![]()

Appendix 1

Social Theory and Moral Philosophy

It is my overall argument that the fact-value and theory-practice distinctions, as developed and presented in contemporary ethics and orthodox philosophy of social science, are completely untenable. While facts and theories are influenced by our values and practices, it is also possible rationally to derive value and practical judgements from deep explanatory social theories. The textbook doctrine that fact and value, theory and practice belong to different realms creates an artificial barrier between sociology and ethics. It is my contention that, on the contrary, social theory just is moral philosophy, but as science.

I have three main aims in this appendix. My primary aim is to show what must be the case for an emancipatory social science to be possible. Emancipation is not to be confused with the amelioration of states of affairs. Nor does it involve the absence of determination. It consists in the transformation or replacement of unneeded, unwanted and oppressive sources of determination, or structures, by needed, wanted and empowering ones. My conception of emancipation is grounded in agents’ empirically manifest wants and identifiable needs. But to the extent that some social transformation is to be rationally emancipatory it depends not only or especially on a science of behaviour, but on a science – a depth science – of the structures generating, determining or providing the sources of behaviour. It is my intention to defend the scientificity, and elucidate the general form, of such depth-enquiries in the human sciences. This will necessitate an excursus into the philosophy of science, and more particularly social science, in the earlier part of my essay. My secondary aim is to resolve the traditional antinomies between fact and value and theory and practice; that is, to transcend the oppositions between (in a broad sense) positivism and moralism, scientism and criticism, science and critique, scientific explanation and human emancipation. My argument is that social science is non-neutral in a double sense – in that it both (a) consists in a practical intervention in social life and (b) logically entails values. It is the conative role of belief-informed and realizable wants and the explanatory power of (agents’) theories which play the crucial role in these transitions.

This paper develops the argument of PON, chapter 2; SR, chapters 2 and 3; and RR, chapter 6 and passim.

My third and final aim is to provide a critique of ‘Hume's law’. The generally accepted, and in my opinion essentially correct, interpretation of Hume is that he enunciated what has become – at least since the publication of Moore's Principia Ethica – an article of faith for the entire analytical tradition, namely that the transition from ‘is’ to ‘ought’, factual to value statements, indicatives to imperatives, is, although frequently made (and perhaps even, like eduction, psychologically necessary), logically inadmissible. In contrast, I want to argue that provided only certain minimal conditions are satisfied, it is not only acceptable, but logically mandatory.

The critical realist account of science (which I first elaborated in A Realist Theory of Science1 and has subsequently been developed by myself and others) can only be briefly summarized here. It has three main aspects. First, in ontology, it involves the transcendental refutation of the empiricist ontology informing the hitherto dominant accounts of science, and its replacement by a more complex ontology, on which the world appears as structured, differentiated and changing. From the standpoint of the philosophy of social science, the most important point to note here is that the absence of closed systems (and the impossibility of crucial experiments) means that criteria for the rational assessment of theories cannot be predictive and so must be exclusively explanatory. Secondly, in epistemology, it involves the elaboration of a rational account of scientific activity, which is conceived as engaged in the continual process of the empirically controlled retroduction of explanatory structures from the manifest phenomena which are produced by them. Thirdly, in what I have called the metacritical dimension, it consists in an examination of the metaphysical and social bases of accounts of science and the elaboration of a new conception of philosophy, on which it is conceived as incorporating aspects of Aristotelian dialectic, Lockean underlabouring, Leibnizian conceptual analysis, Kantian transcendental argumentation, Hegelian dialectical phenomenology, Marxian critique of the speculative illusion and Baconian-Bachelardian value commitment.

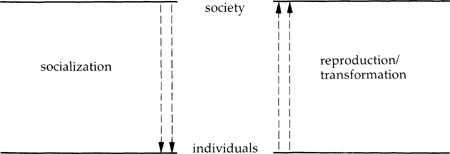

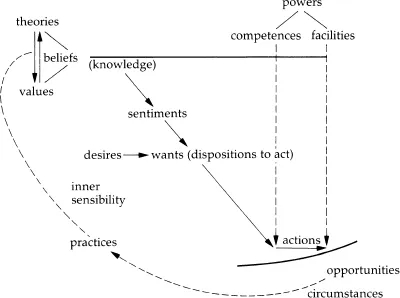

Applied to the domain of the social sciences, this perspective – of transcendental realism – enables a critical naturalism, based on an independent analysis of what must be the case for intentional action to be possible. This involves in the first place a critique of individualist and collectivist conceptions of the subject-matter of social science in favour of a relationist conception, on which its subject-matter is conceived as, paradigmatically, the enduring relationships between individuals and groups and their artefacts and nature and functions of them – relationships such as those between parents and children, employer and employees, employees and the unemployed, and so on. Secondly, it necessitates articulation of the duality of social structure and human agency or praxis,2 namely, that social structures are a necessary condition for human agency (as its means and media) but that they exist and persist only in virtue of human agency – the human agency which reproduces or transforms them. This entails what I have called the transformational model of social activity. (See figures 1 and 2.) This model has a number of consequences. First, actors’ accounts are limited by unintended consequences, unacknowledged conditions, unconscious motivation and tacit skills. Figures 2 and 4 show the feedback of consequences on the conditions of actions. It follows from the limitations on actors’ knowledge that social science has a possible cognitive role to play for human agents. And from this there follows a critique of the doctrine of interpretive fundamentalism: there is no incorrigible foundational base of social scientific knowledge in actors’ accounts. The recursive and non-teleological character of society also follows from the transformational model of social activity. As an object of enquiry, society is nothing other than the ensemble of the unmotivated conditions for our substantive motivated productions. As such it must be seen as a causally and taxonomically irreducible mode of matter – with the natural and social worlds conceived as in dynamic interrelationship. The transformational model of social activity also implies a series of ontological, relational, epistemological and critical limits on naturalism. I discussed the first three kinds of limits in The Possibility of Naturalism,3 and defend my account of them in a postscript to the second edition. It is the fourth kind of limit that I am concerned with here, as I come to the main point of my essay: a critique of the doctrine of the value-neutrality of social science.

Figure 1 The transformational model of social activity

Figure 2 Structure and praxis

Note: 1,1’ = unintended consequences; 2 = unacknowledged conditions;

3 = unconscious motivations; 4 = tacit skills.

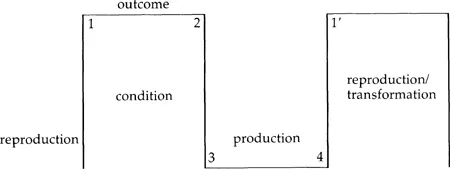

Figure 3 Fact/value helix

Note: V, T, (F) stand for values, theories and sets of facts respectively.

Table 1

| (1) V F | scientism |

| (1) V F | positivism (and displacements) |

| (3) T P | irritationalism |

| (4) T P | theoreticism (idealism) (→ P T) |

Note: F stands for facts and theories.

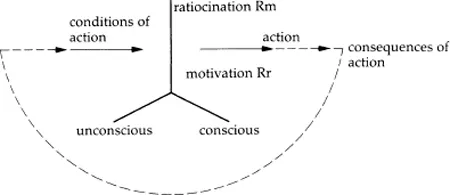

Figure 4 The stratification of action

Figure 5 The five bases of action and practices, values and theories

My contention is that while theoretical and factual considerations both causally presage and logically entail practical and evaluative ones, practical and evaluative considerations causally predispose but do not entail theoretical and factual ones. So that although there is mutual interdependence, there is not mutual entailment, which makes the fact/value helix displayed in Figure 3 (and its undisplayed theory/practice analogue) a rational one. I accept the practical and value-dependent character of social enquiry, but my main concern is to show how explanatory theories entail values and practices. And my core argument turns on the fact that the subject-matter of the social sciences includes both social objects and beliefs about those objects; and that any disjuncture or mismatch between them may enter into social explanation; so that if we can explain the (perhaps contingent) necessity for false (illusory) consciousness, then we may pass immediately to a negative evaluation of the source(s) of false consciousness; and to a positive evaluation on action rationally directed at removing it, in the way indicated in Inference Scheme 1.

I now turn more generally to Hume's Law and its criticism. Hume's Law, that one cannot derive an ‘ought’ from an ‘is’, is historically closely associated with the scientistic principle, which I shall label (1), viz. that social scientific propositions are logically independent of value positions. Hume's Law may then be stated as (2): value positions are logically independent of social scientific positions. And (1) and (2) may be represented as:

It is important to keep the two distinct, for nowadays (1), very much out of vogue in postmodernist thought, is quite often rejected, while (2) is still largely held sacrosanct. However, it will be seen that without a rejection of (2) as well, rejection of (1) injects a moment of arbitrariness into the social scientific process. I want to argue against (1), scientism, and (3), irrationalism (T

P), that,

pace Hume, it is irrational to prefer the destruction of the world to that of my little finger (i.e. against moral contingentism, or scepticism – a direct analogue of the problem of induction); and against (2), positivism, and (4), theoreticism (T → P), entailing moral actualism which makes akrasia impossible. More generally, I want to combat the dismissal of the descriptive or ontological grounds in virtue of which some belief or action is c...