![]()

Part 1

Contexts

![]()

1 Cities and urbanism

‘Cities and urbanism’ introduces how the city has been conceptualized, and the theoretical issues useful to photographers addressing issues relating to urbanism. First, I outline the principles of modernity and postmodernity that determine the historical contexts and circumstantial differences in the relationship between photography and the city. Second, I introduce the concept ‘city’ as providing a literal location within which to frame different cultural debates. Third, as this book’s main focus is the relationship between people and the city, I introduce a range of theorists who have framed ‘living’ in the city as social space – in particular Henri Lefebvre, Michel de Certeau and Edward Soja – and whose interdisciplinary approach is useful for the photographic exploration in later chapters.

Modernity/postmodernity

The project of modernity formulated in the 18th century by the philosophers of the Enlightenment consisted in their efforts to develop objective science, universal morality and law, and autonomous art according to their inner logic … The Enlightenment philosophers wanted to utilize this accumulation of specialized culture for the enrichment of everyday life – that is to say, for the rational organization of everyday social life.

(Habermas 1985: 9)

The age of modernity runs parallel with the growth of city expansion throughout the nineteenth century as a result of industrialization and the growing dependence on capitalism and production. Most commonly, the term ‘modernity’ is used to distinguish the ‘modern’ from the ‘ancient’, and from an era prior to the Enlightenment, which is understood as the pursuit of a rational social order and the desire for progress. It is associated with the increasing secularization of society that replaces the religious state and the assertion of scientific explanation replacing superstitious ‘primitivism’. In the nineteenth century, modernity incorporates mechanical production, industrialization and the development of consumerism. Increasing urbanization and consumption results in the consequent development of mass marketing, advertising and fashion and of new systems of communication (telephone) and of transport (underground rail networks) (Harvey 1990: 23). The invention of photography (1839) and its increasing appropriation for the promotion of state operations and capitalist expansion adds a further dimension, which I will discuss in Chapter 3. The positive aspects of modernity are the desire for a civilized and ordered society with a concern for humanity and justice, which become in practical terms the aspiration for improved social conditions. The negative aspects can be seen as the imperialist attitude to spreading these ‘civilizing’ influences across the globe, with no regard for the value of cultural difference. In addition, the rational attitude’s drive to assert a reasonable society, is seen as being increasingly instrumental in attempting to dominate nature, in exercising social power and in encouraging the divide between the disciplines of science, art and philosophy.

The terms ‘modernism’ and ‘modernist’ are used more specifically to refer to the products that arise from the cultural debates that characterize modernity – such as art, literature and architecture. Jürgen Habermas (1985: 5) describes aesthetic modernity as finding a common focus in the consciousness of the time, which is seen manifested in the drive to assert progress in a series of avant-gardes that each claim superiority over the one that precedes it (e.g. Futurism, Surrealism). In literature, the classic figure of modernity, and pertinent to this discussion, is that of the flâneur – epitomized by Charles Baudelaire and in the literary work of Gustav Flaubert. Baudelaire [1863] expresses the modernist aspiration to push forward, to move on from the past and to look for the quality that is particular to ‘the age, its fashions, its morals, its emotions’ (Baudelaire 1964: 3). He describes two characteristics of modernity that are of particular importance for a consideration of cities and photography: the relationship of the individual to the crowd in the metropolis, and the veneration of the ‘everyday’. He promotes the ‘modern’ artist as defining (his) vision by using subjects of everyday city life, rather than resorting to mythical or religious allegory in (his) search for eternal meaning (see also Box 4.1: The flâneur). As a consequence of the desire for rational order comes the drive to deliberately modernize urban living space, because modernist space is seen as a logical means to facilitate new ways of living. Modernist aspirations find validation in what is understood as urban progress and are made visible in concrete manifestations such as architecture and town planning. The idea that restructuring the physical city will ‘confront the psychological, sociological, technical, organizational and political problems of massive urbanization’ in order to progress social conditions, is an essentially modernist aspiration and is indicative of the modernist compulsion to progress (Harvey 1990: 25). Georges-Eugène Haussman’s rebuilding of Paris in the mid-nineteenth century is described as the quintessential example of this (see Box 1.1). Similarly, Le Corbusier’s revolutionary architectural vision is conceived in utopian terms [The City of Tomorrow, 1924]. He envisaged city planning on a grand scale to the extent, for example, of establishing different functional zones in his conception for the Ville Contemporaine (1922). However, as Fredric Jameson observes, modernist reconstructions of city space can fail to be realized in practical and human terms, sometimes only succeeding in translating an abstract logical system into a concrete form (Jameson 2009: 163). And Henri Lefebvre comments that Haussman’s reordering of the city reduced Paris from the human to the strategic management of people (Lefebvre 1991: 312). Utopian influences, such as Le Corbusier’s, can be compromised to the extent that they merely effect the appearance of an ideal. In the UK, the investment in visions of modernity and progress were realized in the high-rise estates built in the 1960s – the City of Manchester was typical in re-housing residents in estates outside the city in Wythenshaw, Langley, Heywood and Worsley. Many such developments subsequently proved to be failures in social terms, resulting in rapidly deteriorating environments, alienated communities, centres for crime, and eventual demolition in the 1980s and since.

Box 1.1 Symbol of modernity: Paris

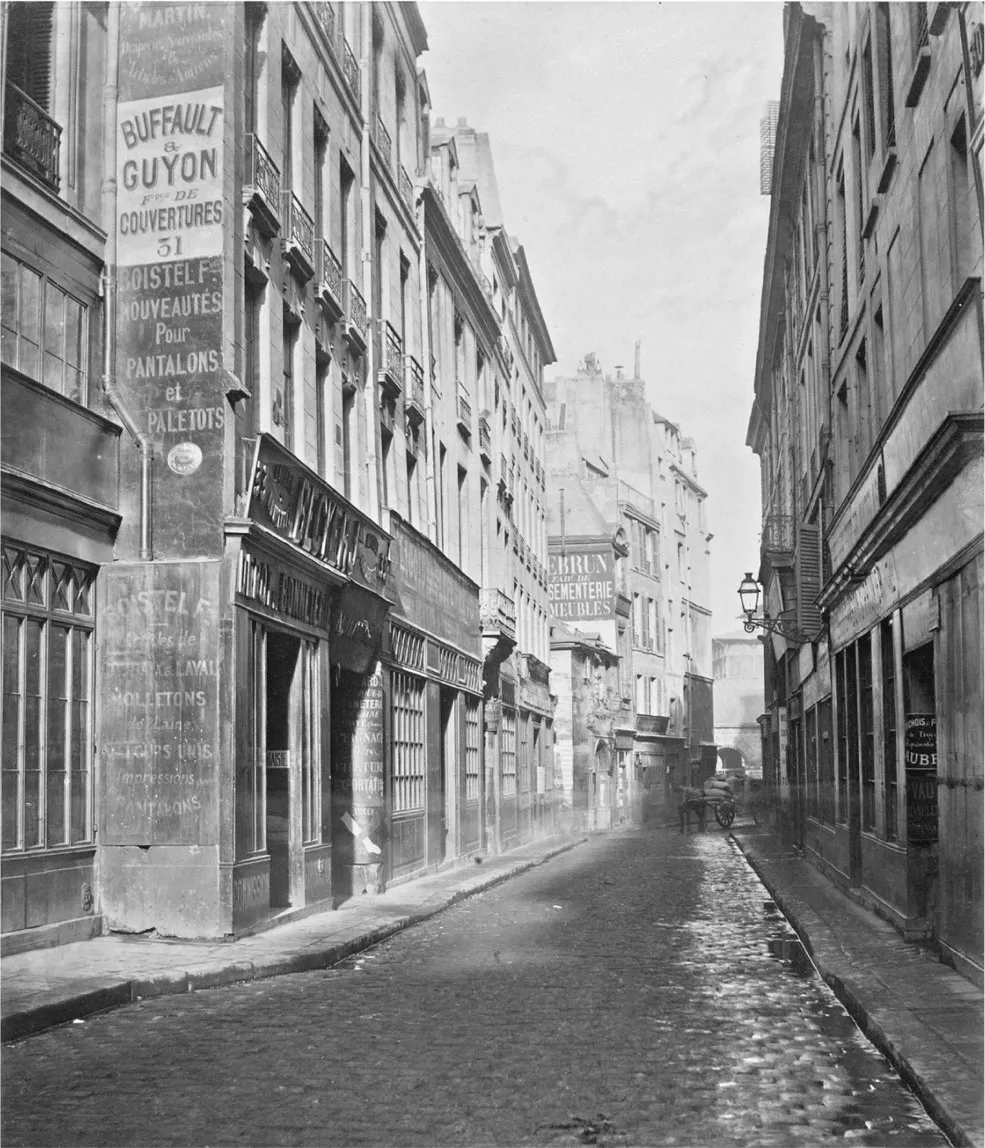

Figure 1.1 Charles Marville, Rue des Bourdonnais de la rue de Rivoli, Paris, 1865. Albumen silver print (31.1 × 27 cm).

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Something very dramatic happened in Europe in general, and in Paris in particular, in 1848. The argument for some radical break in Parisian political economy, life, and culture around that date is, on the surface at least, entirely plausible. Before, there was an urban vision that at best could only tinker with the problems of a medieval urban infrastructure; then came Haussman, who bludgeoned the city into modernity.

(Harvey 2003: 3)

David Harvey characterizes Paris as the ultimate exemplar of modernity, and of the ‘creative destruction’ that is associated with the implementation of its ambitions (Harvey 2003: 16). Following the uprising of 1848, Haussman was assigned the job of reconstructing Paris’s street system. He demolished large areas of Paris with the intention of creating something new and progressive. Harvey describes this process of rational progress as creating the myth that there was ‘no alternative to the benevolent authoritarianism of Empire’ (Harvey 2003: 10). This project, executed on behalf of government and promoted as being of benefit to the welfare and prosperity of the city, is an example of an exercise of institutional power made manifest in concrete reality. Walter Benjamin’s commentary [1935] on Haussman’s city planning describes the long perspectives down broad straight thoroughfares as a common nineteenth-century ideal and strategic move whereby ‘The institutions of the bourgeoisie’s worldly and spiritual dominance were to find their apotheosis within the framework of the boulevards’. Benjamin asserts that the true goal of Haussman’s projects was to secure the city against civil war: ‘Widening the streets is designed to make the erection of barricades impossible, and new streets are to furnish the shortest route between the barracks and the workers’ districts. Contemporaries christen the operation “strategic embellishment”‘ (Benjamin 2002: 11– 12).

Charles Marville (1816–79) was one of a team of photographers commissioned by Haussman in 1853 to record the city prior to its demolition and renewal. Held as a permanent record of the time in the Photothèque des Musées de la Ville de Paris, it is an early example of photography employed to produce a historical record for official posterity.

Postmodernity is generally understood to relate to the latter decades of the twentieth century – particularly the 1980s. There are no clear distinctions between modernity and postmodernity and, in many ways, conceptions of the postmodern depend on how we conceive modernity. For example, Jürgen Habermas [1981] interprets modernity as a project that is not yet fully realized and is suspicious of postmodernism because of its impulse to negate the positive and utopian aspects of the Enlightenment. He argues that what he calls the ‘project of modernity’ is not an era but an ideology. Similarly, Jean-François Lyotard’s notion of the postmodern condition [1979] is conceived as a dynamic that interrupts tradition – that prefaces modernism – in a cycle of tradition and anti-tradition. Habermas states that ‘modernity revolts against the normalizing functions of tradition’ and persists in the habit of ‘rebelling against all that is normative’ (Habermas 1985: 5). He goes further and suggests that postmodernism is the most recent version of modernism and just another ‘abstract opposition between tradition and the present’ (1985: 4). He suggests that instead of giving up modernity as a lost cause, ‘we should learn from the mistakes of those extravagant programs which have tried to negate modernity’ (1985: 12). In these terms, modernity is still very much alive. In discussing attitudes to postmodern ideas, he identifies the difficulty in distinguishing those who reject all that modernity stands for, from those who regret the decline of reason and the clear distinctions between different disciplinary enquiries, from those who welcome contemporary developments, which problematize reason, and changes in attitude such as the assertion of difference over the pursuit of universal meaning. Habermas’s argument with classifications of postmodernism highlights the problem with attempting to define its characteristics. All-encompassing terms, such as postmodernism, are problematic if not qualified by whose interpretation, and tend to be oversimplified and reduced to a few features which, in the arts and architecture, are taken to be paradox, irony, hybridity and self-conscious appropriations from popular culture and historical traditions.

Importantly, the condition of postmodernity, including its cultural products and associated ideas, represents a reaction to modernism’s vision of progress, absolute truths, rationalism and social order by giving consideration to difference and indeterminacy, the irrational and subjectivity. Modernism defined itself through the exclusion of mass culture, and postmodernism renegotiates high and popular forms of culture. Modernism is characterized by a utopian desire and commitment to radical change, and postmodernism – which questions the presumptions of modernism – by critique, demystification and the significance of difference. Jameson [1991] attempts to classify divisions in attitude by distinguishing between a postmodernism that is essentially anti-modern, and a modernism that is anti-postmodern, neither of which depends on a historic break but on ideological differences (Jameson 2009: 58–9). In this way of thinking, the condition of postmodernity can retain the ‘good’ attributes of modernity, whilst allowing for the many post-structural theories that have questioned the extremes of modernist assumption such as the new is good no matter what. If the utopian ambitions of high modernism (e.g. Le Corbusier’s City of Tomorrow) are recognized as being unrealizable, contemporary postmodernism may be described as merely the transference of modernist ideologies to reinvigorate contemporary processes with ‘fresh life’ (Jameson 1984: xx; 2009: 60).

As postmodernism is interpreted in very different ways, so too are its effects on society. Jameson’s analysis of the far-reaching implications of postmodernism and David Harvey’s suspicion of its most extreme forms provide two such examples, which attract criticism. And these perspectives are very different again from those cultural theorists generally referred to as postmodern (e.g. Jean Baudrillard, Paul Virilio), to whom I will return in Chapter 6. Both Jameson’s and Harvey’s scrutiny of postmodern culture incorporate analysis of aesthetic, cultural and political aspects, and are useful for a book that considers the exchange between the experience of urbanism and its depiction – Jameson’s evaluation makes direct use of cultural products such as photography to focus his socio-political assessment. His contention that culture is characterized by an interaction between political, social and economic elements is significant for a discussion of ideas visualized in photographs. And many of the photographic projects selected here address the consequences of ‘late capitalism’ and its effects.

The problem of postmodernism – how its fundamental characteristics are to be described, whether it even exists in the first place, whether the very concept is of any use, or is, on the contrary a mystification – this problem is at one and the same time an aesthetic and a political one. The various positions that can logically be taken on it, whatever terms they are couched in, can always be shown to articulate visions of history in which the evaluation of the social moment in which we live today is the object of an essentially political affirmation or repudiation.

(Jameson 2009: 55)

Jameson describes his book [Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, 1991] as an attempt to theorize the logic of cultural production that is symptomatic of late capitalist development, generally named ‘post-industrial’, but which he highlights as being ‘multi-national’.1 He situates his discussion within a Marxian historical materialism and in relation to Ernest Mandel’s analysis of the three stages of capitalism that develop with global expansion: market capitalism, monopoly capitalism and late multi-national capitalism [Mandel, Late Capitalism, 1975]. He draws parallels between these stages of capitalism and changes in the city, for example: classical market capitalism with Haussman’s geometrical ordering of urban space, and late capitalist expansion in the city with the disorientation of individual experience (2009: 410–13). As a Marxist critic, Jameson is concerned with issues of class structure, modes of production and the difficulties in organizing political action in response to new social formations. His discussion raises questions for living and working in the city in the face of multi-national societies dominated by new technologies, and the development of a form of commodity production that satisfies the needs of the consumer, whilst simultaneously driving material desires. Jameson emphasizes multiple perspectives for explanation of the postmodern phenomenon and compares a number of theoretical possibilities – a method he refers to as ‘transcoding’ (394). He thereby contributes an interdisciplinary approach to cultural critique, which characteristically focuses on what is problematic or what subverts the norm, rather than attempts to find a ‘truth’ or a resolved position. However, Jameson’s method of reference to diverse discourses attracts the criticism that such wide-ranging analysis does not give sufficient focused address to key postmodern concerns such as agency or ...