![]()

1 ‘Nature’, ‘environment’ and social theory

Key issues

• What is social theory?

• Environment, nature and the nonhuman.

• Social theorising and the environment.

• The uses and abuses of the environment in social theory.

• Four environments for humans in social theory.

• The ‘reading-off’ hypothesis.

Introduction

What does one consider when one thinks about the ‘environment’? Is the environment the trees, plants, animals that we see around us? Is it the Amazonian rainforests or the world's climate systems upon which all life on the planet depends? Are genetically modified organisms part of the environment? Is the environment the same as ‘nature’? Does the ‘environment’ have to do with concepts such as ‘biodiversity’, ‘ecosystems’ and ‘ecological harmony’? Can we say that the room where you are probably reading this book constitutes an ‘environment’?

The problem (which can also be an advantage) with the concept ‘environment’, like many other concepts such as ‘democracy’, ‘justice’ or ‘equality’, is that it can take a number of different meanings, refer to a variety of things, entities and processes, and thus cover a range of issues and be used to justify particular positions and arguments. While of course the environment cannot refer to anything (that is, it refers to some identifiable and determinant set of ‘things’), it is an extremely elastic term in that there are many things – the room you are sitting in, the book itself, the chair, the desk, other people, the fly on the window, and the unseen micro-organisms and the air around you – all of which could be considered to constitute your present and immediate ‘environment’. Like many things, the environment can mean different things depending on how you define and understand it, or who defines it.

In many respects thinking about and theorising the environment is one of the most enduring aspects of human thought. For example, the question of the proper place of human society within the natural order has occupied a central place in philosophy since its beginnings. Hence, why, how and in what ways the environment, and related concepts such as ‘nature’ and the ‘natural’, are used in social theory is not only extremely interesting but absolutely crucial, given the different meanings and power of these terms when used in argument and justification. For example, calling something ‘natural’ implies that it is beyond change, immutable, fixed and given. Hence the power of using this term to justify a particular argument, and the need to be aware of how and why the environment and related concepts are employed in social theorising.

At the same time, alongside the theoretical or academic interest, there is a very important practical aspect to thinking about and theorising the environment in relation to society. This has to do with the increasing quantity and quality of environmental problems which face every society on Earth, both nationally and globally. Global warming and climate change, deforestation, desertification, pollution, biodiversity loss and the controversies over the benefits and dangers of genetic engineering and biotechnology – all are familiar terms in our everyday lives. All of these, and others, seem to suggest that there is an ‘environmental crisis’ which faces humanity (and the nonhuman world), the like of which is unprecedented in human history. For the first time in history, humanity has at its disposal the capacity radically to alter the environment (primarily through the application of science and technology), and even has the capacity (though thankfully still not the willingness) to completely destroy life on Earth ‘as we know it’ (as Dr Spock would say) through the collected nuclear, biological and chemical weapons of mass destruction possessed by a minority of the world's nations. At the same time as being the first generation which has this capacity to affect the environment, one could also say that (particularly since the rise of the green or environmental movement) this is the first generation which knows (or at least has some sense) that it is transforming the environment in a way which will affect the state of the environment inherited by future generations. Hence thinking about or analysing the role or place of the environment in social theory (the aim of this book) is not simply of theoretical, but also of great practical interest.

The importance of analysing the environment and social theory can also be seen when one considers that the majority of the world's environmental problems are largely the result of human social action or behaviour. Global warming, for example, is accepted by the vast majority of the world's scientists to be the result of increased carbon emissions by humans, principally through energy production and consumption (the burning of fossil fuels, such as coal, gas and petroleum to create electricity) and forms of transport which rely on such fossil fuels. Hence social theory, defined below as the systematic study of how society is and ought to be, has an important role to play in explaining, understanding and providing possible solutions to the ‘environmental crisis’.

What is social theory?

‘Social theory’ as a field of study is particularly difficult to accurately determine or define. As understood here, social theory is the systematic study of human society, including the processes of social change and transformation, involving the formulation of theoretical (and empirical) hypotheses, explanations, justifications and prescriptions. In disciplinary terms ‘social theory’ is often associated with sociological theory, and modern social theory has its origins in the sociological tradition. This book however, takes a broad rather than a narrow understanding of social theory, in that it encompasses sociological theory but goes beyond it to include other disciplines and intellectual traditions and approaches. As may be seen from the range of authors and disciplinary approaches surveyed in this book, social theory includes the ‘social-scientific’ approach to the study of society (in terms of the disciplines one finds in the social-scientific approach to studying society and social phenomenon – sociology and anthropology, politics, international relations, economics, legal studies, women's studies, cultural studies). However, social theory may also include the disciplinary approaches of history, philosophy and moral theory and cultural geography. Thus ‘social theory’ acts as an umbrella under which are gathered a range of approaches to thinking about society, explaining social phenomena, and offering justifications for advocating or resisting social transformation.

The main disciplinary approaches of this book are: sociological theory (including cultural theory), political theory, economics and political economy, but it also includes the history of social thought. In broad terms what may be called an interdisciplinary conception of social theory is used throughout the book.

The historical origins of social theory may be found in the Enlightenment, though aspects of modern social theory may also be found in pre-Enlightenment thinkers and schools of thought (particularly in political philosophy and political economy, as outlined in Chapters 2 and 3). And it is in reaction to the Enlightenment, and the emergence of ‘modern society’, that a large part of past and contemporary social theory finds its subject. It is in the spirit of the early emergence of social theory that a broad understanding of it is adopted here. In its origins, social theory covered the broad field of the systematic or disciplined study of society in all its various aspects: political, economic, cultural, social, legal, philosophical, moral, religious and scientific. Social theory as the systematic or scientific study of society included looking at such social phenomena as the relationship between the individual and society, the origins and character of cultural practices, and the relationships within and between everyday life and social institutions, such as the family, the nation, the state and the economy. As May points out, in the nineteenth century the main trends in social theory were ‘First, an interest in the nature or social development and social origins. Second the merging of history and philosophy into a “science of society”. Third, the attempt to discover rational-empirical causes for social phenomena in place of metaphysical ones’ (May, 1996: 13). In a similar fashion, this book attempts to offer an equally broad and inclusive view of social theory, though of course many issues, writers and ideas are necessarily left out, or only briefly mentioned. At the same time, we can use the Enlightenment as a way to demarcate modern social theory by noting that the ‘subject’ of modern social theory is ‘the analysis of modernity and its impact on the world’ (Giddens et al., 1994: 1). In particular, modern social theory analyses the impact of the industrial, liberal-capitalist socioeconomic system which has come to shape the modern global and globalising world.

Social theory typically has two dimensions, one descriptive the other prescriptive. In its descriptive aspect, social theory describes society and advances particular explanations for social phenomena, events, problems and changes within society. For example, a social theory may involve explaining the emergence of contemporary far-right politics across Europe by reference to a rise in unemployment, the negative economic effects of globalisation and a consequent appeal of populist nationalist politics in response to the erosion of ‘national sovereignty’ or ‘national pride’.

The prescriptive dimensions of social theory are the ways in which social theory not only tells a story of the way society is, but also tells how society ought to be. Here social theory advances particular normative or value-based arguments, justifications and principles to support its claims about how society ought to be ordered, changed or whatever. This prescriptive aspect of social theory can broadly take two forms. On the one hand, it can seek to justify the present social order, that is, suggest that the way society is is how it ought to be. This may be described as a ‘mainstream’ or ‘conservative’ position in which the aim of social theory is to legitimate, defend and justify the current way society is organised, its principles, institutions and ways of life.

On the other hand, some forms of social theory seek to argue that society ought to be transformed, organised along different principles and with different institutions from those upon which the current social order is based. These forms of social theory may be broadly described as ‘critical’ in that they are critical of the current way society is organised and seek to provide reasons for why it ought to be changed and organised along different principles or with different institutions. The classical example of a critical form of social theory is Marxism, which criticises the current capitalist, liberal democratic organisation of societies in the ‘West’ or ‘developed’ world, suggesting an alternative ‘communist’ or ‘socialist’ mode of social organisation. Below are some examples of mainstream and critical forms of social theory which will be looked at in this book.

| Mainstream social theory | Critical social theory |

| Conservatism | Marxism/socialism |

| Neo-classical economics | Feminism |

| Sociobiology | Ecologism/green social theory |

| Social Darwinism | Postmodernism |

While it is nearly always an advantage to adopt broad and flexible, rather than narrow and rigid, approaches to the study of society, such an approach is particularly advantageous (indeed, some would say necessary and not just desirable) when it comes to social theory and the environment. The adoption of an explicitly interdisciplinary approach to studying the relation between society and environment is something that has become a dominant perspective in recent work in this area (Barry, 1999b), and will be discussed in greater detail in Chapter 10. In part, this is due to the rather simple fact that there is not just one relation between society and environment (as this and other books in the Routledge Environment and Society series seek to demonstrate). Rather, the relation between society and environment denotes a series of relationships: physical, social, economic, political, moral, cultural, epistemological and philosophical, covering a multifaceted, multi-layered, complex and dynamic interaction between society and environment. Given the multiple relations between society and environment, it is clear that no one discipline or approach can hope to capture the full complexity of the various relations between society and environment. Hence an interdisciplinary approach drawing on a variety of sources is not only useful, but in some ways is necessary in discussing how the environment has been conceptualised, used and abused within social theory.

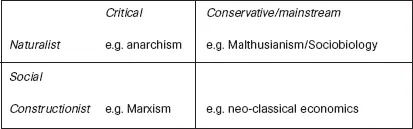

With regard to social theorising about nature or the environment (and as indicated below, the two are not necessarily the same), one can trace two other approaches alongside critical and mainstream. These are what one may call ‘naturalist’ and ‘social constructionist’ approaches. Naturalist social theorising about the environment generally takes the view that the environment is external to society and exists as an independent ‘natural order’ outside of society. Social-constructionist approaches, on the other hand, see ‘environment’ and ‘nature’ as constructions of society, and therefore focus on analysing the internal relations within society. Combining them together, we get a fourfold schema of social theoretical approaches to the environment. This schema may be used as a rough guide to understanding particular social theories and theorists.

Figure 1.1 Social theory and the environment schema

Source: Author

Environment, nature and the nonhuman

One way of starting our exploration of the place or role of environment in social theory is to look at what we mean by ‘environment’. First, we can note that the environment is an ‘essentially contested’ term. The phrase ‘essentially contested’ simply means that the term has no universally agreed and singular meaning or definition. The importance of these issues should of course be obvious when social theorising about the environment and its relationship to human social concerns. One of the first and most obvious issues about the environment and social theory concerns the fact/value distinction. This refers to the way in which the environment, and related terms, are used not just in a descriptive sense, that is dealing with the facts, but how they are also used to express, justify or establish particular values or judgements, courses of action and reaction, policy prescriptions and ways of thinking. Thus while the environment is used to simply describe the world, that is, to tell us how the world is, it is also used to prescribe how the world ought to be, or making some normative (value) claim about something. For example, the term ‘natural’ carries with it a host of different value meanings, sometimes positive ones of ‘wholesome’ or ‘healthy’ (as in organic food), sometimes negative ones, ‘uncultured’ or ‘backward’ (as in passing judgement on a group's way of life).

A good way to start thinking about the environment is to list its various definitions and understandings. Often when one is trying to define terms or concepts, a good place to start is a dictionary and thesaurus. Here are some definitions of ‘environment’ that can be found:

environment: ‘surroundings, milieu, atmosphere, condition, climate, circumstances, setting, ambience, scene, decor’ (taken from a computer thesaurus).

environment: ‘situation, position, locality, attitude, place, site, bearings, neighbourhood’ (Roget's Thesaurus, 1988).

environment: ‘surroundings, conditions of life or growth’ (Collins English Dictionary and Thesaurus, 1992).

Thus while the environment is often taken to mean the nonhuman world, and sometimes used as equivalent to ‘nature’, it can take on a variety of meanings. The roots of the term ‘environment’ lie in the French word environ which means ‘to surround’, ‘to envelop’, ‘to enclose’. Another closely related French word is ‘milieu’, which is often taken to mean the same as environment. An important implication of this idea of environment is that ‘An environment as milieu is not something a creature is merely in, but something it has’ (Cooper, 1992: 169). What Cooper means by this is that environment is not just a passive background or context within which something lives or exists. It is also something that is possessed in the sense that to have an environment is an important part of what the creature or entity is. That is, to have an environment is a constitutive part of who or what the creature is, so that one cannot identify a creature without referring to its environment. On this reading, anything that surrounds or environs is...