- 24 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The third edition of the best selling collection, Chicano School Failure and Success presents a complete and comprehensive review of the multiple and complex issues affecting Chicano students today. Richly informative and accessibly written, this edition includes completely revised and updated chapters that incorporate recent scholarship and research on the current realities of the Chicano school experience. It features four entirely new chapters on important topics such as la Chicana, two way dual language education, higher education, and gifted Chicano students. Contributors to this edition include experts in fields ranging from higher education, bilingual education, special education, gifted education, educational psychology, and anthropology. In order to capture the broad nature of Chicano school failure and success, contributors provide an in-depth look at topics as diverse as Chicano student dropout rates, the relationship between Chicano families and schools, and the impact of standards-based school reform and deficit thinking on Chicano student achievement. Committed to understanding the plight and improvement of schooling for Chicanos, this timely new edition addresses all the latest issues in Chicano education and will be a valued resource for students, educators, researchers, policy makers, and community activists alike.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Chicano School Failure and Success by Richard R. Valencia in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Current Realities of the Chicano Schooling Experience

1 The Plight of Chicano Students

An Overview of Schooling Conditions and Outcomes

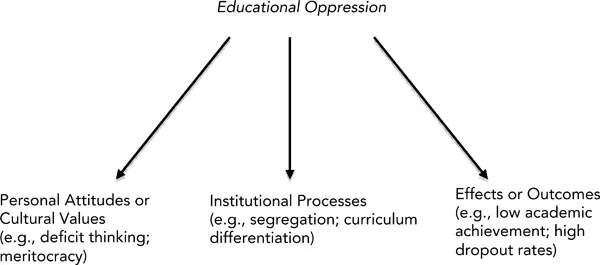

School failure among Chicanos is not a new situation. On the contrary, it is an old and stubborn condition. It refuses to relent. It continues even in the face of opposition. Imagine having a body riddled with a throbbing pain, one that never goes away, and you can get a sense of the persistent nature of the poor academic performance of a substantial portion of the Chicano school-age population. In short, Chicano school failure is deeply rooted in history.1 The historical rooting of Chicano school failure has been clearly documented (e.g., Donato, 1997, 2007; González, 1990; Moreno, 1999; San Miguel, Jr., 2003; San Miguel, Jr., & Valencia, 1998; Valencia, 2002a; Valencia, 2008). In addition to historical expressions, it also manifests in various ways in the contemporary period. In my view, such school failure has largely been shaped by educational inequality, a form of oppression. Chesler (1976), in an essay on theories of racism—which, I assert, can be generalized to the study of other forms of oppression—comments that there are three forms of evidence from which theorists can draw to identify the existence of oppression. These evidential bases—as noted in Figure 1.1—are: (a) personal attitudes or cultural values—as seen in symbol systems and ideology; (b) institutional processes—as seen in mechanisms that lead to differential advantages and privileges; (c) effects or outcomes—as seen in unequal attainments among groups. Within this framework, Chicano students—the target group of this book—are prime examples of pupils affected by the pernicious ideologies, institutional practices, and outcomes of educational inequality.

Figure 1.1 Model of Educational Oppression: Personal Values or Cultural Values, Institutional Processes, and Effects or Outcomes.

I need to underscore, however, that “how” Chicano students can achieve “school success” is also a very important topic of this book.

Chicano School Failure

Although the term “school failure” with respect to students of color (especially Chicano/Latino; African American) has been used by other scholars (e.g., Boykin, 1983; Collins, 2003; Dowrick & Crespo, 2008; Erickson, 1987; García, 2001; Ginsburg, 1986; McDermott, 1997; Siegel & Welsh, 2008), the notion itself is in need of further theoretical development and refinement. Its heuristic value and potential in theory generation about the many schooling problems experienced by Chicano students appear to be vast. How might one conceptualize school failure, a construct, among Chicano students? I offer this broad, working definition: School failure among Chicano students refers to their persistently, pervasively, and disproportionately low academic achievement. Next, I turn to a brief discussion of each of the italicized terms.

Persistence

When Chicanos did eventually gain wider access to public schooling at the turn of the twentieth century (Cameron, 1976; San Miguel, Jr., 2003; San Miguel, Jr., & Valencia, 1998), major problematic conditions (e.g., segregation) and outcomes (e.g., poor academic achievement) emerged and strenuously persisted for decades. Numerous studies reporting achievement test data and other indices of achievement since the 1920s (e.g., Drake, 1927; Manuel, 1930) and through the 1930s (e.g., McLennan, 1936; Reynolds, 1933), 1940s (e.g., Cromack, 1949; McLean, 1950), 1950s (e.g., Clark, 1956), 1960s (e.g., Barrett, 1966), 1970s (e.g., Carter, 1970; Carter & Segura, 1979; U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, 1971a, 1971b), 1980s (e.g., Brown & Haycock, 1985), 1990s (Campbell, Voelkl, & Donahue, 1997; Texas Education Agency, 1998), the 2000s (Campbell, Hombo, & Mazzeo, 2000; Texas Education Agency, 2000, 2008; Valencia, 2002b), and the present all confirm that many Chicano students have not achieved as well in school compared to their White peers (either by using direct Chicano/White comparisons or White normative data comparisons).

Pervasiveness

Chicano school failure is not confined to one single location. Wherever Chicano communities exist—from Los Angeles, California to Durham, North Carolina—school failure appears to be widespread among Chicano student enrollments—especially in schools with high percentages of students of low-socioeconomic status (SES) background. There are at least two evidential ways of looking at the pervasive character of such low academic achievement. First, one can analyze it from a geographical vantage point. Whether one views the academic performance data described in national reports (e.g., Coleman et al., 1966; National Center for Education Statistics, 2009), regional reports (e.g., U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, 1971b), state reports (e.g., Brown & Haycock, 1985; Texas Education Agency, 2008), or numerous local reports (e.g., Austin Independent School District, 2009; San Diego County Office of Education, 2009), the results are alarmingly consistent: Chicano students, on the whole, tend to exhibit low academic achievement compared to their White peers. Second, one can study such data using a cross-sectional approach—that is, comparing various grade levels at one point in time (e.g., see Brown & Haycock, 1985; Texas Education Agency, 2008). Again, Chicano academic performance—on the average—is characterized by poor achievement. In sum, the pandemic branches of Chicano school failure are clearly tied to their persistent taproots.

Disproportionality

The modifying term, “disproportionately,” is an important qualifier in that Chicano school failure, which contains its explicit meaning of low achievement, also has a connotation—comparative performance. In the context of examining the school achievement of Chicano students, their academic performance is frequently compared to White students. Here, the common procedure is to use the aggregated performance (e.g., reading achievement as measured on a standardized test) of White grade-level peers as a comparison and then to contrast the aggregated performance of Chicano students to this reference group. When this is done, the common result is one of asymmetry. That is, when the Chicano distribution of achievement test scores, represented as interval data, is superimposed over the curve of the White grouped scores, the Chicano distribution is often positively skewed. Simply put, there is a disproportionately greater percentage of Chicano students, compared to their White peers, reading below the middle of the White distribution. Conversely, compared to White students, there is a disproportionately lower percentage of Chicano students reading above the middle of the White distribution.

In addition to examining the notion of disproportionality of achievement scores from a perspective of asymmetry, once can also look at disparity. For example, when a comparison is made between the percentage of Chicano secondary school dropouts to White dropouts (i.e., represented as dichotomous data—dropout/non-dropout), the common pattern shows disparity, where the Chicano rate of dropouts in secondary schools is higher than one would predict when compared to the percentage of Chicano students in the general secondary school population.

Before we leave the term disproportionality, a caveat is in order. Although the difference between Chicano and White students in academic achievement is large, there is considerable variability in Chicano academic development and performance (see Laosa & Henderson [1991] for a discussion of some predictors that help to explain such variability; see Valencia & Suzuki [2001] for a discussion of correlates of the intellectual performance of Chicanos and other students of color). Some Chicano students do read at or above grade level and graduate from high school (e.g., Meier, Wrinkle, & Theobald, 2002; Muñoz & Hawes, 2005; Skrla, Scheurich, Johnson, & Koschoreck, 2004). In short, there are noticeable within-group differences, and thus the issue of disproportionality is not confined only to between-group (i.e., White/Chicano) differences. We must not forget that within-group differences in academic achievement typically exceed between-group differences. That is, the vast proportion of the variability in academic achievement (and intellectual ability) lies within racial/ethnic and socioeconomic groups, not between them (Valencia & Suzuki, 2001). Notwithstanding the reality that some Chicano students do not have academic problems, it is important to underscore, however, that given the current schooling outcomes experienced by many Chicano students as measured by most achievement indicators, the available evidence indicates that low academic achievement is the norm for a substantial portion of the Chicano school population in the nation’s public elementary and secondary schools (Campbell et al., 2000; National Center for Education Statistics, 2009).

Low Academic Achievement

I have deliberately chosen the term “low academic achievement” rather than the often-used notion of “underachievement.”2 It is tempting to want to use the construct of underachievement as it connotes that the typical group performance of low test scores and high dropout rates among Chicano students are not truly reflective of what they are capable of achieving. Although there is likely a great deal of credence to the belief that the depressed academic achievement of Chicanos does not reflect what they can do, an attempt to interpret this discrepancy as “underachievement” presents two conceptual problems.

First, the converse notion of underachievement (i.e., “overachievement”) appears to be “a logical impossibility” (Anastasi, 1984, p. 131) because the term implies that a person is academically performing above his/her capacity (as measured by an intelligence test). Second, the terms under-achievement/overachievement are meaningless if not looked at from a measurement perspective (Anastasi, 1984; Jensen, 1980). Anastasi (citing Thorndike, 1963) has noted: “Actually, the question of underachievement and overachievement can be more properly formulated as overprediction and underprediction from the first to the second test” (p. 131). These intraindividual differences from one measure to another merely inform us “that no two tests are perfectly correlated” (see Anastasi, 1984, p. 131). The problems attached to the term underachievement (as well as overachievement) are so grave that they have led Lee Cronbach, a highly noted tests and measurement expert, to conclude: “The terminology of over- and underachievement should be abandoned” (1984, p. 255). Given all the confusion and issues associated with the term underachievement, I have selected the term “low academic achievement”—a more meaningful construct—for inclusion in my definition of Chicano school failure.

Theoretical Perspectives Proffered to Explain School Failure

What accounts for school failure experienced by a sizeable proportion of low-SES Chicano students and other students of color?3 Scholars have offered many contrasting explanations, and we should best think of them as “families” of explanatory paradigms. In brief, these models focus on the following points:

Communication Process

The earliest variant of this family of models is the “cultural difference” framework, which has its roots in the early 1970s (Baratz & Baratz, 1970; Labov, 1970; Valentine, 1971). This perspective, launched as a reactive, but serious critique of the 1960s deficit thinking models (see Pearl, 1997a), asserts that one should view the putative deficits among children and families of color (particularly of low-SES background) more accurately as differences. Proponents of the cultural difference framework contend that the basis of the discontinuity between student and school often lay in a mismatch between the home culture and the school culture (e.g., regarding children’s mother tongue; children’s learning styles) that leads to learning problems for culturally diverse students (e.g., Hale-Benson, 1986; Ramírez & Castañeda, 1974). Regarding the early research on culturally shaped learning styles, scholars have critiqued this viewpoint for its unsupported generalizations, and even stereotypes (see Irvine & York, 1995).

As scholarly discourse of the cultural difference model evolved, one variant focused on possible misunderstandings between student and teacher in verbal and nonverbal communication styles (Erickson, 1987). Such misunderstandings from these marked boundaries, scholars assert, often result in teachers labeling students as unmotivated to learn. In short, such linguistic differences may lead to trouble, conflict, and school failure. An insightful analysis of this communication process perspective is seen in Lisa Delpit’s 1995 book, Other People’s Children: Cultural Conflict in the Classroom.

Caste

Another explanation of school failure lay in “caste theory,” a model advanced by the late educational anthropologist John Ogbu (see, e.g., Ogbu, 1978, 1986, 1987, 1991, 1994). In his numerous writings, Ogbu classifies racial/ethnic minority groups in the United States as either “immigrant minorities” (e.g., some Latinos from Central America; Koreans; Japanese) or nonimmigrant or “involuntary minorities” whose current societal status is rooted in slavery (e.g., African Americans), conquest (e.g., American Indians), or conquest and colonization (e.g., Mexican Americans; Puerto Ricans). Sometimes referr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Part I: Current Realities of the Chicano Schooling Experience

- Part II: Language Perspectives on Chicano Student Academic Achievement

- Part III: Cultural and Familial Perspectives on Chicano Student Academic Achievement

- Part IV: Educational Assessment and Placement Issues Regarding Chicano Students

- Part V: The Big Picture and Chicano School Failure and Success

- Contributors

- Index