1

INTRODUCTION

Our Earth is ever changing. Continental plates shift, ocean levels rise and fall, mountains and shores erode, deserts and glaciers move, and natural disasters change the face of the globe. These are natural processes that have been shaping the surface of the Earth for billions of years. Over a much shorter period of time, formerly insignificant organisms known as homo sapiens began to shape natural environments to fit their needs. This is not unusual for organisms: Certainly, all plants and animals will transform natural surroundings to fit their needs. However, humans were different in that they not only sought actively to control their surroundings, but they managed to colonize every habitable surface ecosystem on the planet, from high mountains to low valleys, and from Arctic tundra to equatorial deserts. As the population of humans grew and their social structures became more complex, the effect of these creatures on the surface of the Earth became more noticeable. Indeed, as both social and cognizant creatures with a penchant for controlling the world around them, human beings developed a unique relationship with their surroundings. Understanding this special relationship between humans and their environment, which archaeologists, geographers, and other scholars often call “social landscapes,” is one of the most pressing issues facing us in the 21st century.

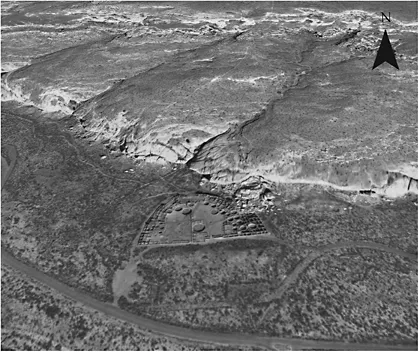

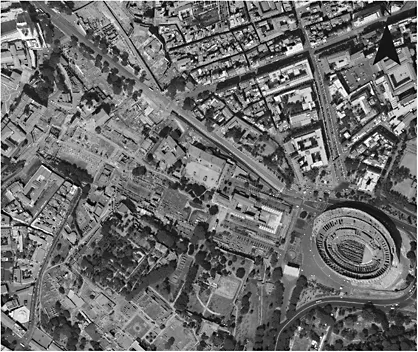

How scholars and scientists detect these social landscapes has evolved with advances in technology, and stands to have an enormous impact on the fields of archaeology, history, geography, environmental sciences, and other related fields. How past places on Earth can be made visible (Gould 1987) is a topic that has received significant attention in the media and in classrooms. Although most archaeology relies on visual recognition of past remains, seen in Figure 1.1 (e.g. “the deposit of statues was found in a foundation trench,” or “level 3B in square IV contains mainly broken faience amulets from the Middle Kingdom”), the majority of archaeological remains and features are hidden from view, whether buried underground by environmental processes (e.g. ancient river courses, old lakes, field boundaries), covered over by modern towns (e.g. Rome, seen in Figure 1.2, or in Greece), or by modern vegetation (e.g. forests covering settlements in Europe). The use of satellite remote sensing can not only reveal these hidden, or so-called “invisible,” remains, but can place them in much larger contexts, showing past social landscapes in all their complexity.

What is satellite remote sensing, and how can it be applied to archaeological research? Satellite remote sensing is the specific application of satellite imagery (or images from space) to archaeological survey (Zubrow 2007), which entails searching for ancient sites on a particular landscape at different scales (Wilkinson 2003). While aerial photography (Deuel 1973; Kenyon 1991; Wilson 2000), geophysics (Schmidt 2001; Witten 2005), laser scanning of monuments including Stonehenge, see Goskara et al. 2003), virtual reality (Broucke 1999; Barcelo et al. 2000), imagery analysis within geographic information systems (GIS) (Chapman 2006; Conolly and Lake 2006), and satellite imagery analysis are all forms of remote sensing—and all are invaluable for archaeological investigations—the application of satellite remote sensing in archaeology is the primary focus of this book.

Figure 1.1 Digital elevation model of Chaco Canyon, New Mexico (scale 1:122 m), 2008 image courtesy of Google Earth™ Pro.

Figure 1.2 The Forum, Rome (scale 1:244 m), 2008 image courtesy of Google Earth™ Pro.

All forms of remote sensing, including imagery analysis in a GIS, geophysics, satellite remote sensing, and aerial photography are concerned with the identification of “anthropogenic” features in such a landscape, whether they are detecting a structure, such as a building or a town, or a system of irrigation channels and roads. In fact, “remote sensing” is a term that refers to the remote viewing of our surrounding world, including all forms of photography, video and other forms of visualization. Satellite remote sensing has the added advantage of being able to see an entire landscape at different resolutions and scales on varying satellites imagery datasets, as well being able to record data beyond the visible part of electromagnetic spectrum. Remote sensors can analyze imagery so that distracting natural invisible or anthropogenic features on that landscape (such as forests or buildings) can be made, while ancient remains previously invisible to the naked eye appear with great clarity. In this way, satellite remote sensing can reconstruct how past landscapes may have looked, and thereby allows a better understanding of past human occupation of those landscapes.

How can people apply satellite remote sensing from space to archaeological investigations? As human beings, we can only see in the visible part of the electromagnetic spectrum. The electromagnetic spectrum extends far beyond the visible parts of the spectrum to the infrared, thermal, and microwave, all of which have been used by archaeologists to see through or beneath rainforests, deserts, and modern debris to locate past remains. Recent archaeological findings using the electromagnetic spectrum include the discovery of many ancient Mayan sites in Guatemala (Saturno et al. 2007), ancient water management strategies at Angkor Wat (Evans et al. 2007), and details of how Easter Island statues were transported (Hunt and Lipo 2005), to name a few. Satellites record reflected radiation from the surface of the Earth in different parts of the electromagnetic spectrum, with every satellite image type recording this information slightly differently. A more detailed discussion of the electromagnetic spectrum appears in Chapter 3. Ancient archaeological remains will affect their surrounding landscapes in different ways, whether through altering the surrounding soils, affecting vegetation, or absorbing moisture at a greater or lesser rate. On the ground, we cannot see these subtle landscape changes visually. Archaeologists are not necessarily “seeing” beneath the surface with multispectral satellite imagery when using remote sensing techniques; they are actually seeing the discrepancy between higher and lower moisture and heat contents of buried walls, which affect the overlying soils, sands, and vegetation. How individuals choose to manipulate satellite data to obtain these results will vary greatly depending on landscape type, satellite image type, and the overall research goals of the archaeological project.

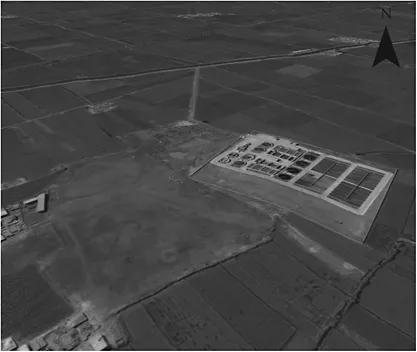

The majority of satellite survey work in archaeology, however, has focused on visible archaeological site detection; enlarging satellite images to find sites or landscape features. There is much we can miss by being on the ground by not seeing things from an aerial perspective, as shown by Figure 1.3. Visual satellite datasets are a valuable tool for overall landscape visualization and site detection, as satellites give a far broader perspective on past landscapes. However, visual data represents only a tiny proportion of what satellites can offer the archaeologist in feature detection. Not making use of the full electromagnetic spectrum leaves countless archaeological features or sites undiscovered.

Figure 1.3 Babylon, Iraq (scale 1:1000 m), note modern reconstruction in the northern part of the site, 2008 image courtesy of Google Earth™ Pro.

The development of this methodology has already contributed to the discovery of tens of thousands of new archaeological sites and features across the globe, with many of these studies discussed in detail here. If these case studies can serve as an example, there must be many hundreds of thousands (if not millions) of additional archaeological sites and features that remain currently undiscovered. This is particularly true, since in satellite remote sensing a specific methodology has not yet been developed to detect obscured ancient sites and features using the full range of satellite imagery analysis techniques. The ramifications of such new discoveries would be massive for historical and environmental research programs, and give tremendous insights into past social landscapes.

The second level of archaeological inference in satellite remote sensing is survey, or “ground truthing.” Although finding potential archaeological sites or features on a computer screen is important, and relies on detailed scientific analysis, it is impossible to know more about an archaeological site without ground confirmation. Using a global positioning system (GPS), researchers can pinpoint areas on a computer screen for surface archaeological investigation (Arnold 1993). With the ever-increasing emphasis on reducing costs, satellite remote sensing allows archaeological teams to find sites and features that they would otherwise have had to locate randomly. This has certainly happened before in archaeology: Many tombs and deposits have been found accidentally, such as the catacombs of Alexandria, Egypt, which were found when the top of the tomb shaft was breeched by donkeys walking across it (Empereur 2000). This is hardly an ideal method for locating new sites.

In some cases, surface material culture may indicate the presence of an archaeological site, while in other cases the site will be revealed by growth patterns in vegetation, chemical alterations in the soil, or close proximity to a covered natural feature. On the ground during general archaeological survey, we can certainly observe differently colored soils (Van Andel 1998) and different aspects of material culture. Surveying an entire landscape through visual observation of these features and the collection of material culture allows archaeological teams to make observations about land occupation over time. Satellite remote sensing, in combination with ground survey, coring, and excavation, allows for a holistic landscape reconstruction, by enabling the detection and assessment of invisible sites and features. Both visible and invisible archaeological features combine to give a better understanding of anthropogenic effects on past landscapes.

The third level of inference in satellite remote sensing is targeted excavations, in which archaeologists open a limited number of trenches that are strategically placed to give the maximum amount of information about that site or that landscape. In a normal excavation in which satellite remote sensing is not involved, archaeologists often will use geophysics or ground survey to determine the best placement for their trenches. In instances where geophysics is not used, perhaps the archaeological team will decide to place their trenches at higher locations (where preservation is better), or where specific surface material culture indicates certain types of subsurface structures (e.g. large amounts of slag appearing on the surface of an archaeological site may indicate an industrial area beneath the ground—Figure 1.4).

When using satellite remote sensing for excavation, however, the archaeological team can use the electromagnetic spectrum and broader visual detection to reveal features not apparent on the ground. Satellite remote sensing, in a sense, acts as an aerial geophysical sensor, identifying potential buried features such as walls, streets, or houses. Once the archaeological team knows the exact location of any potential feature, they can target their excavation trenches accordingly. Satellites may be more cost-effective than other geophysical methods, as they can be used to analyze broader stretches of land, but everything will depend on the project aims of the archaeological team. The differences described here highlight how the research agenda of a traditional archaeologist differs from that of one informed by satellite remote sensing techniques.

While there is great interest in the use of satellite remote sensing, people are generally not aware of the full potential of satellite data for archaeological work. Satellite remote sensing studies are certainly becoming more popular, evidenced by increasing numbers of related articles in journals such as the Journal of Field Archaeology, Antiquity, and Archaeological Prospection, and an increasing presence of satellite remote sensing in popular media. Many general remote sensing handbooks exist (Jensen 1996; Lillesand et al. 2004), and form required readings in introductory remote sensing courses. These books, while excellent reference tools, can be too technical for people with a more general interest in satellite remote sensing. This book does not claim to be a general remote sensing introduction or even an environmental remote sensing book (Jensen 2000): It is a book aimed at describing and evaluating the numerous applications of satellite remote sensing to global archaeological landscape evaluation, and is written to be accessible to archaeologists, students, and others interested in applying this technology to their work or learning more about the subject of satellite archaeology. Hands-on coursework is required to learn specific remote sensing programs, much like any scientific specialization in archaeology, but few courses exist at present dedicated to the teaching of satellite remote sensing in archaeology.

The choice to use remote sensing as one’s research is another topic. Does the existence of the technology alone merit developing an interest in the subject? Satellite remote sensing visualizes the confluence of human history and the environment, which archaeologists spend much of their time reconstructing. Anyone with an interest in comparing regional and national influences on a local level can benefit from having a better understanding of landscape changes and how they may have influenced site or feature placement. The very nature of archaeology is concerned with exposing hidden things, largely buried beneath the ground, to answer larger historical and anthropological questions. Satellite remote sensing in archaeology is virtually identical then to the larger scope archaeology, although the features it reveals are not necessarily buried in the same way. As in all scientific methods of analysis in archaeology, there is a right and a wrong way to conduct satellite remote sensing studies and related ground surveys.

This book will start with a detailed history of satellite remote sensing in archaeology (Chapter 2), which will emphasize the general development of satellite remote sensing versus ongoing developments in archaeology and remote sensing. Gaining an appreciation of how the field developed is important, because through understanding the history of satellite remote sensing, one can better appreciate where the field is headed.

Figure 1.4 Digital elevation model, Tell Tebilla, northeast Delta (scale 1:78 m). Note the checkerboard pattern from surface scraping during the 2003 excavation season, 2008 image courtesy of Google Earth™ Pro.

Archaeologists and other specialists have already written books on aerial photography (Deuel 1973; St. Joseph 1977; Riley 1982; Bourgeois and Marc 2003; Brophy and Cowley 2005), but it is necessary to provide an overview of basic concepts of remote sensing as they started in the early 1900s with the advent of aerial archaeology. It will also be important for archaeologists to understand the advantages and disadvantages of using satellite remote sensing in relationship to aerial photography. Used together, they present powerful past landscape visualization tools.

Chapter 3 discusses the various types of satellite imagery available to archaeologists, helping with the selection of most appropriate imagery, and provides information about ordering each image type. Access to satellite imagery is influencing how archaeologists conduct their fieldwork, while giving more individuals the ability to understand past landscapes. This access will only continue as free viewing programs, such as Google Earth™ or WorldWind, improve their resolution (Figure 1.5). Obtaining free satellite imagery is an important issue because adequate money for recent imagery may not be available. Chapter 3 also discusses the advantages and disadvantages of each satellite image type along with some of the various archaeological projects that have applied them.

Chapter 4 provides a developing archaeological remote sensing methodology, from basic remote sensing techniques to complex algorithms, which will allow cross applications of techniques across diverse regions of the globe. This chapter provides the most technical detail in the book. Satellite images are especially useful for mapmaking due to the paucity of high quality or recent maps in different regions and nations.

Figure 1.5 Digital elevation model, Hadrian’s Wall, northern England (scale 1:50 m), 2008 image courtesy of Google Earth™ Pro.

How trustworthy are such maps for archaeological analysis? As Irwin Scollar (2002) points out, maps are not images, and landscapes tend to be altered...