![]() Part I

Part I![]()

1 Religious extremism in Britain and British Muslims

Threatened citizenship and the role of religion

Maria Sobolewska

Introduction1

After 11 September 2001 (9/11) a largely ignorant British public was thrown into the complex world of Islamic extremism and its animosity towards Western values and societies. Through many subsequent attacks on Western societies, culminating in the bombing of London’s transport system on 7 July 2005 (7/7), the Islamic threat was, in the eyes of the British public and the government, growing and coming closer to home. In the process, many myths and confusions were raised to the status of accepted wisdom. One of the most powerful of those is the question of the role of Islam as a religion and a value system in the actual and potential support of Muslims for political extremism. The growing fear of Islamic religious radicalization feeds fears of Muslim religiosity per se, and its perception as a first stepping stone towards hostile anti-Western attitudes. In Britain, but also in most of the Western world today, the public debate is hindered by such confusion about the link between the religious and the political and the assumed connection between religiosity with potential for political extremism.

It has been argued before that Islamic extremism, especially in its violent form, has been historically a political rather than a religious phenomenon (Giuriato and Molinario 2002; Pargeter 2008). Today, in the British context, this political character of extremism is being largely ignored both in the media and in most of the academic literature, and instead the role of religiosity and religious extremism is unduly emphasized. Some authors claim that the refusal of both Muslim communities and the British government to acknowledge the role of Islam as a fundamentally anti-Western religion in the 7/7 terrorist attacks on London contributes to the threat of similar attacks taking place in the future (Bawer 2006; Phillips 2006). Such focus on the cultural and religious roots of extremism, rather than their political aspects, can also be found in studies generally very sympathetic to Muslims in Britain (McRoy 2006). All these accounts share the more or less explicit assumption that something fundamentally Islamic is responsible for the threat of terrorism coming out of this community. The concept of ummah, Muslim community, is particularly held responsible for tacit support for terrorism among European Muslim communities (Bawer 2006; McRoy 2006; Phillips 2006). This tendency to place the blame for terrorism on Islam as a religion, rather than as a political movement in a particular historical and geographical context, promotes a general fear of Muslims, and in particular religious Muslims, as potential or tacit supporters of extremism and terrorism.2

Another piece of accepted wisdom surrounding British Muslims’ potential support for terrorism is the link between the radicalization of young male British Muslims and the supposed alienation and self-segregation of Muslim communities from mainstream society. On both sides of the debate, those blaming the government for being too lenient towards undemocratic and intolerant Muslim communities (Bower 2006) and those aiming to coax the government into addressing the problems of Muslims’ socio-economic disadvantage (Saggar 2008),3 the failure of Muslims to integrate into Western society is thought to be a key factor behind the attractiveness of Islamic extremism.

The causal relationship between various social and political grievances and ideologically right-wing convictions is translated into a parallel link between exclusion and disadvantaged Muslims, and their support for fundamental religious values and increasing religiosity. This, in turn, is assumed to make them more vulnerable to the attractions of political extremism, both explicitly and in terms of ‘soft’ or ‘tacit’ support, which is usually assumed to be more widespread than the fringe who openly support terrorist acts (Shore 2006; Saggar 2008). Thus both religious Muslims and those who experience poverty, discrimination, social isolation and political alienation are branded as potential sources of recruits for organizations proposing and exercising violence in the name of Islam. This picture implies that most Muslims who thus far have not been radicalized or engaged in Islamic politics they either secretly condone them thus providing it with ‘moral oxygen’ (Saggar 2008), or may do so in the future. Muslim religious identity emerges in the eyes of public opinion as an alternative, rather than coexisting, identity for British Muslims, fuelled by the argument that Muslims turn to religion following their failure to integrate with mainstream British society, or their dissatisfaction with their place within this society.

These two logical steps: (1) from religious affinity to Islamic political extremism and (2) from alienation from the mainstream society to increased affinity to religion have, to date, too little empirical support to justify their status as conventional wisdom in both the media and a large proportion of academic literature. This chapter will aim to redress this problem. First, it will take stock of the polling evidence often used in support of the notion that Islamic identity is an un-British and anti-democratic alternative to the loyal and upstanding approach expected of British citizens. Second, it will challenge the picture of British Muslims as an alienated community on the verge of seeking alternatives to their British identity. It will concentrate on religious and young Muslim Britons to show that these two groups often thought to be most vulnerable to the attractions of extremism may not be as susceptible as is usually assumed. I will argue that religion has little to do with British Muslims’ sense of alienation and their ambivalence towards the British state or society.

Sources of evidence: data and its quality

I will look at a mixture of evidence. First, I will look at a selection4 of public opinion polls conducted among British Muslims in the aftermath of 7/7 bombings. These can potentially tell us two things: first, they can give us an idea about public and media concerns at the time, i.e. the reasons why these questions were asked in the first place; second, they can give us an answer to what respondents, who were asked these questions, thought. This second issue is a more tricky matter as it is affected by the frequently poor quality of opinion polls, which prevent us from drawing any strong conclusions from this source alone. Studies using these surveys at face value, as well as more popular publications, usually draw the well known picture of alienated Muslim community (Phillips 2006; Field 2007) – a picture belied by analysis of large-scale probability surveys (Maxwell 2005).

First of all, the sampling frames of these polls are usually very poor. They are small samples not drawn probabilistically, and hence over-representing specific types of people: those easier to find and more likely to respond to the pollster. On the one hand, those with the strongest views are more likely to want to express their opinion and hence answer a survey; on the other hand, those who subscribe to extreme views may give socially desirable, rather than truthful answers to the survey questions. Most often the samples are quota samples or Internet-based samples that are largely unrepresentative. Additionally, polling houses often weight the responses of their respondents to achieve a sample that represents the demographics of a certain group (and rarely report it) and so, if they do not have enough young people in the sample, they will simply multiply their responses to achieve ‘more’ young people. This makes the proportions quoted by these polls doubtful at best. The largest problem is the lack of transparency about these problems and how they affect the data. The large-scale national surveys often struggle with these problems as well, but they are much more transparent about their methodology with regards probability sampling, non-response, probabilities of being selected are made fully public, rather than the oblique descriptions of quota samples used in polling of Muslims.

Another problem is the lack of comparability with the white population in general, or with similar situations faced by other groups. For example, many polls asked Muslims about their attitudes towards freedom of speech following the affair with Danish cartoons, which depicted the Prophet in a manner offensive to Islamic doctrine, and compared them to the general population, a spurious comparison group. A more appropriate comparison would be with the attitudes of devout Christians after the scandals surrounding such films as The Life of Brian or The Last Temptation of Christ, or more recently the show Jerry Springer the Opera in London’s West End. Last, but by no means least, these polls often suffer from many problems of question wording, as discussed in greater detail below. Responses to questions on sensitive issues such as support for terrorism are subject to serious reliability concerns, and as a result more sophisticated academic surveys have not generally asked such problematic questions. Sadly, this means there is no reliable data source available for comparison in assessing potential quality issues with the media polls.

Keeping these limitations in mind, this chapter will mainly rely on public opinion data as a gauge of changing public concerns about Muslims and Islam rather than as an accurate guide to mainstream British Muslim public opinion. For this purpose the chapter will use a nationally representative survey with high quality sampling and good measurement: the 2007 Citizenship Survey (CS).5 This survey contains an over sample of Muslims and other minorities, and employs more established and consistent measures of attitudes of interest than the temporal and often vague measures in public opinion polls. This dataset contains 14,095 respondents, among whom 1,784 identify themselves as Muslims. The sample reflects the ethnic diversity of Muslims in Britain: 44 per cent are Pakistani, 16 per cent are from Bangladesh, 13 per cent have Indian background, 10 per cent are of African origin, and a small minority of 4 per cent are either of mixed origin or identify themselves as white (this most probably includes some Arabic Muslims). The CS sample includes people aged 16 and over, which ensures a good proportion of young Muslims as ethnic minorities tend to have a lower average age. Overall, 26 per cent of Muslims in the sample are born in the UK.

Where do their loyalties lie? Support for terrorism and Islamic religious identity as an alternative to British identity

British public’s fear of Islamic extremism and Muslims’ support for terrorism

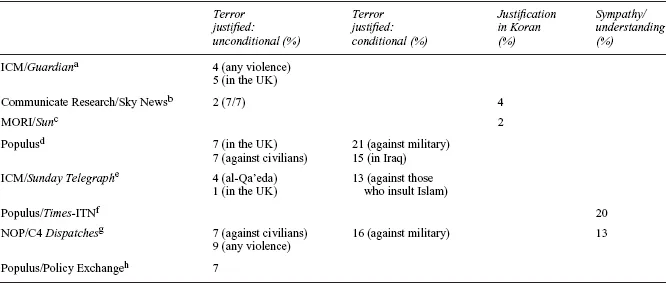

Why is the loyalty of British Muslims questioned and their religious identity regarded as suspect after a mere handful of British Muslims were engaged in the horrific attack of 7/7? This is a strong worded question, but it is clear when one looks at recent polls that after the 7/7 attacks there existed in Britain widespread concern over support for terrorism and violence among Muslims. The aftermath of 7/7 saw a large number of public opinion polls conducted among British Muslims. In our sample of polls six were interested in Muslims’ Islamic and British identity between July 2005 and December 2006, eight asked about Muslims’ attitudes towards terrorist attacks in general and in a variety of specific contexts. As we can gather little direct information about the small number of Muslims actively supporting terrorism from these polls, due to methodological constraints of measuring extreme attitudes,6 the focus of these polls has been upon concern over ‘tacit’ support for terrorism and on estimating the proportion of Muslims who proffer it and thus provide ‘moral oxygen’ for extremism (Saggar 2008). A look at Table 1.1, where recent polling questions are summarized, shows clearly the concern with Muslims’ tacit support for terrorism.

Generally there are two ways in which British Muslims were asked about their support for terrorism; one in absolute, unqualified terms, and the other in ways that allowed for various circumstances and considerations, clearly designed to get at the ‘tacit’, weak and subtle support that supposedly provides ‘moral oxygen’ to terrorists. The answers to these two types of questions are strikingly different. On the one hand, very few Muslims (between 2 and 5 per cent) support political violence and terrorism in general, the specific attacks of 7/7 or agree that terrorism is justified in the Koran (ICM/Guardian July 2005; Communicate Research/Sky News July 2005; MORI/Sun July 2005). On the other, when asked whether they find any personal sympathy with the motives behind the 7/7 bombings (Populus/Times-ITN June 2006), asked if terrorist attacks against military targets (Populus December, 2005; NOP/C4 Dispatches April 2006) or against those who offend Islam (Populus/Times-ITN June 2006) can be justified; or simply asked whether they ‘understand’ the terrorists (NOP/C4 Dispatches April 2006), between 13 and 21 per cent of Muslims respond positively. Similar contrasts are seen even within the same survey: the Populus/Times-ITN poll in June 2006 shows simultaneously that 20 per cent of Muslim respondents have personal sympathy with terrorists, 1 per cent agreed that the 7/7 attacks were ‘right’ and 13 per cent thought violence against those who offend Islam was ‘right’. It seems unsurprising that fewer people condone violence and terrorism outright and more are ready to concede that some situations may justify them. It is equally to be expected that even more people concede that they ‘understand’ or ‘sympathize’ with terrorists’ way of thinking. It would be hardly striking if non-Muslim people showed similar patterns of response. The question however is whether these Muslims who ‘understand’ and ‘sympathize’, or who justify violence under some circumstances represent the ‘tacit’ or potential supporters of terror that the polls are trying to get at.

Table 1.1 Support for terrorism? Public opinion polls, 2005–2006

Notes

a Interviewed 500 Muslim respondents 15–20 July 2005.

b Interviewed 462 Muslim respondents 20–21 July 2005.

c Interviewed 282 Muslim respondents 21–22 July 2005.

d Interviewed 500 Muslim respondents 9–19 December 2005.

e Interviewed 500 Muslim respondents 14–16 February 2006.

f Interviewed 1,131 Muslim respondents by telephone (750) and online (381) 1–16 June 2006. The national sample comprised 1,005 respondents interviewed 9–11 June 2006.

g Interviewed 1,000 Muslims 14 March–9 April 2006.

h Interviewed 1,003 Muslim respondents 4–13 December 2006.

An examination of how questions are asked by these polls gives the impression that they are ‘fishing’ for the desired answer. The polls conducted soon after Muslim terrorism became a public concern in the wake of the 7/7 bombings simply asked whether terrorist attacks were justified and violence was acceptable. These were simple questions and were normally answered simply and consistently ‘no’. However, results like those make no headlines and sell no newspapers, and as we move away from the time of the attacks the questioning grew more complex, adding various qualifications and circumstances under which attacks may take place and asking about various other attitudes towards them such as sympathy and understanding. These later polls then showed much higher levels of apparent Muslim support for terrorism, clearly reflecting the public preoccupation with the potential for tacit and weak forms of support.

Sadly, the questions being asked to gauge this clandestine or potential support are not very well designed. One problem is the employment of certain words, such as ‘right’ or ‘wrong’, ‘sympathy’ and ‘understanding’, which respondents and pollsters may interpret differently. To give one example, it is not clear what we may conclude from the fact that 20 per cent of Muslims said they have personal sympathy with terrorists’ motives (Populus/Times-ITN June 2006). Is this a sign of ‘soft’ support for terrorism? Is this the group that provide moral support? Or does this simply mean they can understand the terrorists’ thinking, while disagreeing with it themselves? Many left-wing white Britons, one could imagine, would express personal sympathy with the motives of Palestinian terror groups, but this does not ...