![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

AIMS

Our book is centrally concerned with a set of issues that we believe to be critical in understanding the contemporary world. Our principal focus is on the geographies of economic activity or the various ways in which people strive to make a living. The idea of making a living points to the centrality of economic life in determining not just whether one is rich or poor but also – and more fundamentally – whether one thrives or struggles to live in the global economy.

The subject of our book is two-fold. On the one hand we want the reader to learn something about contemporary economic geographies and particularly the contrasting economic fortunes of different people and places. Why is it, as we start the new millennium, that the geographies that we portray in this book continue to be characterized by massive inequalities of economic wealth and opportunity? Why is it that certain established economic centers – such as the City of London – continue to thrive while others, including neighborhoods in the shadow of the City itself, exhibit stagnation and decay? Or why is it that while cities in China and India grow at break-neck speed, rural communities in those countries lack basic necessities? This book then is partly about addressing such questions. We aim to highlight enduring features of the world's economic geographies as well as their shifting and volatile nature. The City of London's long success as a global financial center on the one hand, and the rise of places like Mumbai, Shanghai and Dubai as relatively new financial centers that might one day rival London and New York, on the other.

But the book is also about how we study these economic geographies. In short, we have sought to introduce both economic geographies and economic geography as a discipline or as a body of academic knowledge. We see these twin objectives as closely linked. Our understanding of the economic geographies of the global economy is very heavily conditioned by the changing ways in which we come to define and represent our object of study. The theories and frameworks we use to study the world heavily condition what counts as economic geography and what matters in terms of presenting economic geographies. And in turn, changes in the dominant ways in which we represent and study the economy are shaped by the changing material geographies of economic life.

Our book appears at a time in which some have seen the discipline of economic geography as a rather troubled one. Various commentaries have expressed concern about the dwindling numbers of graduate students attracted to the field and, more generally, about the way in which matters economic have come to be displaced by cultural concerns, deemed more generative of new theories and ideas. Such concerns have given rise to debate about how best to revitalize the study of economic geographies. Should economic geographers embrace the cultural turn and find common ground with scholars in allied fields, such as sociology, anthropology and cultural studies? Or should economic geographers stick to their traditional concerns and forge new links (or reforge old links) with the ‘high ground’ of economics? Certainly the works of a number of high profile economists such as Michael Porter and Paul Krugman have helped to raise the visibility of the ‘new economic geography’ but the limelight is not without its costs.

Despite much recent introspection, and not a little selfdoubt, we think there are at least three good reasons to expect economic geography to remain a vital field of study. The first is an historical one – from the pioneering location theories of Christaller, Losch and Weber considered in Chapter 2, through its role in the Quantitative Revolution of the 1960s, to its central position in the political economy approaches of the 1970s considered in Part III, economic geography has often been in the vanguard of change within the discipline of geography. The second is the significance and vibrancy of contemporary debates. These concern foundational questions such as the distinctiveness of the ‘economic’ and especially its relationship to ‘culture’ and ‘nature,’ questions of theory and method and the political and policy implications and relevance of contemporary economic geography research. The discussions around these issues have been a fertile source of new ideas and directions. These are the sorts of issues that are central to our book. The third reason is economic geography's concern with questions of pressing real-world significance. At the current time these include: the nature and effects of globalization and neoliberalism; the nature, extent and trajectory of economic inequalities at regional, national and global scales; the shift to a knowledge based economy; and the concern with global political-economic uncertainty and risk. In short we hope that this book illustrates the value of a geographical approach to the study of economic matters and economic life.

The animated nature of recent debates suggests that no single approach to economic geography is currently hegemonic. Yet introductory textbooks in this field commonly fail to reflect its range and diversity. The field is strangely polarized – at one end traditional texts stick with the location theory/spatial analysis tradition, paying scant attention to recent theoretical developments. At the other pole books rooted in the ‘new economic geography’ tend to be pitched at a graduate/research oriented audience and are largely dismissive of traditional work. Our book seeks to encompass the ‘missing middle’ by including traditional approaches, albeit from a critical perspective, while at the same time providing a thorough and accessible examination of the concerns, methods and approaches labeled as the ‘new economic geography.’ The book, and the underlying rationale for its structure and scope, rests on the need for a more pluralistic economic geography, one which advances an explicitly eclectic sensibility rather than advocating a dogmatism that either critiques the ‘faddish’ nature of the ‘new economic geography’ or alternatively, dismisses all that came before the mid- 1970s as redundant and irrelevant to understanding contemporary economic geographies. While anchored in a perspective that emphasizes the social and relational – and thus inherently political – nature of economic geographies, the text also seeks to highlight the contemporary resonance and value of traditional approaches.

MAIN THEMES

This book is designed, first and foremost, to provide an introduction to economic geography by establishing the substantive concerns of economic geographers, the methods deployed to study them, the key concepts and theories that animate the field, and the major issues generating debate. In this sense the book is as much about approaches to economic geography as it is about changing economic geographies on the ground. Throughout the text we emphasize the contextual nature of different approaches, relating developments in the field to broader intellectual currents as well as to concrete changes in the nature, scope and spatial extent of economic activities. Deciding how to structure such a book is not a simple task. A strictly chronological tour through different approaches would likely fail to sustain interest other than for those with an interest in disciplinary histories. We suspect that most of our readers are more interested in what the latest work can tell them about economic geographies. Any attempt to provide encyclopedic coverage would likely suffer the same fate, providing a rather shallow appreciation. Yet the diversity of the field militates against an alternative thematic framework that might seek to combine insights from traditional and newer approaches. In order to maintain coherence and unity while at the same time promoting an eclectic sensibility the book avoids structuring the text around a single theme. Instead, the organizing framework is a looser heuristic one that focuses on three key relationships. These are:

- The relationship between geographic fixity and mobility of economic forms and practices.

- The relationship between economic actors, strategies and identities and the structures/networks within which they are embedded.

- The spatial nature of economic practices and forms and the relationship between economic processes and practices at different spatial scales.

By adopting this framework, we hope to offer students and their instructors fresh ways of thinking about the geographies people create as they go about trying to secure their lives and make a living in the global economy.

The front cover of the book shows an artistic image created from photographs of shipping containers. Shipping containers are standardized 20 foot or 40 foot long steel boxes used to ship an enormous variety of raw materials (copper ingots to coffee beans), and manufactured parts and goods (mp3 players to machine guns) across oceans and continents. They are intermodal, meaning that in addition to traveling on container freight ships, they can be moved by rail and by road. An individual can order a container to be picked up from an inland location in one continent and delivered to an inland location in another. The contents of the container are untouched as it moves from truck to train to crane to ship to crane to truck. There are over 8,800 container ships plying the world's oceans, with a total capacity of over 12.5 million TEUs or 20 foot equivalent units. It is estimated that in 2008 alone, container throughput globally was over 150 million TEUs.

Shipping containers such as those shown on the cover might seem to epitomize mobility. They have certainly revolutionized the shipping industry since their introduction about 50 years ago, permitting smoother, faster and cheaper long distance transport. Their role in the increasing volume of goods that move across borders each year has been significant. However, much as they signal movement, containers bring with them demands for all sorts of fixed investments. They require ports that have deep-water docks to accommodate large container ships, reinforced quays to handle stacked containers, specialized cranes, and rail and truck transfer facilities. Container ports are hubs in transportation networks that function on the basis of enormous investments in fixed capital. The mobility of the container is dependent upon the fixity of port infrastructure and, not coincidentally, upon the displacement of large numbers of dock workers. The geography of trade routes is underlain by the geography of ports. This is one way in which we can see the centrality of the mobility–fixity relationship in understanding economic geographies. New ports are created only with enormous investments such that the geographies of container transportation are channeled in quite particular ways. The mobility of the individual container is shaped and constrained by a fixed infrastructure whose ‘sunk costs’ lend it considerable stability over time.

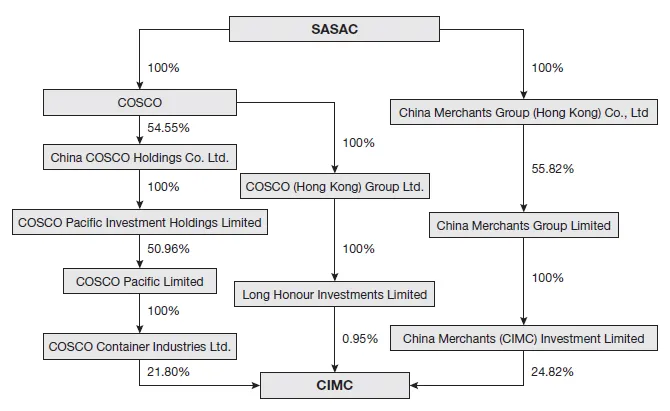

Yet this is only one of a number of aspects of mobility and fixity that underpin the shipping container. For example, the container itself is manufactured from coiled steel by workers who use stamps and presses and welding equipment to construct the boxes, install wooden floors on the interior, paint the containers and add door hardware. Most containers are made in Asia, and the majority in the People's Republic of China. The largest manufacturer of containers is the China International Marine Containers Group Limited (CIMC). Their 12 factories in China, employing over 40,000 people, account for about 40 percent of the world's annual supply of new containers. The production of containers then can be seen as entailing the convergence in time and space of a set of tangible inputs (steel, electricity, labor – much of it migrant labor from other parts of rural China) and less tangible inputs in the form of international standards on the construction of containers specifying their size, strength and so on, as well as market knowledge and intelligence concerning trends in the shipping industry and likely demand for new containers. The economic actors involved are diverse, and range from those directly producing the containers – the workers, the managers, the salespersons – and those only tangentially connected such as the buyers, the brokers, the financiers, the designers and the regulators. In addition, we could consider the firm an economic actor. On closer inspection the firm is not singular, it comprises complex intersecting networks of actors. For example, CIMC has two major shareholders: a British Virgin Islands based subsidiary of the giant COSCO Group (a Chinese grouping of shipbuilding and logistics companies) and the Hong Kong based China Merchants Group, a conglomerate that traces its roots to 1872. Complicating matters further, the entire structure is overseen by the Chinese Government's State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) (Figure 1.1).

The corporate architecture of CIMC speaks to the rapidly changing geography of Asian stock exchanges and financial services, as much as it speaks to the extraordinarily dynamic nature of China's manufacturing sector. Specialized knowledge of financial services and products, risk management strategies, and management expertise located in Hong Kong and Shenzen, are important factors in accounting for the shareholding structure of CIMC. However, the vast majority of CIMC's employees work on the factory floor. It is quite likely, given the regional patterns of employment and unemployment in present day China, that many of these workers have migrated to the coastal regions in search of work. Thus in this example, however brief our sketch, we can discern how very different lives, knowledges, materials, institutions and locations are linked together and differently embedded in the production of this one commodity: the shipping container.

Figure 1.1 Ownership of China International Marine Containers Group Limited

Source: CIMC (China International Marine Containers) 2010

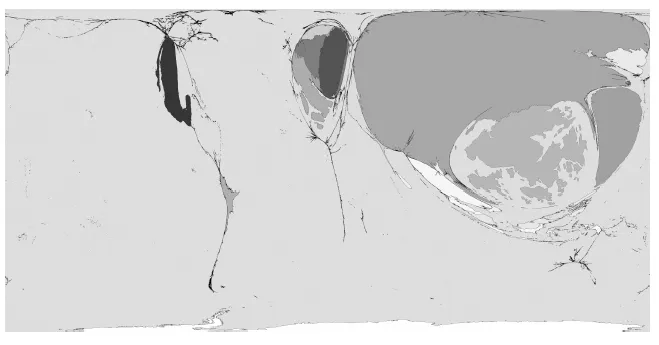

If we zoom out to consider the big picture of global trade that has been driving the manufacture of new shipping containers in Asia, we see a relationship between the debt fueled demand for cheap manufactured goods, particularly in North America and also in Europe, and the concomitant rise of manufacturing in Asia – a trend that slowed with the financial system failures that began in the US in late 2008. Shipping mediates demand and supply as every day millions of containers cross the oceans and the continents, their contents loaded at factory gates in China and bound for the shops of North America and Europe (Figure 1.2). This global economic geography of demand and supply, of massive regional differences in labor costs and in disposable income between Asia and North America and Europe, frames a whole series of other contributory geographies. Ongoing deforestation in remote parts of China's interior regions – such as Yunnan province – to supply plywood to make the interior floors of the steel containers is related to these global patterns. That migrants are leaving their farms and their families to seek work in the booming coastal cities of China is also a related development. Diverse and maybe even contradictory economic processes and practices at different spatial scales are bound up with one another in complex ways.

Figure 1.2 Toy exports

Note that this is a cartogram. Each country's size is proportional to its share of worldwide net exports of toys (in US$). Net exports are exports minus imports. Thus, this is a different kind of map than that which represents countries based on their land area. The shading is just to assist in identifying and distinguishing the countries. There are several other cartograms used in this book.

Source: Worldmapper 2010 © Copyright 2006 SASI Group (University of Sheffield) and Mark Newman (University of Michigan),www.worldmapper.org/.

Developments in containerization and transportation more generally, along with rapid changes in telecommunications, have been seen to herald the birth of a truly global economy in which competition allows for the consumption, by some of the world's population at least, of a dazzling array of products from economically booming distant places. So for some there might be much to laud about the globalization of economic activity. However, our next example of global traffic flows serves to sharpen the point that mobility and fixity can be combined in quite detrimental ways. In August 2006, residents of Abidjan, in the West African country of Cote d'Ivoire (Ivory Coast) awoke to find their eyes burning, heads aching, breathing labored and stomachs cramping. A distinctive odor indicated that their ills were traceable to pools of black sludge that had been dumped by trucks in 14 locations around the capital city under the cover of night. In the words of the journalist Sebastian Knauer and colleagues:

The worst is when it ra...