![]()

1

CULTURAL AND RELIGIOUS CONTEXTS

The “Middle East” is an enormous and diverse region of the world linked together by historical, cultural, linguistic, and religious connections, including legacies of the empires of Greece, Rome, the Arabs, the Ottoman Turks, and European and American imperialism. The region can be defined in a number of ways. For the purpose of this book I will use the definition that includes North Africa (Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Sudan, Eretria, Somalia), the traditional “Middle East” (Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Oman, Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, Turkey, Jordan, Iraq, Iran, Kuwait, Arab Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain) and, especially because of the contemporary conflict there, Afghanistan. Even though this definition is certainly broad enough for this project, it could be even broader as many other countries might also be considered part of the “Middle East” (including Western Sahara, Mauritania, Ethiopia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan, even Pakistan). The region we will consider the “Middle East” has a current population of about 540 million people (the United States has 307 million) and an area of nearly 8 million square miles (the United States comprises 3.8 million square miles). The Arabian Peninsula by itself is about the same size as the United States east of the Mississippi plus Texas and California. The enormous region of the Middle East represents a great diversity of land forms at the intersection of three continents, including mountain ranges, seas, oceans, rivers fed by winter snowfall, fertile soils as well as deserts, Mediterranean and temperate climates.

We should recognize also that the term “Middle East” is not one that originates in the region or reflects how people who live there name or define themselves. Instead it is a Eurocentric expression that likely first emerged in the 1850s in the British offices administering their India colonies.

The very appellation [“Middle East”] is a creation of colonialism, for this region is “Middle” simply because the point of reference, in more than one way, is Europe. People who live in these countries understand themselves to be “Middle Easterners” only in relation to the West, and use the term primarily within the context of discussion of geopolitical considerations and configurations of world powers. Their own self-designated parameters of identity would not include this category. No one would say: As a Middle Easterner, I …, while people do say, “as an Arab,” “as an Egyptian,” “as a Muslim,” in addition to “as a woman,” “a physician,” “a Marxist,” etc. If people of the region want to use a more encompassing designation that transcends national, linguistic, or religious classifications, they tend to use the term, “peoples of the third world.”

(Al-Nowaihi, 283)

The term “Middle East” is surprisingly recent. It gained recognition when it was used by an American naval strategist in an article published in 1902 to designate the area between Arabia and India (Koppes, 95). Parts of this region had also been known as the “Near East,” as opposed to the “Far East” of China, Korea, and Japan. It wasn’t until the 1950s that the term began to be used by U.S. government officials.

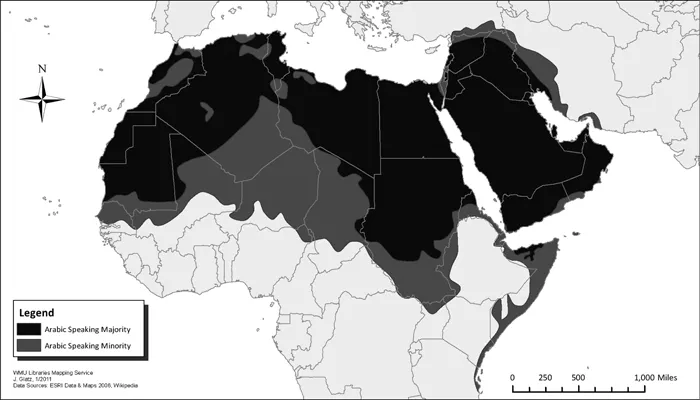

Portions of what we now call the “Middle East” were politically connected by Greek, Roman, Persian, and Byzantine Empires, but the most important empire for shaping modern linguistic and cultural identity of the region was the Arab empire that arose in the first generations after Muhammad’s death (632 CE) and lasted nearly 800 years. By 750 CE the Arab empire included Arabia, Syria, Egypt, North Africa, Spain, Persia, Armenia, Afghanistan, and portions of Pakistan and India – a significantly larger area than we now call the “Middle East.” Variations of the Arabic language are spoken across North Africa and the Arabian Peninsula as the map indicates.

BOX 1.1 APPROXIMATE NUMBER OF SPEAKERS OF MIDDLE EASTERN LANGUAGES

• Arabic 280 million native speakers, 250 million non-native

• Persian 60–70 million

• Turkish 70 million

• Kurdish 26 million

• Hebrew 7 million

• Armenian 7 million

• Berber 10 million

FIGURE 1.1 Approximate Number of Speakers of Middle Eastern Languages

At the time of Muhammad, the Arabs were frequently described as sharing virtues necessary for nomadic life in the desert, “bravery in battle, patience in misfortune, persistence in revenge” (Ochsenwald, 19). There was an emphasis on protection of the weak, defiance of the strong, hospitality to the visitor, and generosity to the poor. Loyalty to the tribe and fidelity to promises were highly valued. Codes of desert revenge existed to enforce justice under a system without formal government and penal codes. There were also ideals that might be seen as loosely democratic, with clans independent from each other, decisions made by assemblies of chiefs, and unity created by negotiation.

Islam spread quickly not simply from conquest, but because the Muslims were found to be more liberal than previous empires and local authorities. Muslim rule generally meant religious freedom and lower taxes. Non-Muslims could not bear arms, but were allowed to maintain their own laws and culture. Muslims were actively involved in commerce, facilitated by reading, writing and a common language. Indeed, the European “dark ages” was a time of Arab cultural flowering. Muslim culture assimilated Greek, Roman, Persian, and Hindu learning and Arabic provided a lingua franca for theology, philosophy, science, and the humanities, including poetry. While there was certainly oppression of women in the Arab empire (and in Europe at the same time, of course) during Muhammad’s day some women had significant freedom and public roles. Interestingly, the veiling and seclusion of women was not originally a Muslim practice – it was adopted from Byzantium.

As the Arabic language became increasingly used throughout the enormous region of the Middle East, the definition of who was “Arab” also evolved. An “Arabic” person became someone who identified as Arab on ethnic, linguistic, or cultural grounds. “Arab” was never a religious category – there were Christian and Jewish Arabs long before Islam, and significant numbers of Arabs today are Christian and Jewish. “Arab” was not a racial category: there are white, black, and brown Arabs.

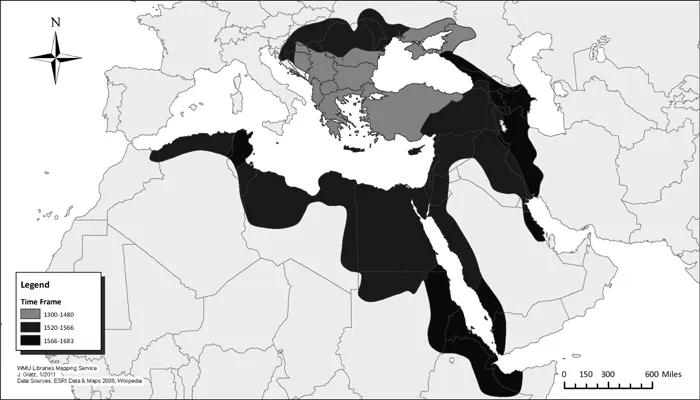

In the fifteenth century the Arab Empire was replaced by the Ottoman Turks. The Ottomans had accepted Islam, and the sultanate and caliphate (political and religious governance) were eventually centered in Constantinople, modern day Istanbul. The Ottoman Empire was one of the largest, richest, and longest lasting in world history. It included an enormous territory in areas we now consider Middle East, North Africa, and Europe. The Ottoman Empire was a multi-ethnic state where Turkish was the language of governance, Arabic the language of religion, and many citizens also spoke one or more local or regional languages. The Ottoman Empire was multi-religious; for most of its history the majority of its citizens were Christian (in Southern and Eastern Europe as well as throughout the Middle East) and there were many flourishing Jewish communities accepted after they fled from persecution or were expelled from countries in Europe, especially Spain and Portugal. (At one time or another Jews were also expelled from England, France, Germany, Poland, Russia, and many other countries.) The diverse and sometimes conflictive ethnicities and religions (including Sunni vs. Shiite Islam) were more or less held together under the aegis of empire. There was extensive trade and the Sultan accumulated enormous wealth. Like the rest of the world at that time, most people were employed in agriculture. Again like the rest of the world, outside the capital cities and the military, formal education beyond religious teaching was poorly developed. Given the extent of the empire, rural areas were sometimes loosely governed, local elites had significant authority, and at times banditry was common. Throughout the Ottoman period various efforts were initiated to reform land ownership, standardize military training and, especially near the end of the empire, to establish technical education on the Western model, including the education of women. The extensive and lengthy Ottoman Empire further developed political, social, and cultural connections between the Middle East and North Africa. The region of Iran remained separate, though Islamic and subject to the Caliphate in Istanbul. Corruption, intrigue, and the cost of conquests weakened the Ottoman Empire and the rising power of Europe increasingly threatened its rule.

FIGURE 1.2 Ottoman Empire

After World War I and the defeat of the Ottoman Empire, the victorious European powers dominated the region. Since the end of World War II increasing American intervention in the region has profoundly shaped today’s Middle East. I narrate this crucial history in Chapter 5.

Religions of the Middle East

The Middle East is the home to many religions, including the three great monotheistic “religions of the book,” Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Teaching contemporary literature from the Middle East the theme of religion will come up. Religion permeates life. Consider, for instance, the importance of religion to the British literature we teach in schools, from Beowulf and The Canterbury Tales to John Donne and John Milton, to Graham Greene and T.S. Eliot. Religion will also come up in the study of the Middle East because English-speaking students have many stereotypes and misconceptions, above all about Islam, but also about Judaism and about Christianity. Conflicts between Islam, Christianity, and Judaism have had much more to do with control over land and economic resources than differing religious belief (a topic I return to at several points), though the conflicts have provoked religious misunderstanding and animosity. Some measure of religious education, and some effort to address and dispel religious stereotypes is an appropriate part of teaching literature of the Middle East.

Judaism

At 4,000 years old, Judaism is the oldest monotheistic religion in the world. World Jewish population is estimated to be about thirteen million, with about five million in the U.S. and a like number in Israel. In the Jewish faith no one person or organization has authority on theological or legal matters, which have been interpreted for centuries by rabbis and scholars from the Hebrew Bible, the Torah, and from commentaries such as the Talmud and Midrash. There are many different beliefs in Judaism; the faith tends to be organized as Orthodox, Conservative, or Reformed, depending on how liberally texts are interpreted. The study of the Torah is considered a means of understanding God, and there is a long and deep scholarly tradition in Judaism. Because of its complex history, Judaism does not fit simply into categories as a religion, an ethnicity, or a culture, but draws on all of these. Indeed, the very definition of who is “Jewish” is debated. Some Jews view themselves as “secular” meaning that Judaism may be an important aspect of their lives, but they typically don’t attend synagogue, hold traditional beliefs, nor engage in religious practice. The Ashkenazi (“Western”) Jews, who comprise 80 percent of the world’s Jewish population, trace their ancestry to medieval Jewish communities along the Rhine River in Germany that spread through Eastern Europe and spoke Yiddish, a Germanic language much influenced by Hebrew. Sephardic Jews, up to 20 percent of Jews, are descended from those who were expelled from Spain and Portugal in 1492 and 1497, though the term is also used more broadly to include Jews of North Africa and Asia (these Jews are also referred to as Mizrahim). The Jews who were expelled from Spain settled in Morocco, Turkey, throughout the Ottoman Empire, and elsewhere.

Traditionally Jews pray three times a day, with a fourth prayer on holidays. The Shabbat or Sabbath is a day of rest from sundown on Friday to just after sundown on Saturday. Jewish holidays include Yom Kippur (a day of fasting and forgiveness of sins), Rosh Hashanah (new year), Passover (commemorating the exodus from Egypt), and Hanukkah (re-dedication of the temple). Of course, there is so much more to learn about Judaism, and many helpful books and resources. I have found many Jewish people, including rabbis, to welcome the opportunity to speak with students about the Jewish faith.

Teaching about the Middle East, especially Israel and the Israel–Palestine conflict, may bring up for students, parents, or community members the issue or topic of anti-Semitism. Given the long history of anti-Semitism in our culture and in literature in English, including in our most canonized authors, it is important for teachers to address it. My 2001 book Literature and Lives opens with the story of my experience teaching Elie Wiesel’s Night, and bringing an Auschwitz survivor, Diana Golden, to my high school classroom. In that book I set forward materials and approaches for teachers to address the Holocaust in an historically grounded way, and I offer ideas for helping students examine anti-Semitism in literature including in works by Chaucer, Shakespeare, Dickens, George Elliot, Ezra Pound, and T.S. Eliot. Over my thirty years of teaching I have continued to bring Holocaust literature and survivors to speak to my students, now future teachers themselves, and to take future teachers to synagogues and invite rabbis to my class to help students learn about the Jewish faith and the history of the Jewish people. I also continue to publish on the topic of teaching about anti-Semitism (“A Multimodal Approach to Addressing Anti-Semitism,” 2006). In Literature and Lives, I describe how “teaching a Holocaust unit touched something in me that began to enlarge my vision of English teaching” (Carey-Webb, 3). In important ways, the values, commitments, and approaches I have learned as a teacher addressing anti-Semitism have brought me to this current project, addressing literature of today’s Middle East.

All in all, our students need to learn to recognize and resist the long history of racism, discrimination, pogroms, expulsions, and genocide against Jewish people. And, they need to know that anti-Semitism is alive today in global conspiracy theories, right-wing militias, and outright violence and racism against Jews. Indeed, and perhaps for good reason, many Jewish people around the world think of Israel as the sanctuary of last resort, should anti-Semitism again represent a danger.

Because Israel plays this role, and because Jewish people have suffered so much, especially in the Holocaust, it is difficult for many people, including many Jewish people, to criticize Israel. Yet, teachers who read, teach, and address the contemporary Middle East are going to come across literary, cultural, historical, and political works that openly and powerfully criticize Israel, particularly its treatment of Palestinians and its Arab neighbors. This book includes such works, and it is also important that we and our students read and understand them. Teaching the Literature of Today’s Middle East also presents literature and film from Israel appropriate for teaching to young adults. Arabs are ethnically Semitic people, and, as I have discussed and we will see further, there are similarities in racist depictions of Arabs and of Jews.

Let me be clear on one point. It is possible to teach about the Middle East and/or criticize the politics of the state of Israel, without being anti-Semitic. Teachers who address the Middle East should know that some of the strongest criticism of Israel, and specifically Israel’s treatment of Palestinians, is made by Israelis themselves, and by prominent American Jews from Noam Chomsky to Jon Stewart. While there are different versions of Zionism, one of the fundamental ideas of political Zionism is that Jewish people have a special right to the land of Israel, a right that supersedes the claims of the Palestinians who formed the vast majority population there preceding World War II and who, in the present day, still constitute about half the population of Israel and the Palestinian territories controlled by Israel. Yet, there are orthodox Jews who believe that Zionism is “totally contrary to traditional Jewish law and beliefs and the teachings of the Holy Torah” (“What is Zionism?”). Alan Hart’s readable ...