Chapter 1

In the beginning

Educational trial and error

In the beginning

Learning is a science, not an art. Our biology determines how we learn, and how we have evolved to adapt to our environment, yet education systems do not take into account the biological basis of learning.

Consider newborn children. They have to learn to understand the whole world: the space we inhabit; the distance between objects; what people are and who they can trust; how to feed; how to move; how to understand talk, and then to talk; how to move their bodies, to crawl, to walk; to love and be loved. They do all this by sharing our world, our food and our lives. They accomplish all this in two years.

Consider the child in education. They have to learn the skills of school; they have to absorb information about thousands of things that have no immediate relevance to their lives; to read, to write (if they have not learned at home); to learn things only to forget them; to sit for hours in a day and listen to an adult; to try to learn separated from the people they love; and to take tests so they can prove themselves better than other children. They do this separate from our world, our food and our lives. Many children fail to accomplish all these things, even though billions are spent on education systems. This can take up to 20 years of their lives.

Consider the young adult. At the end of formal education, when they launch themselves back into their life, they quickly have to get a job, find a home and make a contribution to the world and themselves. They do this with us: living and working, eating our food and helping to change our world. Most of them succeed. They accomplish all this in about two years.

Education systems are, after all, relatively new. Yet a baby’s learning suggests quite a different approach from formal education: for them, learning seems an inborn disposition, a fundamental skill in our species. Education systems, however, still seem unable to take advantage of this inborn disposition. From an evolutionary and biological perspective learning is part of humanity’s biological adaptedness. We adapt to our world not only in terms of biological change (over long periods) but also in terms of our ability to learn behaviour. Adaptedness makes us better able to survive and multiply. Evolutionary biologists are quite clear about the significant advantages for a species of social adaptedness.

The transfer of knowledge and skills has changed the human condition. It is directly responsible for humans being the only living thing to escape the biological restrictions on population growth. Language, although not solely a human trait, is a fundamental feature of that ability to transfer knowledge. All these changes are outcomes of an organic, evolutionary process. In contrast, education systems are an attempt to build an abstract, formal process that transfers knowledge. Not surprisingly, education systems are not very successful – yet.

The biological basis of human behaviour is already known in very broad outline. The development of knowledge in neuroscientific, genetic and related sciences is very rapid. In due course we will understand much more, but we should not imagine that the outcome of this research will reinforce conventional wisdom about learning.

Challenges to our conventional wisdom have emerged in some important areas. It appears that human brains are continuing to evolve, possibly with radical implications. There have been recent changes in the DNA associated with brain size. These changes affect genes, where new variations, called ‘gene variants’, have occurred. At first, only a few people have these new gene variants, but two of these variants emerged roughly at the same time as our social behaviour changed. This has raised the question of a possible connection with our cultural evolution. One of these new gene variants (the ‘microcephalin variant’) appeared about 50,000 years ago, when humans began to use art and music, religious practices and sophisticated tool-making techniques. For some reason, 70 per cent of us already have this variant – a very rapid spread for a single gene variant. Thus it may have some significant benefits. The other similar genetic change (the ‘ASPM gene variant’) appeared just 5,800 years ago, when humans started to use agriculture, settled cities and began to use written language more widely. Already 30 per cent of us have this gene variant – and again this rapid spread suggests a genetic change that has significant benefits.

It seems, therefore, that changes in our genes have occurred in parallel with significant changes in our adaptedness. The researchers involved in these discoveries note that these changes have occurred in a very short period, which indicates ‘intense selection pressures’. These genetic variants have not been directly linked to intelligence (though there may be links), but the real issue is that the human brain is changing, and that there may be an interaction between genetic change and apparently learned behaviours. The implications of this are profound: have we only begun a process of evolution where interaction with human civilization changes the value (and therefore spread) of genetic variants? If so, revolutions in the knowledge we have and use may affect our evolutionary development through such mechanisms. Whatever the answer, we now know that humans have not stopped evolving, and that the barrier we have always assumed existed between our minds and our physical evolution may, in reality, not exist at all.

Does education make you fat?

The pressures on growing children today may be of a different kind than they were 200 years ago, when hunger and disease were normal, but the pressures are very real.

Things have not turned out as well as predicted 50 years ago when the economists realized that hunger could be eradicated. In The Affluent Society Galbraith argued that people in affluent societies would be free from the fear of want. Full production became the goal (though only achieved by want creation – advertising, for example) and education would create a ‘New Class’ of those that enjoyed their work and an enviable life style. How did long-term economic change really affect children? Galbraith’s conviction that an educated New Class would spring up ignored other industrial providers of pleasure in modern society, such as the fast food industry, the entertainment industry and the legal and illegal drugs industries. Education now competes with these other calls upon people’s attention. An easy demonstration of these economic realities lies in the answer to a simple question – what are the biggest dangers facing our affluent children? Depending where you live in the world, they could be crime, wars, disease or famine. But in an affluent society the reality is different. The biggest threats to children are commercial products: cigarettes, alcohol and other drugs, cars and food itself. Food is a good example. The growth of the processed food industry and advertising has a marked effect: the industry exploited our food habits, increasing our daily calorie consumption. This is because of our natural inclination to favour highcalorie foods. The consequence of this commercial activity is a strong tendency in every affluent society to become obese.

Obesity has now been described as an epidemic, and the possibility that this generation will be the first generation in which children routinely die before their parents is very real, according to the US Surgeon General. The educational response to the crisis has often been self-serving, promoting conventional wisdom and the institutional educational agenda. Educationalists have quite openly used the danger to young people to seek additional funding for programmes whose failure has been a contributing factor to the rise of obesity: traditional schooling and PE teaching.

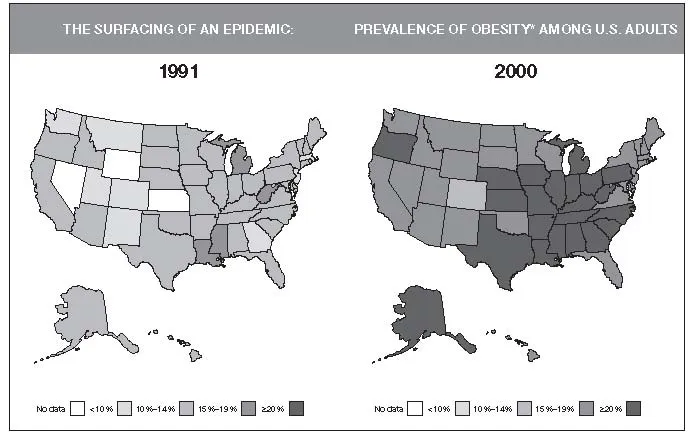

Epidemics are marked by rapid increases in disease, and the Surgeon General’s report on obesity is able to present this in a very compelling fashion, as shown in Figure 1.1. This epidemic is clearly related to the commercial and industrial approaches to food in the US and other affluent societies. The Surgeon General’s report does not attack these economic processes, though it notes that the consumption of huge quantities of high-calorie processed foods is a major contributing factor in the rise of obesity. The media focus has often been on the most obvious examples of processed foods, such as hamburgers. To be fair to the McDonald’s restaurants of the world, shopping in Wal-Mart stores in America can be just as dangerous: huge quantities of processed food items are offered at discount prices, but only when purchased in volume. It hardly encourages good eating habits.

The attempt to use this epidemic by pressure groups is instructive. For example, Lynn Swann, Chairman of the President’s Council on Physical Fitness and Sports, notes that: ‘400,000 people a year die from conditions related to physical inactivity combined with poor diet. Only smoking kills more people – 435,000 people a year. The gap is closing fast.’ But Swann then goes on to assert that: ‘a remedy already exists, [with] no costs except commitment and determination. That medical miracle is daily physical activity.’ Swann does not challenge the economic powers that be: to mention the commercial food companies, their advertising and the political power of a multi-billion dollar industry, and link these to the pernicious effect of ‘poor diet’ would be too dangerous, perhaps. The ‘medical miracle’ would not work on its own, but it would increase funding for the institutional interests Swann represents.

A factor that has never been mentioned is society’s role in children’s inactivity. For example, what has made children sit down for hours a day, focus their attention on just one thing, and isolates them from normal activities with their families and peers? School. School usually keeps children inactive at desks for many more hours than television does (though, interestingly, children who like learning at school usually like learning from television). Schools fail to challenge the commercial food providers, as well as providing poor food. Rapidly evolving new business practices (such as in the fast food industry) combined with little or no guidance from schools and parents may have produced a literally lethal combination. The epidemic has evoked a powerful response by government, at least in terms of reports and sports-based projects, but little significant headway has been made on the underlying problems.

Figure 1.1 The surfacing of an epidemic: the prevalence of obesity among US adults

Source: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS)

Note: Obesity is defined as approximately 30 pounds overweight. BFRSS uses self-report height and weight to calculate obesity; self-reported data may underestimate obesity prevalence.

Galbraith’s vision of increasing numbers of people living a healthy and fulfilled life, shaped through high educational achievement, has been undermined by economic forces from those that created affluent societies: industries. Our society is one in which fast food, cars, drugs, cigarettes, commercial products of every kind and non-stop distraction from the entertainment industry are available for everyone. Education will not be able to compete, unless it is engaging – and forthright about the limitations and dangers of a life based on consumption. In crude terms, children have economic choices that include healthy life styles, exercise and learning – or gratification through commercial products. No one should be surprised at consequences such as drug abuse or obesity.

A child’s intellectual potential

There are, however, economic forces that encourage children to succeed in education. Before turning to this, it is useful to consider the growing academic expectations of children and how realistic they are. There is no obvious limit to how intelligent children can become. In the past it has been argued that an individual’s ability to learn is limited and largely fixed by birth, race or social position. Theoretically, it now looks as if most children can achieve to a very high level. There are signs that people are actually becoming more intelligent: there apparently has been a significant increase in the IQ scores of children worldwide in the last generation.

If one examines the history of exceptionally able people, it is possible to see two types of explanation of why they are so able. Again, a historically popular view was that genius or exceptional ability was a question of an inborn gift. In contrast with this view, it is becoming clear that the answer may lie in the amount of time a child spends in a certain activity. Mozart is an example of a genius created through a rigid regimen focused on a single skill. In a recent biography Mozart’s passionate need for affection and seeming obsession with music are linked directly to his father’s focus on his commercial value as a prodigy. His father’s fixation meant that Mozart had to devote most of his waking hours to music. A similar rigid regime, but in a school, forced Christopher Marlowe, the Elizabethan playwright, to focus on literature to the exclusion of almost everything else. Of course, it is not as simple as this: neither Bach nor Shakespeare was a product of such restrictive upbringing. Application may make a huge difference, but it is probably not the only factor.

One conclusion is that it is possible to raise children in such a way that they become exceptionally able in at least one area. We have yet to understand this process, or to apply it in learning. The dreams of parents for their children to achieve great things are, therefore, justified; their tragedy is that, at the moment, they are unlikely to be realized.

A child’s economic potential

There are clear economic incentives that encourage children to succeed in education. Young people earn more money if they are educated to a high standard, and this is a driving force behind parents’ desire to see their children do well. There is, of course, a tendency to think of this process as a competition against other people’s children rather than an attempt to universally raise levels of achievement, as education is another social indicator of a successful life.

Most people believe in the value of education in principle, even if it is only the economic value of education. Although they may think education has improved, they still criticize what happens in schools and universities. This suggests that they believe education is a good thing in economic terms, but are disappointed with the effectiveness of the education they and their children have received. This collective perception is a fair assessment, and raises the question: why does this happen?

Parents want their children to be healthy, happy and successful, and education is seen as a means to economic success. Education seems to offer a clear measure for parents – their children are graded in relation to other children, and they can judge how well their children are performing as developing economic citizens. The world judges children by their educational achievement, and there is a clear link between these education levels and their future financial success. There is no doubt that university (or, as they will have it in the US, college) education makes an economic difference to people: in broad terms, having a degree is worth a million dollars to any person who has one, and no parent can ignore that. If a child can succeed in education, then they are likely to earn more money, live longer and see their own children succeed.

As education is a way of improving the life chances of children, rich parents will try to buy a better educational experience. Richer countries spend more on education, and can have better educational outcomes. Despite that, more poor people have improved their social and economic status through education than through any other way. This has some interesting implications: if wealth could buy better education, then the educational gap between rich and poor would always increase as a result of ‘buying’ educational success, but it does not. The educational gap between rich and poor children is usually decreased in schools that do not charge fees. However, if there are high costs, this is not always true: in England the recent expansion in university education has benefited the better off, and this has decreased social mobility.

The comforting implication of this could be that schools improve poor people’s life chances because you cannot buy education or natural intelligence. The alternative explanation is more likely to be true: rich people (and rich countries) do not know what they are doing in education, and therefore no amount of money will buy them an education that preserves their social advantages – that is, until someone discovers how to create and sell educational advantage. In other words, education systems, schools and universities do not guarantee success. So parents are right to be unhappy about schools and universities – they do not necessarily deliver educational advantage.

Of course, education does not just occur in the formal education system of schools and universities. It occurs in homes, in social situations and in the daily work of every person. This vision of education occurring all around us might sound idealistic. Perhaps it should be thought of as a warning: if education is not good enough, then we are all responsible for that shortcoming: parents, peers, education systems and society itself.

The economy benefits from children’s education

Employers pay more to young people who have achieved highly because they believe they are more valuable. Companies, and the economy generally, appear to benefit from high educational outcomes. In business there is also a belief that the transfer of knowledge and information is an important part of making profits: we are in a knowledge or information society.

This knowledge society may or may not exist, but the indicators are that it does. Certainly the knowledge society is an accepted theory in the US, Europe and the OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) countries. If it is true, education is the next economic hurdle: how are we going to match the exponential growth in science and technology if we cannot improve the performance of people? This has led to deep concerns in some affluent countries about how to raise the educational level of their citizens. The UK, lagging behind other similar countries in the percentage of graduates in the workforce, simply set an artificial target of 50 per cent of all young people going to university. In the US, where this target has already been reached, many worry that the quality of degrees is becoming lower, and increasingly students find that there is the pressure to obtain postgraduate qualifications.

This panic (or appropriate action if you prefer) to raise the perceived level of educational achievement has led to simplistic visions that translate higher levels of education as equivalent to better economic performance. International think tanks propose visions of teaching changing, information society growing and the population becoming better workers through the development of education, leading to more advanced economies. The economic and educational dynamics of advanced economies must be more complex than this, though – perhaps – the underlying principles may be correct.

There are problems with such simple solutions. Even assuming that the number of students achieving degree standard can be increased (albeit slowly), the relentless advances in technology and science require higher and higher levels of expertise. For all the hype about improving education, simple models based on slow improvements in degree outcomes will fail to keep pace with changes in the world. The solution to this very real problem is not clear, but the necessity for greater efficiency, so that people can reach higher levels of educational attainment more quickly (and cheaply), is apparent. The lengthening time that education systems now take to prepare children for the modern world, and the growth of the post-work population, makes the current approach unsustainable: there would be too few people actually working. This is not the message that the education industry wants to broadcast: it continues to encourage society, business and individuals to spend longer and longer in formal, often full-time education. There is a very considerable incentive for educational institutions to promote such behaviour: they make more money. Societies are already facing problems in meeting the demands for more years of formal education and many advanced economies can indicate potential dangers if this trend is not curtailed...