![]()

Chapter 1

The Young Achievers Science and Mathematics Pilot School

Step in the door at Young Achievers and you can feel the vibe. In the teachers’ room you’re greeted heartily with broad smiles. The building, though old and well worn, is pristinely tidy, conveying the sense that it is well cared for by staff and students. The main hallway is lined with framed posters proclaiming: National Hispanic Heritage Month, National Black History Month: We Are All Equally Different, National Asian American Heritage Month, and National Native American Heritage Month. The assistant principal strolls the halls and projects authority. He’s dressed in a sharp green suit, silk tie, beaded necklace, well-coiffed dreads. A teacher confided to Sobel that one of her young students thought he was the president. “Of what?” Sobel asked naively. “The president of the United States, of course,” she responded. Names on the lockers read Jahzell, Mykayla, Tyriq, Alyria. Definitely not Kansas, but the power of the ruby red slippers is at work here. This is an academically together, happening place. The teachers are “a bunch of intellectual artists,” one staff member described. One external evaluator of the school concluded that:

Extremely high aspirations and deeply rooted values tangle with the reality of the logistical, personal, political constraints that are inherent in an urban school setting. The overall sense is that Young Achievers is on the edge of something really big, riding an exhilaratingly tall wave that could break at any moment.

(Duffin and PEER Associates, 2007)

The Young Achievers School is one of Boston’s original pilot schools, founded in response to the Massachusetts Education Reform Act of 1993. Now there are 20. The goal of the pilot school program is to develop pioneering models of education within the Boston Public School District and to disseminate best practices to other schools. The school was created by community activists from Roxbury and Dorchester who believed that schools were not providing adequate literacy in math and science to students of color. The school aspires to a curriculum based on active learning that is culturally relevant and free from cultural biases and that concentrates on addressing individual needs. The student population is 67 percent African American, 23 percent Latino and Hispanic, 6 percent White, 2 percent Asian, and 2 percent Native American. Owing to Boston’s school choice program, students come from many Boston neighborhoods, including Dorchester, Mattapan, Hyde Park, Roxbury, Jamaica Plain, Roslindale, and others. Over 65 percent of the students receive free or reduced-price lunch.

In 2002, the Young Achievers principal, Jinny Chalmers, and her staff expressed interest in participating in the Antioch University New England-based CO-SEED program, a school improvement/community development initiative grounded in the principles of place- and community-based education. The program, funded by regional foundations, supports school improvement through providing professional development in many forms, a professional facilitator, a community vision-to-action forum for engaging community members, grant money for the school to disburse to appropriate projects, and a half-time place-based educator from a local community organization.

Prior to this time most CO-SEED projects had been in towns and small cities in New Hampshire and Vermont, with the exception of the Beebe School in Malden, Massachusetts, the organization’s first urban site. All of the lead community partners had been environmental organizations such as the Harris Center for Conservation Education, New Hampshire Audubon, the Appalachian Mountain Club, and the Stone Zoo. These partners were referred to as Environmental Learning Centers or ELCs. Young Achievers and other Boston CO-SEED schools were invited to participate in choosing their own community collaborator. Young Achievers’ decision to partner with the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative (DSNI), a prominent social justice organization in Roxbury about two miles from the school, is an indicator of how place- and community-based education can evolve in urban settings.

Roz Everdell, education director of DSNI, was enthusiastic about the possibility of working with Young Achievers. One of the goals of the neighborhood association has been development without displacement and gentrification, something local residents have accomplished through sustained participation and engagement. As Everdell says, “Our goal is for students to understand that positive change happens because local citizens make it happen. Then perhaps they’ll understand that they’re the change agents that will keep the improvements happening.”

At the Young Achievers School, the tenets of “critical pedagogy” are married to the tenets of place- and community-based education. The purpose of critical pedagogy is what Paulo Freire calls conscientizacao, which involves “learning to perceive social, political, and economic contradictions and to take action against the oppressive elements of reality” (Gruenewald, 2003, p. 5). The Young Achievers School seeks to do this by improving science and math instruction for students of color so they can compete and succeed in the high-technology businesses in the greater Boston area. The Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative does this by making it possible for African-American, Latino, and Cape Verdean residents to shape the destiny of their own community. The Young Achievers School has provided an opportunity to discover how to nurture academic achievement through an educational focus on social justice in places traditionally underserved urban students call home. What does such an education look like?

Bringing Community Members into the School

It is not uncommon for teachers in many of the nation’s inner-city schools to have little if any connection to the neighborhoods where their students live. Their lack of direct knowledge of students’ experience makes the crafting of appropriate place- and community-based learning opportunities difficult. Class, racial, and ethnic differences can compound this challenge. In an effort to overcome these difficulties, administrators and teachers at the Young Achievers School are working to create new roles for community members to give them more responsibility for the education of their own and their neighbors’ children.

One of these roles has emerged as a result of a distinctive feature of the Young Achievers School, a Seamless Day Program that provides educational offerings from 7:30 a.m. to 4:45 p.m. each day. This came about in part to serve working parents who either had to leave children supervised by siblings at home after school or faced the challenge of getting children to childcare or after-school programs during the work day. The before- and after-school components of the day are not considered childcare, but instead are considered additional opportunities for extending the curriculum and learning. Therefore, the school day runs from 9:00 to 4:45, and the period of time from 3:15 to 4:45 provides more open-ended time for clubs, field trips, and in-depth explorations. To staff this long school day, each classroom has both a classroom teacher and a community teacher. Classroom and community teachers collaborate and overlap during the middle of the school day, with the classroom teachers arriving and leaving earlier and the community teachers arriving and leaving later.

Principal Jinny Chalmers provides a convincing rationale for why incorporating community members in this way may be important to urban place- and community-based educational efforts that aim to address social justice issues:

Environmental education has not historically taken on the issue of social justice. Here, we work at the intersection between critical pedagogy and environmental justice. All of our community teachers except one are going to the summer institute [a professional development training in place- and community-based education]. The community teacher role is a sustainability piece because it links us to the actual communities where students come from. They’re really core because you can’t just have only the professional class understanding the issues. It’s also core to our inclusion model.

(Duffin, 2005)

Originally, the community teacher was identified as a teacher aide. But, as place-based education and connecting the curriculum to the community became a more salient feature of the school, it made sense to change the title of this position. Additionally, the titles of classroom teacher and teacher aide implied a hierarchical relationship. The administration and the staff wanted to find a way to suggest greater parity and more of a collaborative relationship—hence the switch from teacher aide to community teacher. Although vestiges of the previous distinction still exist, more and more, classroom and community teachers are perceived as coteachers. Much professional development is targeted for community teachers and seeks to support those who want to gain further credentialing.

To achieve equity, a number of strategies have emerged. A conscious attempt has been made to raise the salaries of community teachers to bring them closer to the salaries of the professional staff. Specific professional development just for community teachers is being provided, and they are also being supported in their desire to pursue formal teacher certification. Community teachers are being encouraged to participate in leadership roles such as being workshop leaders at the CO-SEED summer institute. One year, community teachers trained classroom teachers and community members from rural Maine in curriculum planning. Being recognized as experts by credentialed colleagues has had an impact on their sense of competence and their contributions to the improvement of their school.

Community teachers have also had the opportunity to learn from local leaders during the community vision-to-action forum, a community/school planning session to envision the future of the school. Part of the forum included a presentation by the activist founders of Young Achievers, all African-American and Latino community members. One of the founders, Julio Henriquez, made it clear that, “If you have great expectations of children, it inspires them—they feel like they can take on any challenge.” The founders’ energy provided a role model for how community teachers can themselves become leaders in the school and community. It is this kind of inspiration, responsibility, and leadership that adults at Young Achievers seek to cultivate among their students, as well.

Finding Nature in the City

In an article entitled “Learning to Read Nature’s Book: An Interdisciplinary Curriculum for Young Children in an Urban Setting” (2006), Young Achievers kindergarten teacher Alicia Carroll and art teacher Bisse Bowman describe the rationale for a year-long curriculum that uses field trips to Forest Hills Cemetery:

Founded on our belief that outstanding curricula and competence in math and science, supported by a strong literacy program, are vital for our urban, culturally and ethnically diverse student population, our school is committed to social justice. These experiences are crucial in laying the foundations for learning scientific methods through firsthand experiences, an introduction to inquiry-based research, data gathering, recording, interpreting, and drawing conclusions. … Children in urban settings often do not have access to firsthand experiences with regional flora and fauna in natural settings, and therefore find it difficult to feel truly connected to nature, to be able to analyze and understand the natural and scientific world in which they live, and to understand their place in it. Our visits to the field study site provide our students access to all of this.

(Carroll & Bowman, 2006, p. 19)

They bundle up the children, cross Hill Street, stroll up a side street, and slip through a hole in the fence to a 10-foot square study site on the wild fringes of the cemetery. They remove the turf, set it aside, and then look for creatures.

Golden leaves rustle gently as the breeze moves through the trees in our urban forest. The children are squatting in the deep green star moss, poking their trowels underneath the moss with great care. Suddenly, a voice is raised in excitement. “Look, Ms. Alicia! Look what I found! What is it?” The excitement was catching, and the rest of the children gathered around Amir, looking into his cupped hand.

(Carroll & Bowman, 2006, p. 19)

Such investigations are the crucial first step in a comprehensive literacy and science program for these young children. From the investigations, new vocabulary lists are developed: puddingstone, moss, acorn, rustle, daddy longlegs, path. These words are incorporated into books that children write. When the children have questions about the centipedes, worms, or pupated beetles that they’re finding, these creatures are placed in a collector terrarium and brought back to the classroom. Then the teachers introduce the idea of “research,” looking in books to figure out what they’ve found. The Research Center is supplied with nonfiction insect books, Science Rookie Readers, magnifying glasses, paper, pencils, and modeling clay. During one study session, Rosa suddenly called out, “I found it. I found it! What does it say in the book? What does it say? I found it!” And sure enough, she has found an image of the mealworm pupa that Amir had discovered in the cemetery. Her enthusiasm for extracting meaning from text, illustrated in her query “What does it say in the book?,” is a perfect illustration of the power of the natural world to provoke academic learning.

For a time, the Research Center becomes “The Mealworm Research Center.” Each child set up a mealworm habitat in a petri dish and fed them not too much (which would result in rot and mold), but not too little (which would impede the development of the larvae). Students named their mealworms, watched them change, learned more new vocabulary—larva, pupa, exoskeleton, beetle, emerge—and created careful observational drawings and life cycle charts.

Carroll and Bowman place their curriculum within a broad context, touching on the possibilities of conscientizacao:

Paulo Freire, the Brazilian educator, said that authentic knowledge transforms reality. Knowledge of the word is not the privilege of the few but the right of everyone. We want to broaden our students’ scope of the world. Our students—Black, Asian, Latino/a, and White, should have the right and freedom to know the world, beginning with themselves. … When this is so, they will be able to step into the shoes of others, begin to construct knowledge that is authentic, and thereby a new reality. This is the real standard we should meet.

(Carroll & Bowman, 2006, p. 32)

Food, Farm, and Shelter

Heidi Fessenden and Nicole Weiner, first-grade teachers, conduct a year-long study of food, farm, and shelter. Though the unit evolves from year to year, it usually starts with classroom investigations of food and its sources. What kind of food do we eat? Where do we get it from? How does it get to the store? Visits to an apple orchard, a farmers’ market, and a local farm then connect students to the real world of food production. Students choose topic groups and do focused studies of bees, apple production, compost, greenhouses. They write, draw diagrams, make models, read nonfiction literature. All of this is straightforward place- and community-based curriculum grounded in real-world experiences. But, each year, there’s a twist.

Part of visiting the apple orchard involves talking to migrant workers, usually Jamaican men. The teachers use this encounter to delve deeper into the lives of these people who help bring food to children’s tables. Teachers’ guiding questions in the design of the unit are: Who are migrant farmworkers? What is hard about their lives? What rights are they fighting for? After conversations with the farmworkers and reading of related literature, students generate their own questions:

• Do they ever get fired?

• Do they have their own houses?

• How do they travel around?

• Where do they come from? Where were they born?

• Where do they bring the produce after they pick it?

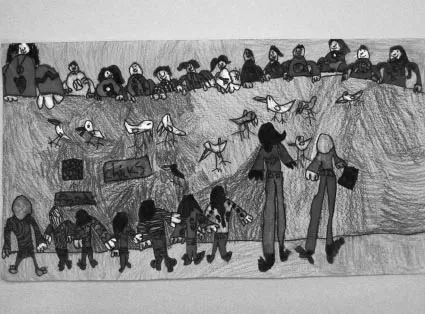

Figure 1.1 Student work from the first-grade food, farm and shelter unit

These questions guide classroom presentations, conversations with classroom visitors, and the children’s reading. One year, a visit to a migrant worker exhibit at the National Heritage Museum in Lexington led to a study of Cesar Chavez and the farmworkers’ movement. This then grew into a comparison of the non-violent protest strategies adopted by Mr. Chavez and Dr. Martin Luther King, as well as a visit from a local community activist. To culminate the study, children developed displays for local stores about what they had learned. One class presented information about migrant farmworkers at the Harvest Co-op in Jamaica Plain. The other class focused on portraits of activists and shared their work at Jamaicaway Books and Gifts.

In the fall of 2006, the u...