1 INTRODUCTION

The digital economy and the splintering of economic space

In 2001, the first major transatlantic telesurgical operation was carried out: doctors in the United States removed a gall bladder from a 68-year-old woman in France by remotely controlling a surgical robot arm. The two medical teams were linked by a high-speed fiber-optic loop. The time delay between the surgeon’s movements and the return video image displayed on screen was less than 200 milliseconds (BBC News 2001; Marescaux et al. 2001).

The Dalles, Oregon, a community of 12,000 inhabitants on the Columbia River, has become a key nexus of the World Wide Web. Google has built there a major data center—thousands of interconnected servers—which benefits, like aluminum plants, from the abundant and cheap electricity supply (Spellman 2005).

In Ann Arbor, Michigan, operators at ProQuest, a digital archive company, scan microfilms of nine major US newspapers. Then, the copies are e-mailed to Chennai (Madras), India, where 850 employees of Ninestars Information Technology Ltd cut up and sort the images into articles suitable for Web search and reading. Salesforce.com Inc., a customer-relationship management (CRM) company based in San Francisco, subcontracts some typing to Digital Divide Data, a non-profit organization based in Laos and Cambodia, which has trained poor, and sometimes disabled people (Helm and Kripalani 2006).

These examples are a brief aerial survey of the splintering, but interconnected, economic space which is emerging in the Internet era. There remains virtually no place on earth, neither rural Oregon nor Cambodia, which cannot intrinsically get in touch—maybe in a subordinate way—with the globalized economy. This is the main objective of the present book: to inventory, describe, and explain the original features and dynamics—from both organizational and geographic viewpoints—which derive from the all-out intrusion of digital technology in the contemporary economy.

Splintered, yet connected

In many different ways, businesses are operating in a digital, interconnected space of flows (Castells 1996), that has permitted a fine-grained spatial division of labor, taking advantage of optimal combinations of (high) skills and (low) wages in various places around the world (Grossman and Rossi-Hansberg 2006; Scott 2006). This splintered economic space encompasses not only the production of tangible products but also many office-based tasks as paper is replaced by digital files (Blinder 2006). These files can contain food orders from drive-through lanes of distant restaurants (Richtel 2006) or scans of a patient in the US read by a radiologist in India (Wachter 2006b).

Until recently, the need to take a patient’s history and perform a physical examination, apply complex techniques or procedures, and share information quickly has made medicine a local affair. … To examine the heart, the cardiologist could be no farther from the patient than his or her stethoscope allowed, and data gathering required face-to-face discussions with patients and sifting through paper files. But as health care becomes digitized, many activities, ranging from diagnostic imaging to the manipulation of laparoscopic instruments, are rendered borderless. The offshore interpretation of radiologic studies is proof that technology and the political climate will now permit the outsourcing of medical care.

(Wachter 2006a: 661)

As it takes advantage of a growing array of digital technologies, the geography of any business becomes more complex and difficult to locate. Managers and entrepreneurs who seek the ideal location, as well as analysts, scholars, and policymakers who seek to understand and predict them, confront a more complex geography of the global economy. As digital processes have permeated the entire value chain, they have permitted a countless series of tasks amenable to remote treatment (Blinder 2006). This “great unbundling” of tasks has sparked fears that nearly all jobs will disappear from high-wage countries (Baldwin 2006).

Even high-end jobs are not secure. Several hundred US hospitals use overseas teleradiology services, such as Teleradiology Solutions, NightHawk Radiology Services, and Virtual Radiologic (Wachter 2006b). In electronic intensive care units (ICUs), “off-site intensivists monitor patients by closed-circuit television. Streams of physiological data appear in real time on a remote screen, allowing the off-site physician to advise local providers, sometimes even entering orders remotely into the hospital’s computer system” (Wachter 2006a: 663). Wachter (2006b: 663) quotes a US radiologist: “Who needs to pay us $350,000 a year if they can get a cheap Indian radiologist for $25,000 a year?”

However, digitalization has not created an economy that has become completely footloose in which any task can be done anywhere. Yet this is the hype that has been promised—or threatened—by many pundits. A state of confusion surrounds the digital economy. Oversold and characterized by hype, the long-awaited paperless office, picture-phones in every home and office, and the global village have not materialized. In part, this is because many different views have coalesced around the information society, the digital economy, the network economy and other labels for the new, technology-based world. Among the recent examples of hype are two books whose titles are frequently mentioned to capture the phenomenon: The Death of Distance (Cairncross 2001) and Global Financial Integration: The End of Geography (O’Brien 1992).

A more nuanced analysis of the social, economic, and geographical changes underway leads Kotkin (2000) to observe that “the new geography” is highlighted by the growing importance of “sophisticated consumers of place” (Knight 1989: 237). In fact, more than place or places are consumed, as networks and the “space of flows” also are evaluated and consumed in sophisticated ways (Castells 1989). We prefer to generalize the phenomenon to companies as well as people, all of whom have become sophisticated consumers of space.

Even though downloaded files (such as music, video, and information from web pages) are perceived as “free” to many users, because it is very easy to retrieve information across long distances almost instantaneously (depending on the last mile link to one’s computer or mobile phone), distance is not “dead.” Cairncross (2001), whose book is cited routinely in this regard, recognizes that the story is more subtle. “The death of distance loosens the grip of geography. It does not destroy it” (Cairncross 2001: 5). It is not a case of technological determinism, with information technologies (IT) creating a global village. The falling cost of communication has not been felt equally everywhere. Large cities continue to dominate both in network connections and in the agglomeration of face-to-face activities for which “the tyranny of proximity” has replaced the tyranny of distance (Duranton 1999). Poor people and regions continue to lag behind as new technologies flow first into wealthy regions. For the individual, the ability of the telephone to permit voice and image communication over distance has evolved—thanks to both wireless technologies and the Internet—into new “personal mobilities” (Kellerman 2006) and new consumer power (Markillie 2005).

The diffusion and the convergence of digital technologies

It is difficult to avoid hype or exaggeration in the discussion and analysis of the continuous series of events which constitute the so-called “digital revolution.” The evolution of telecommunications, discussed in greater detail in Chapter 3, has been a continued improvement of communications technologies since the telegraph and the radio in the nineteenth century (Arnold and Guy 1989; Cukier 2007). The computer was invented in the 1940s, and has benefitted since from a continuous improvement process. But these technologies remained separate until the early 1990s, at least in the public’s eyes.

To understand the hype that arose in the 1990s around the concept of IT (information technology)—after all, telegraph and Gutenberg’s printing press were also IT—we must consider the close interlinkage of three processes:

- ■ the computerization of the society, thanks to the production of cheap personal computers (PCs) operating user-friendly interfaces (itself a consequence of the materialization of “Moore’s law” in microprocessors);1

- ■ the convergence of computers and telecommunications (Steinbock 2003; Yoffie 1997);

- ■ the irresistible diffusion of the Internet and the spread of the World Wide Web, its most popular application.

Actually, at least four formerly distinct industries—computers, communications, software, media and entertainment—have converged into a galaxy of overlapping, digitally enabled industries which share common technical standards and channels. But a few business sectors, we suggest in a later section, actually ignore the digital convergence and remain largely un-digitalized.

The analysis of this evolution faces typical “chicken-and-egg” problems. The Internet would not have become so popular if businesses and households would not have gotten access en masse to cheap computers and network technologies such as cable modems and digital subscriber lines (DSL). Media and commerce would not have become electronic—in part—without the commoditization of PCs and the Internet. In turn, the richness of the content and applications available now via the Internet is a powerful driver towards more computers and more connections at home, in schools, in enterprises. The system of interlinkage should be extended further. Computers, together with other digital devices such as flat-panel TVs, cameras, and wireless handsets, have become commodities because they are the outcomes of a globalized production system, which includes low cost countries, and could not be coordinated without a wide range of IT applications. The digital convergence should be regarded as the emergence of a huge, worldwide value network (see Chapter 4), which sees a continuous process of creation of new companies, new products, and new niches of value-added creation.

The phenomenon of convergence is clearly visible in the rise of “triple play” bundled subscriptions, which give customers access to the Internet, telephony (Voice over Internet Protocol or VoIP), television, and a roster of home media and entertainment services, from the same copper or fiber-optic line. This tendency materializes in “device convergence”: desktop and laptop computers, mobile phones, television sets, and game consoles are all able to access the Internet, display messages and video, and store information (Standage 2006). The latest versions of advanced mobile telephone handsets, which incorporate computing capacity, Internet access, e-mail, photo and video camera, and even video display, perfectly epitomize both the convergence and the unprecedented degree of informational ubiquity it gives to “connected” people (Figure 1.1).

In some way, the latest technology has made real some images and metaphors which have long been associated with science fiction. The design, marketing and servicing of these technologies have generated an enormous industry, with real impacts on producers, consumers, and actual economic effects on places and regions.

Digital technology is spreading throughout the entire economy. Computers and telecommunications are mainly enabling technologies, which serve downstream industries in both manufacturing (e.g. automobiles, aerospace, textiles, and electrical equipment) and services sectors (transport and travel, finance, retail). Even industries in the primary sector, such as farming, fishing, and mining, rely now on computers, digital apparatus and software, and advanced telecommunication services. Fishermen and farmers use radar, sonar, and global positioning systems (GPS). Farming and forestry are important users of remote sensing and geographic information systems (GIS). Oil prospecting could not be performed without powerful computing capacity.

The digital economy: a definition

The digital economy represents the pervasive use of IT (hardware, software, applications and telecommunications) in all aspects of the economy, including internal operations of organizations (business, government and non-profit); transactions between organizations; and transactions between individuals, acting both as consumers and citizens, and organizations. … The technologies underlying the digital economy also go far beyond the Internet and personal computers. IT is embedded in a vast array of products, and not just technology products like cell phones, GPS units, PDAs, MP3 players, and digital cameras. IT is in everyday consumer products like washing machines, cars, and credit cards, and industrial products like computer numerically-controlled machine tools, lasers, and robots. Indeed, in 2006, 70 percent of microprocessors did not go into computers but rather went into cars, planes, HDTVs, etc., enabling their digital functionality and connectivity.

(Atkinson and McKay 2007: 7)

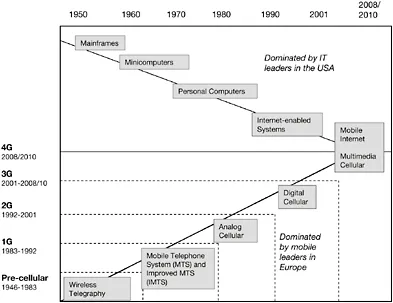

Figure 1.1 Convergence in wireless communications

Source: Steinbock 2003

As IT has become cheaper, faster, better, and easier to use, organizations continuously find new and expanded uses for IT, creating digital applications connected—increasingly wirelessly—that have become ubiquitous and central to economic and social activity (Atkinson and McKay 2007; Cukier 2007). However, not all industries and regions worldwide have reached the same level of IT adoption. Farmers and fishermen in developing countries are not computerized. However, digital devices (embedding “chips and bits”) are becoming almost ubiquitous. In sub-Saharan Africa, where most of the world’s poorest countries are located, mobile telephones are becoming a commodity, and are commonly used by merchants to conduct commercial transactions. In some way, we are on the verge of an “Internet of things,” according to the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) (2005).

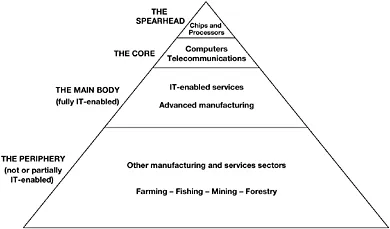

Consequently, the digital economy can be described as a pyramid (Figure 1.2). The top section—the “spearhead”—includes the products of the silicon foundry and semiconductor industries. Itself not a large sector, it is critical, because its products are at the core of computers and electronic components, which are embedded in an increasingly far-reaching range of products, including consumer electronics, automobiles, machines and industrial equipment, heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems, and household appliances. Major distribution chains such as Wal-Mart have started to attach “smart tags” (RFID or radio frequency identification devices) on packages of basic goods sold in supermarkets.

The second level of the pyramid, below the spearhead, is comprised of the computer and telecommunications industries, both manufacturing and services. These industries may be regarded at the “core sector” of the digital economy, because this sector enables the working of the lower parts.

The third level represents the “main body” of the digital economy, including both manufacturing and services activities which rely heavily—sometimes almost exclusively—on digital technologies. A large fraction of people in these industries spend most of their working time on computers and telecommunications devices. In the service sector, we must mention: electronic commerce, media and entertainment, and IT-enabled business services (such as call centers and shared service centers), and financial services. In the manufacturing sector, we can identify the IT-intensive sectors where “product lifecycles” (a concept explained in Chapter 4) are fully or partially IT driven, such as the automobile or aircraft industries. However, even in the most advanced industries, digitalization varies among departments and regions. Companies have departments that are fully computerized (R&D, design, data treatments), but others which work using more “traditional” means. In a typical automobile company such as Renault, 50 percent of the whole workforce is in front of a computer either full-time or part-time. In retail banking (where 100 percent of the workforce is computerized, at least in developed countries), employees in back-office functions perform fully IT-enabled tasks (which are increasingly subjected to offshoring), while front-office people still have face-to-face meetings with clients. The logistics industry and the medical sector also belong to this category.

Figure 1.2 The pyramid of the digital economy

Source: Authors’ own research

The base of the pyramid is made of sectors whose digitalization remains almost nonexistent, or at most partial, as they are slowly permeated by digital technology. This is the case for a large part of the farming sector, especially in developing countries. In home and consumer services, as well as in public services, a vast range of people rarely or never use a computer, such as housemaids, garbage collectors, hairdressers, and police officers. From kindergarten to university, the use of computers and the Internet in education is very diverse, varying among levels, disciplines, and regions. For example, primary schools in Finland are all IT-equipped, but some university professors in arts and humanities, in almost every country, have never used a computer. Because face-to-face contact between students and teachers remains the base of teaching, the main body of the educational sector is not in the core of the digital economy, even if it is increasingly p...