- 170 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

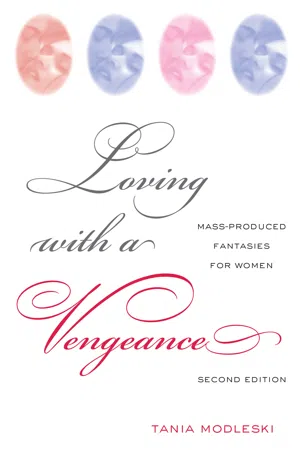

Upon its first publication, Loving with a Vengeance was a groundbreaking study of women readers and their relationship to mass-market romance fiction. Feminist scholar and cultural critic Tania Modleski has revisited her widely read book, bringing to this new edition a review of the issues that have, in the intervening years, shaped and reshaped questions of women's reading. With her trademark acuity and understanding of the power both of the mass-produced object, film, television, or popular literature, and the complex workings of reading and reception, she offers here a framework for thinking about one of popular culture's central issues.

This edition includes a new introduction, a new chapter, and changes throughout the existing text.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Loving with a Vengeance by Tania Modleski in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Media Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

MASS-PRODUCED FANTASIES FOR WOMEN

I

Although Harlequin Romances, Gothic novels, and soap operas provide mass(ive) entertainment for countless numbers of women of varying ages, classes, and even educational backgrounds, very few critics have taken them seriously enough to study them in any detail. The double critical standard, which feminists have claimed biases literary studies, is operative in the realm of mass-culture studies as well. One cannot find any writings on popular feminine narratives to match the aggrandized titles of certain classic studies of popular male genres (“The Gangster as Tragic Hero”) or the inflated claims made for, say, the detective novel which fill the pages of the Journal of Popular Culture. At a time when courses on popular culture have become semirespectable curricular offerings in colleges and universities, one is often hard put to find listed on the syllabi a single novel, film, or television program which makes its appeal primarily to women. As Virginia Woolf observed some time ago, “Speaking crudely, football and sport are ‘important’; the worship of fashion, the buying of clothes ‘trivial.’ And these values are inevitably transferred from life to fiction”—to popular fiction no less than to the fiction in the “great tradition.”1

However, this is not to advocate that criticism of female popular culture should simply “plug into” categories used in studies of male popular culture, categories which are themselves often secondhand, having been borrowed from “high culture” criticism in an effort to gain respectability. Such a task would be impossible even were it desirable. As Joanna Russ has argued, the positive cultural myths are mostly male ones; role reversal (for example, “The Scheming Little Adventuress as Tragic Hero”) is an impossibility, involving a contradiction in terms.2

There re no doubt a number of reasons why female protagonists and female popular fiction cannot claim for themselves the kind of status male heroes and male texts so often claim. This kind of aggrandizement, occurring both in fiction and in criticism, would appear to be a masculine mode, traceable, at least in part, to the male oedipal conflict. This conflict, it is important to note, is resolved at the expense of woman and necessitates her devaluation. For the male gains access to culture and the symbolic first by perceiving the “lack” of the once all-powerful mother and then by identifying with the “superior” male, the father. Recently, critics, following Roland Barthes, have plausibly argued that most popular or “classic” narratives reenact the male oedipal crisis.3 We need not list here the dreary catalogue of devices used in the male text to disable the female and thus assert masculine superiority (the grapefruit mashed in the woman’s face by one “tragic hero”). At the end of a majority of popular narratives the woman is disfigured, dead, or at the very least, domesticated. And her downfall is seen as anything but tragic. There re other ways in which male texts work to insist implicitly on their difference from the feminine. Sometimes this is done through language: for instance, through rigorous suppression of “flowery” descriptions or the tight-lipped refusal to employ any expression of emotion other than anger.

Criticism, too, finds it necessary to enhance the superiority of its objects: the male hero and the male text. The temptation to elevate what men do simply because men do it is, it would seem, practically irresistible. (Freud himself succumbed to it. As Kenneth Burke points out, Freud, in his efforts to deflate the ego’s pretensions, to show what ignoble fears and shameful desires lurk beneath the beauties of civilization, wound up glorifying these fears and desires by invoking Oedipus, one of the most grandiose figures of Western myth: The Little-Man-Fearing-For-His-“Widdler” as Tragic Hero.)4 Further, criticism, like the text itself, often raises its object at the expense of the feminine. Not only does the critical equation of pen and penis, discussed by Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar in The Madwoman in the Attic, suggest that women lack the necessary equipment to write, or at least to write well, but the feminine text itself is often used as a standard by which other products are measured and found to be not wanting. How often have we seen soap operas used in this way? Even as serious and sensitive a critic of mass culture as Raymond Williams can write, “Since their origins in commercial radio in the thirties, many serials have been dismissed as ‘soap opera.’ Yet …” And the implication, borne out in the rest of the paragraph, is that a necessary if not a sufficient criterion for the worth of serials is their difference from the (utterly dismissable) soap operas.5

Given this pervasive scorn for all things feminine, it is hardly surprising that since the beginnings of the novel the heroine and the writer of feminine texts have been on the defensive, operating on the constant assumption that men are out to destroy them. In the earliest plots the heroine was forced to protect her social reputation against the seducer who would rob her of this most prized possession. Similarly, the woman writer worked to protect her literary reputation against the dastardly critics. To aid her heroine in the protection of her virtue the writer, like male authors but for different reasons, had to disable her: for example, to render her entirely ignorant of the most basic facts of life so that the man, finally impressed by her purity, would quit trying to destroy her and would, instead, reward and elevate her—that is, marry her. What is worse, in her anxiety to ward off critical scorn, the woman writer had to disable herself, to proclaim her weakness and ignorance loudly and clearly, hoping to be “mercifully spared.” One fairly typical preface reads:

When I attempt to interest an impartial Public in favour of the following Work, it is not from a vain hope, that it is deserving of the approbation of the judicious.—No, my hopes are better founded; a candid, a liberal, a generous Public will make the necessary allowances for the first attempt of a young female Adventurer in Letters.6

Thus, if self-aggrandizement has been the male mode, self-abasement has too frequently been the female mode.

As if this were not enough, the criticism written by women has long been in the habit of denigrating what George Eliot called “Silly Novels by Lady Novelists.”7 Of course, plenty of male critics spurn silly novels written by either sex, but their criticism never seems to be so personally motivated. Eliot, for example, wrote her essay out of concern that men would find in these novels proof of the universal inability of women to write anything but silly works. Thus women’s criticism was also often written out of self-defensiveness and the fear of men’s power to destroy.

Heroines of contemporary popular narratives for women continue to act defensively, and if their writers are no longer apologizing for their activity, women critics are more than ever uncomfortable with these narratives. Such discomfort is, to a certain extent, justified, but what is most striking is that it too seems to manifest a defensiveness which has not been felt through. Whereas the old (and some of the new) heroines have to protect themselves against the seductions of the hero, feminist critics seem to be strenuously disassociating themselves from the seductiveness of the feminine texts. And whereas the heroine of romance, as we shall see, turns against her own better self, the part of her which feels anger at men, the critic turns against her own “worse” self, the part of her which has not yet been “liberated” from shameful fantasies.

Thus women’s criticism of popular feminine narratives has generally adopted one of three attitudes: dismissiveness; hostility—tending unfortunately to be aimed at the consumers of the narratives; or, most frequently, a flippant kind of mockery.8 This is the tone used by Eliot, with whom one does not usually associate it. It is, significantly, indistinguishable from the tone men often use when they mention feminine popular art. Again, the ridicule is certainly to some extent justified (though no more justified than it would be if aimed at much male popular art), but it often seems to betray a kind of self-mockery, a fear that someone will think badly of the writer for even touching on the subject, however gingerly. In assuming this attitude, we demonstrate not so much our freedom from romantic fantasy as our acceptance of the critical double standard and of the masculine contempt for sentimental (feminine) “drivel.” Perhaps we have internalized the ubiquitous male spy, who watches as we read romances or view soap operas, as he watched Virginia Woolf from behind the curtain (or so she suspected) when she delivered her subversive lectures at “Oxbridge,” or as he intently observes the romantic heroine just when she thinks she is alone and free at last to be herself.

The resent work was conceived and undertaken out of concern that these narratives were not receiving the right kind of attention. I try to avoid expressing either hostility or ridicule, to get beneath the embarrassment, which I am convinced provokes both the anger and the mockery, and to explore the reasons for the deep-rooted and centuries-old appeal of the narratives. Their enormous and continuing popularity, I assume, suggests that they speak to very real problems and tensions in women’s lives. The narrative strategies which have evolved for smoothing over these tensions can tell us much about how women have managed not only to live in oppressive circumstances but to invest their situations with some degree of dignity.

Although there have been few serious or detailed studies of contemporary mass art for women, popular feminine narratives of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries have received much more attention. Some scholars have pointed to the enormous influence of these older narratives on contemporary life and letters. Ann Douglas, for example, holds the nineteenth-century novels by and for women responsible for many of the evils of mass culture. Discussing Little Eva of Uncle Tom’s Cabin as a typical “narcissistic” heroine, Douglas says, “Stowe’s infantile heroine anticipates that exaltation of the average which is the trademark of mass culture.” And further, “The pleasure Little Eva gave me provided historical and practical preparation for the equally indispensable and disquieting comforts of mass culture.”9 Although I think this is going a bit far, the more modest claim that early popular novels for women anticipate the narratives which women find compelling in the twentieth century is certainly demonstrable. Therefore, the debates which even now surround the early narratives (What was their worth? What function did they serve?) are of relevance to any consideration of the later ones.

II

To introduce an admittedly overschematized lineage for the three forms under consideration, Harlequins can be traced back through the work of Charlotte Brontë and Jane Austen to the sentimental novel and ultimately, as I shall have more than one occasion to note, to the novels of Samuel Richardson, whose Pamela is considered by many scholars to be the first British novel (it was also the first English novel printed in America); Gothic romances for women, also traceable through Charlotte Brontë, date back to the eighteenth century and the work of Ann Radcliffe; and soap operas are descendants of the domestic novels and the sensation novels of the nineteenth century. In turn, the “antecedents” of the domestic novels, according to Nina Baym, “lay … in the novel of manners, with its ‘mixed’ heroine as developed by Fanny Burney, and even more in the fiction of the English women moralists—Mrs. Opie, Mrs. Barbauld, and especially Maria Edgeworth, with her combination of educational intention, moral fabulating, and description of manners and customs.”10

My classification is, as I say, overschematized, for the genres do overlap. Thus the plot of the sentimental novel, which often depicts a young, innocent woman defending her virginity against the attacks of a rake, who might or might not reform, would frequently find its way into the domestic novel, which tended to center around women’s activities in the home. The following is a description of the routine of the heroine of Susan Warner’s enormously popular Queechy:

By the most conservative estimate, Fleda performed the parts of three hired men, cook, dairy manager, nurse, and teacher. Up before dawn to do the chores and to care for the livestock, she found time before breakfast to study the latest agricultural methods by which she turned a rundown farm into the show place of the county. The produce from her truck garden commanded the highest prices at market and her new method of haying resulted in the banner crop of the year. In addition to the cares involved in these enterprises, she blacked the boots of her numerous guests, revived the drooping health of an ailing family, and improved her mind by reading and study. Her leisure moments, which were necessarily limited, were spent in dodging the persistent efforts of the villainous Thon, who devoted his full time to plotting her seduction!11

Here is a very potent feminine fantasy, common to most nineteenth-century novels and to their twentieth-century counterparts. The man, whether he is plotting the woman’s seduction or, as in soap operas, endlessly discussing his marital woes with his coworkers at the hospital, spends all his time thinking about the woman. Even when he appears most indifferent to her, as he frequently does in Harlequin Romances, we can be sure he will eventually tell her how much the thought of her has obsessed him. Thus, women writers have always had their own way of “evening things up” between men and women, even when they seemed most fervently to embrace their subordinate status.

The sentimental novel flourished in America at the end of the eighteenth and in the early nineteenth century. It was, however, an English import rather than an indigenous American product. Like the Harlequins of the present day, the novels repeatedly insisted on the importance of the heroine’s virginity. In the classic formula, the heroine, who is often of lower social status than the hero, holds out against his attacks on her “virtue” until he sees no other recourse than to marry her. Of course, by this time he wants to marry her, having become smitten with her sheer goodness. The early women novelists became preoccupied, not to say obsessed, with the morality of this plot. Whether or not a rake would really reform was a burning question: some novelists said no, some said yes, and many said no and yes—i.e., put themselves on record as being opposed to the idea that a rake would ever improve his morals and then proceeded to make an exception of their hero.

In these debates, however, the sexual double standard was seldom seriously challenged; very few women went so far as one female character, who, in any case, is not the heroine of the novel: “I could never see the propriety of the assertion [that reformed rakes make the best husbands]. Might it not be said with equal justice, that if a certain description of females were reformed, they would make the best wives?”12 Rather, the inequality between the sexes was dealt with in other ways. According to J. M. S. Tompkins, for instance, the effect of the “cult of sensibility,” the belief that people are innately good and that this goodness is demonstrated in elaborate displays of feeling, “was to induce some measure of approximation in the ethical ideals and emotional sensitiveness of the two sexes.” Approval was therefore given to the hero who exhibited an “almost feminine sensibility.”13 In Harlequins, the battle continues to be fought out not in the sexual arena, but in the emotional and—stretching the term—the ethical one. If ...

Table of contents

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction to the Second Edition

- 1 MASS-PRODUCED FANTASIES FOR WOMEN

- 2 THE DISAPPEARING ACT

- 3 THE FEMALE UNCANNY

- 4 THE SEARCH FOR TOMORROW* IN TODAY’S SOAP OPERAS

- Afterword

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index