- 876 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The first in a new series of five books describing and illustrating the seminal architectural traditions of the world, Antiquity traces architectural history from its very beginnings until the time when the traditions that shape today's environments began to flourish.

More than a catalogue of buildings, in this work Tadgell provides their political, technological, social and cultural contexts and explores architecture, not only as the development of form and space but as an expression of the civilization within which it evolves. The buildings are analyzed and illustrated with over 1200 colour photographs and 400 drawings while the societies that produced them are brought to life through a broad selection of their artefacts.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Antiquity by Christopher Tadgell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architettura & Architettura generale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArchitetturaSubtopic

Architettura generalePart 1 West Asia and the Eastern Mediterranean

›1.11 (PAGES 22–27) THE EUPHRATES VALLEY AT HALABIYA.

1.1 The Fertile Crescent and the Nile Valley

›1.12 THE NILE VALLEY WITH SAQQARA IN THE DISTANCE.

Introduction: Civilization and Architecture

Civilization first developed on the rich alluvial plain of lower Mesopotamia, where the flood came inopportunely in spring - to the disadvantage of sowing rather than to the advantage of growing - but water-borne transport facilitated communication, trade and the accumulation of wealth. It was marked by the organization of society on territorial rather than kinship lines and the emergence of an elite capable of promoting territorial, rather than local, public works. It depended on the progressively adroit exploitation of nature, the ordered deployment of resources and the escalation of population growth as agriculture spread with channelled water from restricted riverbank to expansive plain. As the harnessing of wind and water - no less than animals - propelled diverse people to migration and commerce, it was enriched through cross-fertilization issuing from emulation and impoverished in war born of envy.

City was ever to fight city but even more fundamental was the clash between citizen and nomad. Indeed, it must have been the primal need to order the defence of the village from marauders and their chief that prompted the emergence of the civic potentate. Essentially urban, under that potentate civilization entailed social differentation, the fostering of crafts among the increasing numbers freed from involvement in growing food, the invention of writing, mathematics and time-keeping, the standardization of language, beliefs and law, the efflorescence of religion and the construction of great buildings to enshrine the gods.

A starting point for architecture is naturally elusive in the slow process of evolution after the mud loaf had become the rectangular brick, the tent-like hut was superseded by the house of rectangular rooms and the shrine

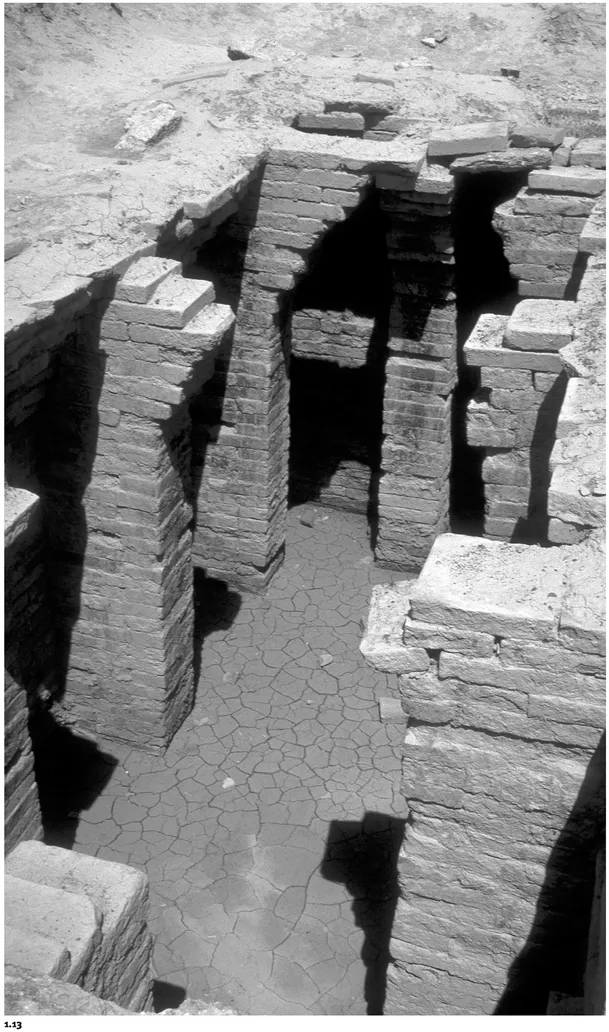

›1.13 MARI: brick tombs with walls and corbelled arches, early 2nd millennium.

1.14 ›1.14 KARNAK, GREAT TEMPLE OF AMUN: pillars in the Hall of Annals of Thutmosis III (1479–1425). The stylized lotus and papyrus represent Upper and Lower Egypt respectively.

achieved special identity. But it was in the conception of the shrine, at the service of religion, at the instigation of the priest – society’s first specialized practitioner to claim independence from the food production chain and sustenance from others – that building first flourishes as architecture. Moreover, in the art of building – religious or secular – similar conceptions were dictated by local conditions independently in several parts of the world at various times. These reveal a fundamental dichotomy: the contrasting principles are articulated primarily in the traditions of Egypt and Mesopotamia as they developed in the first half of the 3rd millennium BCE to accommodate their different ideals in enduring monuments.

The differing climatic, geological and topographical conditions of these two areas gave dominance in each to one of two basic building materials: mud brick (in Mesopotamia), and timber or reeds (in Egypt).1.11, 1.12 These, in turn, dictated the basic structural systems: wall and arch (arcuated), and post and beam (trabeated).1.13, 1.14 And these alternative types of structure naturally promoted two basic approaches to design, to the conception of the ordering of space: the informal or organic and the formal or rational with symmetry about a central axis. These two seminal traditions also assert the significance of form: pragmatic on the one hand, symbolic or representational on the other – that is, governed by the practical requirements of function, structure and situation or going beyond these to convey some special idea. Finally, they demonstrate the operation of patronage and ideology – the way a patron’s idea of his or her role in the established order informs the meaning of a building.

Materials and Structure

The land of the Tigris and Euphrates seems to have been treeless well before history. The spring flood was generally not constrained by cliffs that would have limited the extent of inundation and maximized its impact. Thus the main impression is not of a rich green strip but of mud baked hard in the sun. From these conditions came the most elemental of building materials: mud, compacted with straw or dung for binding, and sun-dried to form bricks which, piled one upon the other, form walls.1.13 It was soon seen that these needed protection from the weather. Baking in a kiln was developed for durability – not always for all the bricks needed for a vast walled complex, but at least for an outer skin in lieu of stone. And a malleable material like mud or clay invites moulding or the incision of a pattern – inevitably, in agrarian communities, a free-ranging, fantastic, even symbolic elaboration of motifs drawn from nature. Hence the revetment would be protective but also decorative and often didactic.1.17

In the Nile valley, on the other hand, the narrow floodplain, bordered not far from the river by sandstone cliffs, produced plenty of reeds which could be bound together to form posts, or woven into screens. It also supported groves of palms, producing softwood and fronds, easily worked or bound together for use in light structures. The palm and the reed bundle were alternative models: in each, the contact of load and support was celebrated with a frond-, flower- or bud-shaped capital. Groves of trees were cultivated for the food they gave and, as a source of bounty, were associated with the abode of god: they were seen as sacred. They were as important for the inspiration of form as for the provision of materials: in form as well as substance, as the tree became the column so the grove became the hall.1.14, 1.15

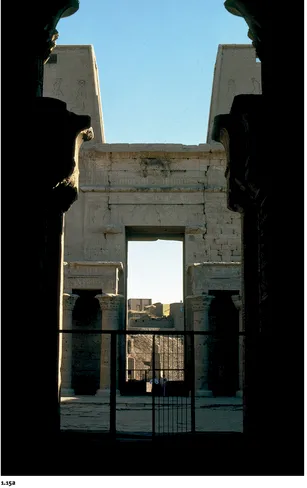

The Egyptians tell us – for instance, on the walls of the Temple of Horus at Edfu – that the temple is the island of the creator: if the plants of the Nile mudflats are recalled in its structure, in the sacred grove is to be found the origin of its hall of many columns. Hardwood, imported by sea from Lebanon in particular, supplanted the inadequate local product in major buildings when transportation and trade were sufficiently developed, and masonry had been introduced by the end of the 4th millennium. Of course, the Egyptians had plenty of mud for bricks too, and – unlike the Lower Mesopotamians – plenty of stone to complement it in constructing walls and entrance pylons to protect their sacred groves. And the floriate capital of the lotus type was extended across the top of walls as the concave coved cornice, one of the most characteristic features of Egyptian architecture.1.15, 1.16

›1.15 EDFU, TEMPLE OF HORUS, c. 250–116: (a) view along the main axis from the hypostyle hall, through the forecourt to the entrance between the twin pylons, (b) detail of columns and beams in the hypostyle hall at the head of the inner court.

In this typical Ptolemaic Egyptian cult temple, the six columns of the hall façade, screened to half-height, and the twelve larger interior columns have a variety of capitals ranging from the traditional palm-frond bundle (background) to variations on the lotus theme (foreground).

In this typical Ptolemaic Egyptian cult temple, the six columns of the hall façade, screened to half-height, and the twelve larger interior columns have a variety of capitals ranging from the traditional palm-frond bundle (background) to variations on the lotus theme (foreground).

Columns present no impediment to the flow of space, but walls must be breached. Masonry is durable under compression, vulnerable in tension – hence a flat lintel is weaker in the centre and must be massive to last.1.15 An opening in a wall may be corbelled: the masonry is laid in horizontal courses, each projecting beyond the one below from a certain level until they bridge the gap.1.13 However,

›1.16 (PAGES 30–31) PHILAE, TEMPLE OF ISIS: begun mid-3rd century and representing a late contracted example.

›1.17 (PAGES 32–37) BABYLON, ISHTAR GATE: reconstructed façade, c. 600 (Berlin, Museum of the Near East).

This was the north gate of Babylon, rebuilt under Nebuchadnezzar II following the destruction of the city by the Assyrians in 689. Next to the palace, it guarded the opening of the main axis of the town. Named after the goddess of war, Ishtar, the gate was embellished with animals sacred to her and to the city’s principal deity, Marduk. The circular flower (rosette) in the dado is ubiquitous.

This was the north gate of Babylon, rebuilt under Nebuchadnezzar II following the destruction of the city by the Assyrians in 689. Next to the palace, it guarded the opening of the main axis of the town. Named after the goddess of war, Ishtar, the gate was embellished with animals sacred to her and to the city’s principal deity, Marduk. The circular flower (rosette) in the dado is ubiquitous.

the soundest way of su...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- PROLOGUE: ORIGINS

- PART 1 WEST ASIA AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

- PART 2 PRE-COLUMBIAN AMERICA

- PART 3 THE CLASSICAL WORLD

- PART 4 CHRISTIANITY AND EMPIRE

- GLOSSARY

- FURTHER READING

- INDEX