Chapter 1

Introduction

While individual popular press articles are imperfect indices of the complexities and contradictions of a broad and diverse culture, they can be important and resonant snapshots of the state of play on key issues such as gender and class. In this context, I want to reference two headline pieces published in late 2006 as I worked on this book. These articles appeared in two of the top three most well-read American daily newspapers: USA Today and The New York Times (and in the case of the latter on the front page on Christmas Eve). The first reported on the growing number of American Christian women (of various denominations) choosing to cover their hair and don “modest dress.” In “Traditional Living Takes Modern Spin,” Elizabeth Weise noted that the Internet had been adopted by many such women to shop for conservative clothing and head coverings and to affiliate with like-minded women via discussion groups. Weise observes in passing that most of her interview subjects for the piece sought the permission of their husbands before talking to her.

The second article, “Scant Progress on Closing Gap in Women’s Pay,” summarizes a recent set of economic data and opens with a startling observation about gender-based income equity regression:

Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, women of all economic levels—poor, middle class and rich—were steadily gaining ground on their male counterparts in the work force. By the mid-1990s, women earned more than 75 cents for every dollar in hourly pay that men did, up from 65 cents just 15 years earlier.

Largely without notice, however, one big group of women has stopped making progress: those with a four-year college degree. The gap between their pay and the pay of male college graduates has actually widened slightly since the mid-1990s.1

Holding these two articles in mind as anchor points for some of the pleasures and problems currently associated with contemporary American middle-class femininity, I want to underscore the necessity of probing the links between media representation and social behavior and start to build the case that any significant engagement with the popular culture landscape of the last 15 years requires wrestling with the concept of postfeminism.

What a Girl Wants? is about a popular culture that has just about forgotten feminism despite constant, generally negative invocations of (often anonymous) feminists. To the extent that she is visible at all, the contemporary feminist appears as a narcissistic minority group member whose interests and actions threaten the family and a social consensus that underwrites powerful romanticizations of American “community.”2 By caricaturing, distorting, and (often willfully) misunderstanding the political and social goals of feminism, postfeminism trades on a notion of feminism as rigid, serious, anti-sex and romance, difficult and extremist. In contrast, postfeminism offers the pleasure and comfort of (re)claiming an identity uncomplicated by gender politics, postmodernism, or institutional critique. This widely-applied and highly contradictory term performs as if it is commonsensical and presents itself as pleasingly moderated in contrast to a “shrill” feminism. Crucially, postfeminism often functions as a means of registering and superficially resolving the persistence of “choice” dilemmas for American women. From the late 1990s renaissance in female-centered television series to the prolific pipeline of Hollywood “chick flicks,” to the heightened emphasis on celebrity consumerism, and the emergence of a new wave of female advice gurus/lifestyle icons, the popular culture landscape has seldom been as dominated as it is today by fantasies and fears about women’s “life choices.”

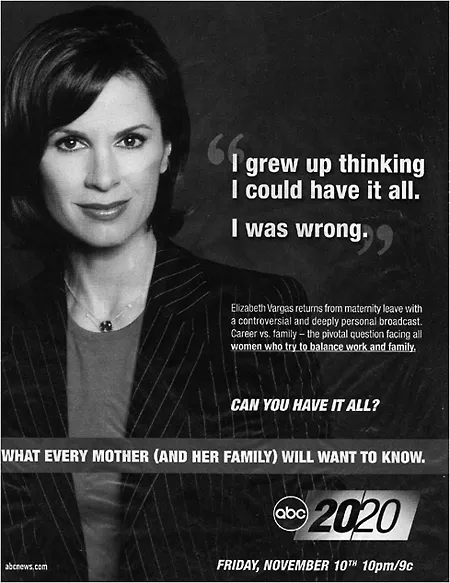

Emblematic of the kinds of stories about women’s lives that currently predominate in popular culture was the controversial case of Elizabeth Vargas, the first woman to anchor an American evening newscast since Connie Chung. Vargas, who in fact initially shared the role as anchor of ABC’s World News Tonight with Bob Woodruff, found herself a solo anchor when Woodruff was seriously injured covering the war in Iraq. In May 2006 Vargas suddenly resigned from her post, citing the demands of the job and their impact on her family and in particular her pregnancy. “For now, for this year, I need to be a good mother,” Vargas was quoted in a Washington Post article exploring the reasons for her departure and its significance for public views of women in the workforce.3 However, a number of commentators (including National Organization of Women President Kim Gandy) expressed skepticism about Vargas’ account, deeming it a face-saving “cover story” for the reality that Vargas had lost out in a power play by Charles Gibson, the longtime ABC journalist who reportedly said he would quit the network if he was not named sole and permanent anchor. Such commentators questioned the timing of Vargas’ decision, observing that her personal circumstances had not previously kept her from taking on high-profile and demanding journalistic roles, and questioning why it appeared automatically to be necessary to rethink Vargas’ role once she held a sole rather than shared position. Whatever the truth of the story, what is indisputable is that ABC and Vargas subsequently sought to use public interest in her case as a selling point for Vargas’ relaunch as a co-anchor of the magazine pro-gram 20/20 in which she appeared as the focus of a segment ostensibly exploring the difficulties of the “work/life balance” for women.

Figure 1.1 In 2006 the professional and personal situation of ABC News anchor, Elizabeth Vargas, was framed as an exemplary postfeminist narrative.

Among other things, this book seeks to move the issues so often posed in the simplistic terms of a feminized “work/life balance” dilemma toward fuller scrutiny, and much of the analysis here considers the distorted renditions of choice that permeate postfeminist fiction. By pinpointing the pervasiveness of postfeminist shibboleths about life, work, marriage, and motherhood, I hope to identify the kinds of identities and experiences that are withheld from postfeminist display practices and to argue for a more capacious view of women’s lives, interests, and talents than is generally fostered by the current culture. One of the signature features of postfeminist culture is the way in which it extends and elaborates “backlash” rhetoric, producing discursive formulations that would often seem resistant to feminist critique. Nevertheless, I hope to show that feminist tools of analysis are effective in reading postfeminist texts, thereby countering the postfeminist presumption that feminism is dated, irrelevant, and inapplicable to current culture.

It is important to acknowledge that the analyses undertaken here are in no way exhaustive and the chapters that follow are offered in some respects as “soundings” of a postfeminist culture. What I do not do in this book is provide an account of the ways in which individual consumers negotiate the content of postfeminist representations (as many surely do) nor do I investigate the potential “open spaces” that may be available in some postfeminist texts to facilitate spectatorial negotiation. The reason for this is that I believe that the overwhelming ideological impact that is made by an accumulation of postfeminist cultural material is the reinforcement of conservative norms as the ultimate “best choices” in women’s lives. In media studies scholarship irony and self-reflexivity are conventionally attributed with the power to neutralize conservative ideological representations, but the political efficacy of postfeminism may necessitate reconsideration of such precepts. Recognizing the polysemic nature of all texts, I would emphasize that the readings here follow a particular path that reflects a feminist analytical commitment. I do not believe that postfeminism inevitably or exclusively correlates to the re-energizing of patriarchal agendas and standards of value. However, while I fully acknowledge that there are many kinds of postfeminism (as Sarah Projansky among others has argued) some kinds are more predominant, perhaps especially in a culture in which critical literacy is so devalued.4 While postfeminism may be politically ambidextrous in some contexts, the majority of its fictions seem to operate in support of a larger political trend toward the undoing of US democracy and the suppression of the kind of vibrant, full, and questing subjectivities that a healthy democracy both fosters and draws upon.

Postfeminism attaches considerable importance to the formulation of an expressive personal lifestyle and the ability to select the right commodities to attain it. In this book I seek to challenge cultural bromides that reinforce the importance and value of consumerist notions of taste, glamour, and serenity and to analyze the nature of a platitudinous postfeminist culture that continually celebrates reductions and essentialisms as explanatory keys for women’s psychological and social health. As I will show, postfeminism fetishizes female power and desire while consistently placing these within firm limits. One of the ways I will pinpoint this dynamic is by drawing upon the work of commentators like Ariel Levy who have shown how the female sexual desire which seems so unbounded and expressive everywhere in the popular culture landscape, often operates merely in mimicry of sexist codes of exploitation.5 Postfeminism withdraws from the contemplation of structural inequities fostered by feminism, putting forward diagnostics of femininity that take the place of analyses of political or economic culture. It achieves this, in part, by relentlessly stressing matrimonial and maternalist models of female subjectivity.

Any attempt to precisely pinpoint the onset of a postfeminist era will lead to a receding historical horizon. As Lois W. Banner has observed, “Women have consistently protested against their situation, and this rebellion has led contemporaries in every decade since the 1920s to proclaim that women have attained equality and that feminist goals have been achieved.”6 If feminist interventions have long tended to be declared successful and unnecessary on arrival, it is nevertheless the case that popular culture in the 1990s and 2000s has been particularly dominated by postfeminist themes and debates. This book holds up a mirror (inevitably one with a somewhat refracted view) to the contemporary female subject who finds herself the recurrent target of advertisers, centralized in commodity culture to a largely unprecedented degree at a time when Hollywood romantic comedies, chick-lit, and female-centered primetime TV dramas compete for her attention and spending power. Across the range of the female lifecycle, girls and women of every age are now invited to celebrate their empowerment in a culture that sometimes seems dedicated to gratifying their every desire. This book asks why, at a moment of widespread and intense hype about the spectrum of female options, choices, and pleasures available, so few women actually seem to find cause for celebration. Why does this period feel so punishing and anxious for so many?

One of the ways in which I explain the omnipresence of postfeminist identity paradigms in the current popular culture environment is by emphasizing how such paradigms frame the search for self with an attendant assumption that feminism has disturbed contemporary female subjectivity. Over and over again the postfeminist subject is represented as having lost herself but then (re)achieving stability through romance, de-aging, a makeover, by giving up paid work, or by “coming home.” (Indeed, one of postfeminism’s master narratives is that of “retreatism,” which operates as a powerful device for shepherding women out of the public sphere.) Popular culture insistently asserts that if women can productively manage home, time, work, and their commodity choices, they will be rewarded with a more authentic, intact, and achieved self. Such postfeminist responses to identity crisis respond specifically to the conditions of degradation of the American self fostered by “New Economy” market fundamentalism, state-supported (and sometimes state-sponsored) assaults on the environment, intense anti-immigration rhetoric in a nation that still celebrates itself as a global beacon of hope for the downtrodden, the withering role of state care for the vulnerable, and various perversions of democracy that have flourished in recent years and that take shape (among other ways) in a strategic confusion between wars fought for economic interest and those fought for democracy, justice, or human rights.

As I will show, postfeminism retracts the egalitarian principles of feminism (even if those principles were in some ways faulty or if their egalitarianism was never quite complete), taking hold as an ideological system in a period in which democratic equity may be seen to have curdled into entitlism. At different points in this book I suggest that the ideological precepts of postfeminism mesh well with a system of political and economic extremism and that postfeminism significantly emerges in the context of powerful antidemocratic tendencies and at a time when “inequality rose in a period of increasing prosperity, with the added riches going much more to the haves than to the have-nots.”7 The United States entered the twenty-first century with the sweeping into office of a president who more or less openly championed the interests of the wealthy. Recent research shows that economic mobility (the signal feature of the American Dream) has been arrested in a number of demographic categories and the rich now enjoy strikingly disproportionate benefits of health care, lifespan longevity, and access to education in comparison to the general population.8

Bearing in mind, then, the increasingly open celebration of wealth and privilege in America, much of the discussion in this book is framed against a social backdrop that stresses the primacy of a personal aesthetic system and an elaborated relationship to family and home even as the economic and social pressures on family life intensify for the great majority of Americans. A significant concern is with the continuities and discontinuities between representation and lived reality and in my analyses I seek to balance my readings of fictional texts with sociological and economic data. For instance in Chapter 4, I examine the “enchantment effect” of so many contemporary romantic comedies which suggest a heroine will be unlocked/relieved from her current state (often as a working woman). But I also document the proliferation of other forms of cultural representation that have highlighted the figure of the working woman, and then move to examine how and why such images acquire cultural traction. In considering how certain female job roles have become overrepresented and fetishized even as postfeminist culture exhibits a persistent distrust of the “working woman,” particularly if she is an executive, I am less concerned with producing a totalizing account than with mapping the paradoxes which so often emerge in postfeminist culture.

Postfeminism both informs and is informed by a cultural climate strongly marked by the political empowerment of fundamentalist Christianity and regnant paradigms of commercialized family values.9 Notably, it has flourished in a period of American history in which, as Henry A. Giroux has argued, “The corporate state unabashedly began to replace the last vestiges of the democratic state as the central principles of a market fundamentalism were applied with a vengeance to every aspect of society.”10 In postfeminist representations some of the most crucial institutions of democratic culture are understood to have entered a kind of twilight and there is often an implicit engagement with the prospect of long-term downward mobility for the middle class. In various ways postfeminism stifles mobility, favoring constraint and the acquiescence to norma-tive models of identity even while hyping aspirational consumerism. In popular film, plot devices for staging this entail the encoding of discovery, adventure, and a staunch commitment to “choice” in forms such as the resignation from work (as in Kate & Leopold, 2001), the discovery of an aristocratic family background that automatically confers wealth and privilege on an “average” young woman or girl (as in The Princess Diaries, 2001), or the formula of the ready-made family which leads a “career woman” to discover that her truest vocation is stay-at-home parenting (as in Raising Helen, 2004). Ideologically central to the contemporary chick flick is the concept of “destiny” which recurs in innumerable recent romances. Asserting a need for order in the face of an apparently random reality and a general desire to evade ambiguities related to identity and intimacy, the films consistently “discover” that actually fate has it all worked out. With “destiny” operating as an organizing principle and themes of true love and the propitious/serendipitous meeting predominating, a number of films have gone so far as to suggest that the ideal romantic partner in adulthood is a childhood playmate grown up (Bridget Jones’ Diary [2001], Sweet Home Alabama [2002], 13 Going on 30 [2004]). Even a film such as Serendipity (2001), which would initially appear to be the rule-proving exception in the genre when it abruptly separates its protagonist couple after an early meeting in which both feel they are meant for each other, ultimately offers a sham refutation of the destiny principle only to reconfirm it. In television, reality series such as Wife Swap (ABC) stage artificial and heavily contrived forays across class lines while reinforcing the notion that women inevitably operate to secure domesticity and stability. Just as each episode of a series like this closes with the restoration of women back in their proper place, many of the forms of popular culture I analyze in this book (and particularly in Chapter 2) engage the postfeminist promise of coming back to oneself in a process of coming home.

Through the study of representation this book seeks to pin down and examine a widespread set of feelings in American life. While it emphasizes the abundant fantasies of evasion, escape, and retreat that circulate in current American popular culture it tries to do so in a spirit of awareness for why such fantasies would be attractive now. As Johanna Brenner has noted, “It is not only the pressures of everyday survival but the barrenness of politics that pushes women to seek solutions in a perfected personal life.”11 In a similar vein, Imelda Whelehan has speculated that “It may be the case that some women embrace the opportunity to feel ‘needed’ as an antidote to the alienating effects of the workplace.”12 The goal of this book is not to trade one set of caricatures for another; rather, the analysis is attentive to the ways postfeminism “works on” some of the most intractable problems in American life, noting that women’s choices and behaviors are often presented as crucial to the resoluti...