1

An Introduction to Problem-based Learning

Terry Barrett and Sarah Moore

Introduction

Problems have always mobilised and stimulated thinking and learning; they energise our activity and focus our attention. When problems are experienced as relevant and important, people are motivated to direct their energies towards solving them. It is exactly these energising and curiosity-inducing dimensions of problems that form the basis and rationale for using problems in teaching and learning. Although problem-based learning has existed since the dawn of time, in higher education contexts we can trace problem-based learning (PBL), as a total approach to student learning, to the 1960s in North America. The basis of PBL consists of creating real-life problems for students to work on in small teams (Barrows, 1989). Now, in the 21st century, people across the globe in diverse disciplines and professions are using PBL. While some people use PBL in systematic, integrated ways, using shared methodologies across whole programmes and institutions, others use PBL in particular modules or units of a programme.

Many teachers in higher education are now highly experienced in the design and use of problems and are comfortable with the PBL methodologies that have been part of the higher education landscape for many years. However, many others are still new to the concept of PBL. This textbook brings a series of new voices to the PBL literature along with the input of people who have been practising PBL for several decades. Whether you are experienced in or are new to PBL, we believe that this mix of voices will help you to explore the following questions:

• What is the value of PBL?

• What new approaches to PBL have teachers in higher education been practising?

• How can PBL be used to energise and develop exciting and effective learning environments in higher education?

• How can we revitalise our PBL initiatives?

It is timely, given the history and the popularity of PBL, to problematise problem-based learning; indeed, it would be a contradiction in terms not to treat PBL itself as a problem. Experienced PBL practitioners need to refresh, revitalise, adapt, and keep looking at new ways of using PBL in higher education, and the voices of educators who are still new to PBL can help this form of pedagogy to develop and enhance the impact it can have on student learning.

Chapter Overview

For those who are new to PBL, this chapter will help to familiarise you with some of the key ideas, values, and principles associated with PBL, and for those of you who are familiar with PBL, this chapter will be useful in mapping out the key concepts and principles that will be explored in more detail in other parts of this text.

In order to fulfil these aims, this chapter will:

• define problem-based learning as a total, six-dimensional approach to higher education;

• outline how these key dimensions of problem-based learning will be explored in the book;

• show what the PBL tutorial process can look like in practice;

• list the success factors for PBL initiatives;

• provide an overview of the book.

Problem-based Learning as a Total, Six-dimensional Approach to Higher Education

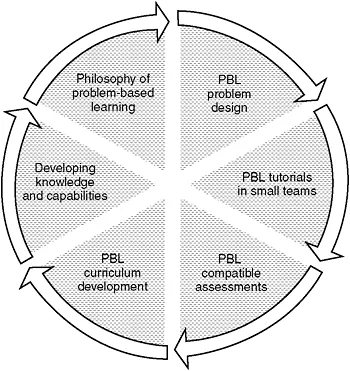

The classical definition of problem-based learning is: “the learning that results from the process of working towards the understanding of a resolution of a problem. The problem is encountered first in the learning process” (Barrows & Tamblyn, 1980, p. 1, our emphases). Problem-based learning focuses on students learning, not on teachers teaching. It has often been defined as “a total approach”, not just a teaching technique or tool. We argue that to revitalise our practice of PBL we must work on each of the six dimensions of PBL and their interrelationships. Our conception of PBL as having six dimensions is central to this book. Six key dimensions of PBL are presented in Figure 1.1.

Dimension 1: PBL Problem Design

Many teachers use problems to stimulate learning. However, a key characteristic of PBL is that problems are presented to the students at the start of the learning process rather than after a range of curriculum inputs. The PBL problem can be a scenario, a case, a challenge, a visual prompt, a dilemma, a design brief, a puzzling phenomenon, or some other trigger designed to mobilise learning.

Schmidt, van der Molen, te Winkel, and Wijnen (2009) highlight three key roles of problems in PBL curricula, namely:

1. increasing levels of curiosity in domains of study;

2. experiencing relevance of the curriculum as problems are perceived as pertinent to future professions; and

3. integrating learning from all curriculum components, e.g. PBL tutorials, practice placements, lectures, and skills training.

It is important for us, as PBL practitioners, to continually find new ideas for selecting or designing relevant, motivating, challenging, interesting, multi-faceted, and up-to-date problems for our students.

Chapters That Will Help You to Explore PBL Problem Design

Design processes involve an interaction with ideas, stakeholders, and media, and the chapters in Part I of the book provide material for refreshing the design of problems in your own PBL initiatives. Part I of this book provides a range of examples of problems used in PBL initiatives. We emphasise the importance of giving the design of effective problems the serious and creative energy it deserves as a key success factor in PBL initiatives (Gijselaers & Schmidt, 1990). Chapter 2 provides some illuminative concepts for thinking about designing problems in different media and practical strategies for how to design effective problems. The importance of involving clinicians or other professionals and students is stressed in Chapters 3 and 4, respectively. Chapter 6 focuses on sharing recent research and practice on video, role-play, and compare-and-contrast problem types.

Dimension 2: PBL Tutorials in Small Teams

At the heart of PBL initiatives are small teams of students with tutors working on problems in tutorials (Silén, 2006). Often, there are about five to eight students in a tutorial team with one tutor. Where there are fewer resources, one teacher can act as a roaming tutor between two or three teams. Teams usually work together around a table with some way of capturing group discussion (e.g. a whiteboard). In the PBL tutorial, knowledge is not a process of reception, but rather a process of construction, where students generate knowledge together as they link prior learning and experience to new learning (Ausbel, 1968). The importance of the social environment of the PBL tutorial in developing individual understanding is emphasised by Savery and Duffy (1995, p. 32):

The functioning of the PBL tutorial is underpinned by three major principles of social constructivism that connect learning theories to problem-based learning:

1. Elaboration of knowledge at the time of learning enhances subsequent recall (Norman & Schmidt, 1992).

2. Students can learn more with capable peers than on their own (Harland, 2003; Vygotsky, 1978).

3. Learning is a dialogical process based on thought-language (Barrett, 2001; Freire, 1972).

Chapters That Will Help You to Explore the Small-Team Nature of PBL Tutorials

Chapter 9 provides ideas and strategies for maximising the potential of the PBL tutorial for learning together. The role of the tutor in developing the information literacy of the PBL students in the tutorial setting is highlighted in Chapter 10. Chapter 16 focuses on tutor development and strategies for inspiring and effective tutorial facilitation.

Dimension 3: PBL Compatible Assessments

Assessment drives student learning (Biggs, 2003). As well as designing challenging problems and facilitating effective tutorials, assessments need to be designed in such a way that they align with:

• learning outcomes;

• the development of student capabilities; and

• the problem-based learning process.

Chapters That Explore the Ways in Which Assessment Can Align and Integrate with PBL Practice

Chapter 13 provides us with ideas and examples that stimulate us to think of the ways that assessments can be used to promote student capabilities. Chapter 14 explores different ways that triple jump assessments can be designed to align assessment and learning in PBL curricula.

Dimension 4: PBL Curriculum Development

PBL curriculum development is a major, multidimensional change management project (Conway & Little, 2000). The core of a PBL curriculum is students working on PBL problems in tutorial teams. Other curriculum inputs, e.g. lectures, resource sessions, practice placements, research seminars, and skills training need to be planned and sequenced in the curriculum in order to create an integrated PBL curriculum (Kolmos, 2002).

Chapters That Focus on Developing a PBL Curriculum

In Chapter 15 crucial considerations for curriculum planning and capac...