![]()

1

The tank and the tortoise

Theorists soon found out how difficult the subject was and felt justified in evading the problem by again directing their principles and systems only to physical matters and unilateral activity. As in the science concerning preparation for war, they wanted to reach a set of sure and positive conclusions, and for that reason considered only factors that could be mathematically calculated.

(Carl von Clausewitz, On War)

When you emerge from the desert, your eyes go on trying to create emptiness all around; in every inhabited area, every landscape they see desert beneath, like a watermark.

(Jean Baudrillard, America)

In the high Mojave Desert, a pale imitation of trauma brought memories of my grandfathers’ wars back to the surface. Except for the odd schoolyard fight, and getting beat up in a demonstration in Paris, I had managed to avoid anything remotely as violent as a battlefield. Yet on a desert hilltop, images of my grandfathers’ wars rose and merged with the heat, noise, and immediacy of the approaching battle below.

I first heard of Fort Irwin at the beginning of the end of the Cold War, in a brief newspaper report about a visit made by the first President Bush. He had come by in February 1989 to observe a war game pitting the Third Armored Brigade of the Ninth Infantry Division against the Ninety-seventh Krasnovian Motorized Rifle Brigade. On the day of Bush’s arrival, President Mikhail Gorbachev had done the unthinkable and announced an

end to the Soviet Communist Party’s monopoly on power. Outfitted in camouflage jacket, pinstripe trousers, and wing-tip shoes, Bush called a five-minute time-out to the war game to let the 2,689 soldiers below know the good news. By radio link he informed them from a ridge above that “we are pleased to see Chairman Gorbachev’s proposal to expand steps toward pluralism.” He pledged, however, “not to let down our guard against a worldwide threat.” Inspired, the Krasnovians, as they are wont to do at the National Training Center (NTC), made borscht out of the Third Brigade. Bush didn’t get to see the Soviet victory; he had already left for the Livermore Labs for a briefing on Star Wars, another system designed to defeat factual forces by fictitious ones.

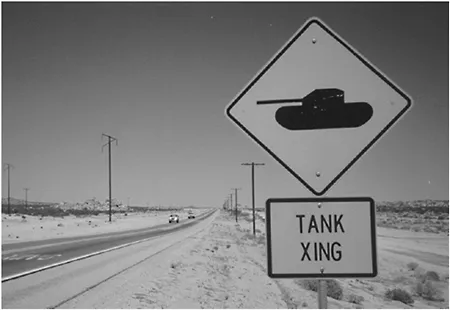

Five years later I decided to make Fort Irwin the first stop of my virtual pilgrimage, to see how the future of warfare was being written in the desert sands of the Mojave. Created in 1981, Fort Irwin’s purpose is to take American troops (and NATO allies) as close to the edge of war as the technology of simulation and the rigors of the environment will allow. My trip got off to a bad start. I was on a seemingly endless two-lane highway; it was too early, too dark, and, not wanting to give the public affairs officer another opportunity to explain what oh-five hundred meant, I was driving too fast to catch the first yellow warning sign. Fortunately I spotted the second one, just before the real thing crossed the road, of a black silhouette of a tank and underneath, TANK XING.

Digitally enhanced, computer-accessorized, and budgetarily gold-plated from the bottom of their combat boots to the top of their kevlar helmets, the 194th Separate Armored Brigade from Fort Knox, Kentucky, had come to Fort Irwin for Operation Desert Hammer VI. The first “Digital Rotation” of troops, this experimental war game was developed to show the top brass, a host of junketing congressmen, any potential enemies, and us—an odd mix of media—how, in the words of the press release, “digital technology can enhance lethality, operations tempo and survivability across the combined arms team in a tactically competitive training environment.” In other words, the task force had come wired, to kill better, move faster, and live longer than the enemy.

In my mind, the pre-war game hype triggered all kinds of skeptical questions. Was digitization going to cut through the fog of war, or just add more layers of confusion? Could computers control the battlefield, or would the friction of war conquer the computers? Would the digital buzz drown out ethical questions? Would these new technologies further distance the killer from the business of killing?

These are hardly unfamiliar questions, even for the army. Back when messages traveled at the speed of a horse and overhead surveillance meant a hilltop, the Prussian strategist, Carl von Clausewitz, warned in On War against the arrogance of leaders who thought scripted battles would resemble the actual thing: “The general unreliability of all information presents a special problem in war: all action must, to a certain extent, be planned in a mere twilight, which in addition not infrequently—like the effect of fog or moonlight—gives to things exaggerated dimensions and an unnatural appearance.”1 Would digitization, the merging of the infospace with the battlespace, render Clausewitz’s famous dictum obsolete? Understandably, Clausewitz didn’t have much to say about infowar, netwar, cyberwar, and the like. He did, however, dismiss all contemporary attempts to use “positive theory” and technical knowledge to close the gap between planned and actual war. In his words, models, systems, and codes of war were finite syntheses, while war was inherently complex, open-ended, and interactive. To fight the digital hype and the illusion of a technological fix, I intended to follow his advice: apply, in his words, a “critical inquiry” that “poses the question to what are the peculiar effects of the means employed, and whether these effects conform to the intention with which they were used.”

Operation Desert Hammer, however, was to turn Clausewitz on his head. Not only did the strategic effects of digitization prove to be very peculiar and to bear little conformity with the advertised intentions of the army; they seemed destined to replace an increasingly irrelevant nuclear balance of terror with a simulation of digitized superiority: call it the new cyberdeterrent.

By the end of the first day, after chasing the black-bereted Krasnovians through the Whale Gap and, lo, into the Valley of Death, watching them kick American khaki all the way to the John Wayne Hills, I was left with no better sense of whether the professed claims for the digitized army were true or not. One reason is that the use of digitization was not readily apparent—or even visible. So we largely had to rely on the claims of the glossy brochures and our voluble briefers and handlers. Since these claims often came in packaged phrases and punchy sound bites, my skepticism kicked in early. Many had the ring of a corporate advertising campaign. Top of the list, with budget cuts clearly on everyone’s mind, was “Smaller is not better: better is better.” Others sounded like a hybrid of Nick Machiavelli and Bill Gates—“Win the Battlefield Information War”—or of a New Army for the New Age—“Project and Sustain the Force.” Analogies proliferated like mad: digitization is equivalent to the addition of the stirrup to the saddle, or the integration of helicopters into the army. By the second day I could fathom the meaning, but not test the truth of some statements, like “digitization will get us inside the enemy’s decision-making cycle.” And I could only think of a sky full of frogs with wings when one of the public affairs officers boldly declared that “If General Custer had digitization, he never would have had a last stand.”

On paper, however, the combination of brute force and high tech did appear formidable. At the high end of the lethality spectrum there was the improved MIA2 Abrams main battle tank, carrying an IVIS (Inter-Vehicular Information System) which could collect real-time battlefield data from overhead JSTAR aircraft (Joint Surveillance and Target Attack Radar System), Pioneer unmanned aerial vehicles equipped with video cameras, and global positioning satellite systems (GPS) to display icons of friendlies and foes on a computer-generated map overlay. At the low end, there was the “21st Century Land Warrior” (also called “warfighter,” but never “soldier” or “infantryman”), who came equipped with augmented day and night vision scopes mounted on his M-16, a GPS, 8 mm video camera, and one-inch ocular LED screen connected by a flexible arm to his kevlar, and an already-dated 486 Lightweight Computer Unit in his backpack, all wired for voice or digital-burst communication to a BattleSpace Command Vehicle with an All Source Analysis System that could collate the information and coordinate the attack through a customized Windows program. “Using the power of the computer microprocessor and digital electronics,” digitization was designed to be a “force multiplier”: the “horizontal integration of information nodes” and the “exchange of real-time information and data” were going “to establish friendly force dominance of enemy forces.” In short, the army was creating a C4I bundle (command, control, communication, computers, and intelligence) of soft-, hard-, and wetware for the coming information war.

I wondered what Clausewitz, who warned that “a far more serious menace is the retinue of jargon, technicalities, and metaphors,”2 would have made of this press packet. Or what was handed out in the predawn along with it and our helmets: two sets of release forms with lots of fine print. I sensed the disdain of my media cohort, a reporter and photographer from the Army Times, because I insisted on reading the release before signing it. It wasn’t the physical harm stuff that bothered me (that much); it was the clause about permissible photo-ops. It seemed to suggest that the army could refuse the taking of any staged photographs. Since I interpreted all of what we were about to see as staged, couldn’t this amount to a blanket restriction? A higher-up was called over, who assured me that this meant only that I could not request a rerun of a battle scene in case I missed it the first time around. Dan Rather probably would have demanded rights to a director’s cut, but I signed the thing before I used up my quota of goodwill. When the motto miasma met the fog of war on the first day of battle, the fog seemed to win out—especially since it came amply supplemented by sand, dust, and smoke (the latter provided in copious amounts by M54 pulse-jet smoke dischargers). Our handler, Major Childress, already introduced, did his best to explain what was going on around us. After leading our small convoy of three High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicles (HMMWV), known as “Humvees,” to that fine hillside perch to watch the dawn battle unfold, he provided a running commentary for what we could see—and also what we could hear as we eavesdropped on the radio traffic among the combatants, and heard those reports of fratricide or “friendly fire.”

Nobody wanted to go on record to say how the battle started. I later learned from a defense industry rep squirreled away in a back room that it began out of sight (and out of the public eye) with the launch of a cruise missile off the Californian coast; it landed somewhere on the live-fire range (rather than, say, a Las Vegas casino). For us, the battle began with an array of Black Hawk and Apache helicopters coming in so close to the deck that we looked down from above as they flew by. My first thought was of the two U.S. helicopters mistakenly shot down by U.S. fighter planes over Iraq the week before the exercise, a deadly case of “friendly fire.” The first Black Hawk, equipped with external fuel tanks, did bear a resemblance to a Soviet Hind. I filed away the question as an F-16 followed it, sweeping over our hill and dropping flares to confuse possible ground-to-air missiles. Had the pilots that shot down the helicopters ever trained against Black Hawks pretending to be Soviet Hinds?

The level of confusion rose as loud bangs joined the visuals. An M-22 simulator round, about the size of a fat shotgun shell, went off as a nearby Stinger crew fired at an F-16. Then came the white plumes of “Hoffmans,” blanks that simulate the flash and bang of tank and artillery fire, spreading across the battlefield. The arrival of the main show was signaled by tracks of dust on the horizon. Tanks, Humvees with TOWS (Tube Launched Optically Tracked Wire Guided missiles), and armored personnel carriers came out of the wadis with a burst of speed. As the Opposing Forces (OPFOR) began to mix it up with the visiting Twenty-fourth Mechanized Division, vehicles bearing the orange flags of the war game observer/controllers darted in and out as they tallied up the kills. They depended on the MILES, or Multiple Integrated Laser Engagement Systems (first developed by Xerox Electro-Optical, now better known as laser tag), which were attached to every weapon from the M-16s to F-16s. Configured to match the range of each weapon system, the Gallium Arsenide laser, for example, on the M1A2 main battle tanks could reach out and touch someone at 3,000 meters. Hits and near misses were recorded by the sensors on the vests and belts that circled soldiers and vehicles alike, and transmitted by microwave relay transmitters back to computers in the “Star Wars” (also known in some circles by the more imperial-sounding “Dark Star”) building from which the battle was run. From our hillside we could see the flashing yellow strobes of the MILES sensors spread across the battlefield as the OPFORS cut through the American forces. Simulation-hardened and terrain-savvy, the “Krasnovians,” as they are, post-Cold War, nostalgically still called, rarely lose—even on the rare occasions when they must redial the threat and take on the garb and tactics of the “Sumarians” (Iraqis) or “Hamchuks” (North Koreans).

Suddenly we received a radio order to move: our position was about to be overrun. Events were moving more swiftly than commands: the Krasnovian tanks had already crested the ridge and were heading for us. Sensing a good photo-op, I brought my camera up to greet them. It wasn’t until the tanks were within smelling distance that I realized everyone else had scurried, for good reason, to the other side of the hill. I found myself alone and in a very precarious position.

Synapses fired and hormones mixed into a high-octane cocktail, telling me to fight or take flight. I did neither. I froze, feeling that terrifying yet seductive rush that comes when the usual boundaries, between past and present, war and game, spectator and participant, break down. The catatonia was short; but caught in an extraordinary balance between real and pretend states of danger, I experienced a strange, dreamlike synchronicity. I was there, but not there. The threat was unreal, distanced by high technology and the simulation of war; and yet, with the approaching tank, all too real. I could imagine yet deny death, my own as well as others. Detached and yet connected to a dangerous situation by a kind of traumatic voyeurism, I watched myself watch the tanks bear do...