Chapter 1

Metabolism 1960

In May 1960, Louis I. Kahn made his first and only journey to Japan to attend the World Design Conference in Tokyo. During his time in Japan, Kahn delivered the famous talk on “Form and Design” at one of the conference seminars.1 He then presented a lecture at Waseda University entitled “City Planning and the Future of Architecture” that elaborated his concepts of urban design. Through activities in and outside the conference, he acquainted himself with Japanese architects and designers. Kahn’s brief sojourn, together with the ideas of architecture and urbanism he conveyed to his Japanese audience, earned him the reputation as one of the most influential Western architects in postwar Japan.2 One of the remarkable moments of Kahn’s visit was his encounter with a group of young Japanese architects who called themselves the “Metabolists.” The group, which formally announced itself at the World Design Conference, would soon lead Japanese architecture in a new direction.

Until 1969, overseas travel remained the privilege of limited few in Japan due to the governmental regulation restricting Japanese travel abroad after the Second World War. Visits by foreign architects to Japan were thus viewed as important events in the country where architects and designers were eager to learn about the latest developments of modern architecture from their Western guests. Prior to the World Design Conference, Walter Gropius traveled to the country in 1953 to help solve the postwar housing crisis; Le Corbusier visited Tokyo in 1955 to prepare his design for the National Museum of Western Arts; and Konrad Wachsmann offered a series of seminars at Tokyo Institute of Technology in 1956. The World Design Conference represented an even more promising opportunity for Japanese architects and designers to interact with their European and American peers. Held in Tokyo from May 11 to 16 in 1960, the conference was “the most ambitious event of its kind ever staged in Japan.”3 It assumed an important place in Japan’s postwar history as the country recovered from the war and was eager to return to the international community. Since the Japanese economy had become increasingly export-oriented, the national government placed great importance on design in order to improve the competitiveness of Japanese products. Approximately 250 architects and designers participated in the meeting, representing 27 countries. Among the participants were a cluster of stellar architects, including Paul Rudolph, Minoru Yamasaki, Peter Smithson, Jacob Bakema, Ralph Erskine, Jean Prouvé, B.V. Doshi, Ralph Soriano, and Kahn. In the Japanese delegation, three master architects, Kunio Maekawa, Junzo Sakakura – both prominent pupils of Le Corbusier – and Kenzo Tange, gave key speeches at the conference.4 They were joined by a number of prestigious Japanese industrialists and governmental officials. It was also at this occasion that the young generation of Japanese architects, represented by the Metabolists, came to the forefront of the dialogue with the Western masters.

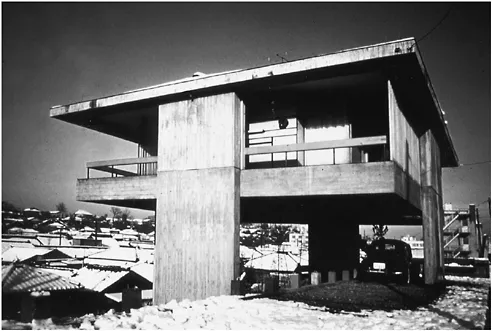

On the evening of May 13 after his lecture at Waseda University, Kahn was invited to the home of Kiyonori Kikutake, one of the Metabolist architects. The “Sky House,” as Kikutake’s house is known, was designed by the architect himself and had become an iconic building by that time. The house is essentially a square box elevated by four tall concrete panels. Unlike conventional columns supporting a building at the corners, these wide columns stand in the middle of each side, lifting the house over the hillside. Inside, under a paraboloid shell roof, is a single space divided only by storage units. The kitchen and bathroom are located on the outer edge of the space. The building provides flexibility for space arrangement with the possibility of future addition and renovation. It was planned that children’s rooms could be added underneath the platform and the utilized units could be updated periodically, both of which did actually happen. It was with this building that Kikutake first explored the idea of a building being able to respond organically to cycles of growth and decay.

In Sky House, Kahn had a long conversation with a number of Japanese architects, including the Metabolists.5 He answered questions well after midnight, with Fumihiko Maki, another Metabolist architect and then assistant professor at Washington University in St. Louis, interpreting. Kahn further discussed the distinction between “form” and “design.” Form, he explained, has no shape and no dimension; rather it represents a “sense of order” and a “harmony of systems.” Design, on the other hand, is a circumstantial act evolving from the form.6 He used a spoon as an example of this distinction. The design of a spoon can vary in terms of its material, mold, and size. That a spoon proves to be a spoon, however, is due to its form consisting of “a cup-like container and an arm,” which serves as the basis of any design.7 Kahn urged young architects to rethink the meaning of form and to base any design projects – from a spoon to an entire city – on this fundamental principle. He used his own projects, the Richards Medical Research Laboratories and the plans for Philadelphia, to explain how reorganization of spaces or movements could lead to new design solutions. Although Kahn spoke in his typically enigmatic manner, some of his ideas seemed well received by his audience. The architects, designers, and critics of Metabolism also believed in a universal language for design, whether applied to a vessel, a building, or a city. Therefore Kahn’s concepts of form and design were particularly intriguing to them. Moreover, Kahn’s megastructural approach to urbanism and the distinction of “served space” and “servant space” in architecture, as presented in his projects in Philadelphia, also inspired the Metabolists. Over the next decade, these young architects were to produce a stream of megastructural proposals. They used

Kahn’s concepts for their own interpretation of a general model of architecture and urbanism.

The founding of Metabolism

The Metabolist group emerged from the preparation for the World Design Conference. The International Design Community (IDC), which arranged the conference every four years, decided that the 1960 meeting would be hosted by Tokyo.8 Three Japanese institutional members — the Japan Institute of Architects, the Japan Association of Advertising Arts, and the Japan Industrial Design Association (JIDA) – would be responsible for its organization. Early in the planning process, however, JIDA withdrew from this conference. Since the Association of Advertising Arts was a relatively smaller group, contributing less to the IDC, the Japan Institute of Architects assumed chief responsibility for the preparation of the 1960 meeting.9 A World Design Conference Preparation Bureau was formed in 1958 under an executive committee led by Sakakura, Maekawa, and Tange. Sakakura, well connected to the political and financial circles in Tokyo, was named its chair. Thanks to his rising international reputation after the completion of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, Tange was made the director overseeing conference programs. Because Tange had accepted an invitation from Massachusetts Institute of Technology to be a visiting professor for the 1959/60 academic year, he recommended Takashi Asada, his junior colleague at the University of Tokyo, to take charge of preparing programs. Asada was appointed Secretary General of the preparation committee.10

Once in his new position, Asada formed a working team. Serving as Tange’s major assistant at his architectural laboratory in the university, Asada was active among young architects in Tokyo.11 He first called upon two of his architect friends, Noboru Kawazoe and Noriaki Kurokawa.12 Kawazoe was an architectural critic and former chief editor of Shinkenchiku (New Architecture); he had recently been forced to resign from the magazine because of his criticism of Murano Togo, another Japanese master architect known for his eclectic design style and use of expressive surface texture on large-scale buildings. Architecturally Kawazoe was sympathetic to Tange’s Corbusian modernism and wrote a few essays on his works.13 Kurokawa was Tange’s graduate student at the University of Tokyo, and he had recently traveled to the Soviet Union as the Japanese representative for an international conference of architectural students. Asada recruited Kawazoe and Kurokawa to the committee, asking them to look for additional talented architects and designers to help with the preparation of the conference.

Kawazoe and Kurokawa visited several architectural firms, design studios, and universities in Tokyo, and they engaged Masato Otaka, Kiyonori Kikutake, Kenji Ekuan, and Kiyoshi Awazu. Otaka and Kikutake were rising stars among young Japanese architects. Otaka was a chief architect at Maekawa’s office. He had recently completed the design of the Harumi Apartment Building, a mass housing project located on a reclaimed site in Tokyo Bay.14 Besides his Sky House, Kikutake was known for his series of futuristic urban projects, including “Tower-shaped City” and “Marine City,” both published in the journal Kokusai kenchiku (International Architecture) in 1959.15 Ekuan and Awazu represented the other two professional groups that constituted the International Design Community, industrial designers and graphic designers. These six young men, under the leadership of Asada, developed the programs for the World Desig...