic and choral, were sung to lyre accompaniment, and sometimes to that of the aulos as well. This was not a flute, as the word is often wrongly translated, but more like an oboe; auloi were often played in pairs by the same player. This suggests that harmony might have been possible, but in fact it seems that for the most part instruments, and voices with instrumental accompaniment, played and sang in unison. Other instruments were known, but not much used in ordinary music-making: trumpets, for example, were usually used only in military contexts for giving signals, though the Romans used them at funerals, and percussion instruments of various kinds were used, often in a religious context. But music was not a static art. The organ, at first powered by water and later by air pressure, and recognizably the ancestor of the modern organ, was invented in Alexandria in the third century BCE, and became quite popular, especially with the unmusical Romans, who are said to have liked it because it made plenty of noise.

Fashions in music, of course, changed too. Towards the end of the fourth century BCE, for example, ‘new music’ became popular and controversial (it was criticized on moral as well as aesthetic grounds by conservatives, as innovations in the arts so often are). The basis of Greek music was the mode: modern western musical scales can begin on any note, and the intervals between notes in any scale are the same (depending on whether it is major or minor); the various Greek modes (harmoniai) each consisted of a different sequence of intervals, and generally a composition was played and sung wholly in the same mode (lyres presumably had to be tuned to a particular mode). One of the innovations of the new musicians appears to have been modulation between modes; harmonic experimentation may also have been involved – it is hard to imagine that Timotheus, for example, the great virtuoso of the new music, would have been satisfied with mere unison of voice and accompaniment. We do not have any of his music, but a substantial part of the text of one of his dithyrambs survives, and if the music matched the words (highly ornate: excessively so, in some opinions), he must have been doing some quite remarkable things.

No doubt, though, the ordinary individual with a basic musical education continued to play and sing much as his father and grandfather had. Conservatism also characterizes the Greek and (without the musical element) Roman attitude to metre, music and genre. That is, for most of antiquity, particular metres continued to be associated with particular literary genres, because the earliest examples of them used that metre. The metre of epic poetry, for example, was established as the hexameter by the precedent of Homer, and remained fixed. Though the Homeric bard sang, or chanted, to the accompaniment of the lyre, it is unlikely that Apollonius of Rhodes, for example, did so – and Roman epic poets certainly did not, though they retained the metre. In Greece, dialects too were associated with particular genres: the basically Ionic dialect used by Homer continued to be the dialect of epic, regardless of the poet’s native dialect. Similarly, the dialect of triadic lyric song was traditionally (basically) Doric, and it clearly appeared natural enough to the audience at an Athenian tragedy that the actors spoke Attic while the Chorus, when it sang, sang in Doric.

Further reading

On ancient Greek music, see Hagel (2009); West (1994). On Greek metre, see West (1987); on Latin metre, see Raven (1965).

The Olympic and other games

The Olympic Games, held at Olympia in the north-west Peloponnese, like the three other major Greek games, the Pythian (at Delphi), the Nemean (at Nemea in the north-east Peloponnese, and the Isthmian (at Corinth) were a religious festival, not simply a sp...