1

Introduction

On the steps of the Old Courthouse in downtown St. Louis, Missouri, a crowd of people gathers at a rally in support of public education. The Literacy for Social Justice Teacher Research Group (LSJTRG) and the ABC’s of Literacy Group1 have organized this rally to voice concerns about the privatization of education in St. Louis as it affects the rights of all people (locally and globally) for equal access to quality education. Across the street from the Old Courthouse a national conference of adult educators (Commission on Adult Basic Education) is taking place. We leaflet at the conference for attendees to join us at the rally, knowing that our struggle for education includes both K-12 and adult education.

We are here today to reaffirm the importance of education as a civil right—as the cornerstone of a strong democracy—not as an entitlement program or as a commodity in the market place. We are here today to call for a democratization of public education—not a privatization of public education.

Rebecca Rogers, co-founder of LSJTRG (with Mary Ann Kramer), opens the rally with comments that frame the importance of educators across the lifespan uniting around principles of democracy and civil rights. “The idea for this rally emerged out of a series of dialogues and actions around literacy education that have taken place in St. Louis. Educators across the lifespan have been working on realizing the connection between literacy and freedom.”

Ora Clark-Lewis, an adult education teacher and member of LSJTRG, makes the connection between the struggle for equal education today and 200 years ago when Freedom Schools were created in St. Louis in resistance to a state law forbidding enslaved African Americans to read and write.

Donna Jones, elected school board member, gives an update on the court case over the state take-over of the St. Louis Public Schools: “We are taking our case

1. ABC’s of Literacy stands for Acting for a Better Community and includes a group of adult education teachers and educators who organize around literacy education for freedom. At different points, the paths of LSJTRG and ABC’s cross, such as in planning this rally (Acting for a Better Community Organizing Team, 2008).

to the state Supreme Court and we will be heard later this summer. The fight is not over and we are asking that you stand and you fight with us.”

A local high school teacher and a student share the song they wrote called “Democracy Anthem” to protest the state take-over of the public schools. Between speakers the crowd claps and cheers.

Extending to a global focus, Cynthia Peters from The Change Agent states,

We need nothing less than all of our minds to solve the problems we are facing today. We need broad based social change movements with deep roots in all communities. This means that educators need to work with antiforeclosure, environmental justice, immigrant reform and peace groups. Together we can stop the militarization and corporatization of our daily lives. We need education but we don’t need just any kind of education. We need an education that empowers and that frees our mind and helps us unfold as human beings.

An adult literacy student and intern reads the Declaration Statement—a statement that calls for united action among advocates for public education in the face of unjust educational reforms. Over 200 signatures were collected on the declaration statement, including participants at the conference, and will be sent to local, state, and national elected officials (see Appendix 1). Other speakers, including national adult education advocates, make connections between the ongoing wars and the privatization of public services, including education.

On the sidewalk, people gather together holding signs that read “Books not Bombs,” “Literacy is a Civil Right,” “Our Schools are not for Sale,” and “Defend Public Education,” to listen to the speakers and music, and to participate in the symbolic actions. They wave their signs at the rush-hour traffic and receive honks of support. The rally ends with the drumming of Thunderheart, a traditional Native American drumming group, accompanying the posting of the mini-protest signs on a public display board. Later, the nightly news reports, “A group gathers in downtown St. Louis to voice their support for public education.”

This is a gathering of teachers—across the lifespan, of community activists, of union members, of candidates running for political office, adult learners, parents and elected officials. Despite the pressures of silencing of teachers, outsourcing of curriculum, high-stakes standardized tests, reduced education budgets owing to the war in Iraq, teachers, parents, and students are standing together to call for justice. On the steps of the Old Courthouse, the boundaries between traditional grade levels, between teacher and activist, and between the school and the street disappear. Here, teachers use their voices to defend public education and stand in solidarity with educators across the nation and world.

Several weeks before, members of LSJTRG and ABC’s gathered to plan the rally following Meredith Labadie’s workshop on Teaching for Social Justice in Reading and Writing Workshops. During this and subsequent meetings we brainstormed slogans for the signs, generated a list of speakers and musicians, designed fliers, wrote a press release, obtained a permit for the rally, and circulated announcements and leaflets. We thought of ways to make the rally interac-tive and participatory, including circulating a declaration calling for education to be considered as a civil right and having mini-protest signs available where people could pen their own message.

The rally captures the essence of the LSJTRG—the power and potential of a group of educators working together—inside and outside the classroom—to use literacy and language to make changes in society. Many of the teachers who planned and participated in the rally are members of LSJTRG. Many of them appear in the pages of this book. These teachers work in different schools and in different districts. Their students vary in age and range from working-class European Americans to middle-class African Americans to adult immigrants. Whether in or out of the classroom, these teachers are committed to educational practices and outcomes that contribute to freedom and justice—in short, critical literacy education. While exploring social class, gender, sexuality, race, the environment, or human rights with their students and collaborating with other educators to plan a workshop or rally, these educators draw on a set of tools to interrogate social practices, sort through multiple agendas encoded in texts, and to collaborate on ways of acting in more socially just ways.

The LSJTRG is a grassroots, teacher-led professional development group dedicated to exploring and acting on the relationships between literacy and social justice. The intersecting stories of this group of educators are told in the pages of this book. Along the way we set forth a lifespan perspective on critical literacy education, one that draws on popular education and can be utilized across the lifespan.

This project—both the book and the ongoing cultural work of our group—was conceived in the spirit of engaged scholarship. Since 2001, we have been organizing, holding public meetings around social justice issues, conducting inquiry in our classrooms, sharing our analyses, and participating in social justice events. We believed there was something unique about our work together. It was not until 2005 that we learned that other teacher activist groups like our own were springing up all over the United States in cities such as New York, Chicago, and San Francisco. We were busy building a space where educators could network, learn, and grow with each other. When we looked up, we realized we were not alone in the journey.

We believed there was something very generative about our work together that could serve as a model for other educators, researchers, policy-makers, and activists who are also involved with grassroots educational reform. We decided to formally document our process of working together for educational change. We extended an invitation to people involved in the group to a summer institute to explore the process of writing a book to document our experiences, as individual educators and as a social justice group. Several of the teachers at the institute had already conducted inquiry projects in their classroom that they wanted to write about. Others had not begun the process yet. The institute was a place for us to brainstorm, share, and organize our thoughts.

Many drafts later, we arrive at a book that offers a snapshot of our journey—as individuals and as a group. As educators and citizens who believe education is vital to a healthy democracy, we embarked on this work as a form of praxis— theory, practice, reflection, and action (Croteau, Hoynes, & Ryan, 2005). Our research allowed us to delve more deeply into the public domain; our activism inspired our writing and provided us with a grassroots perspective. This book joins these educators’ stories with the history and practices of the teacher inquiry group, providing a twofold emphasis on critical literacy education.

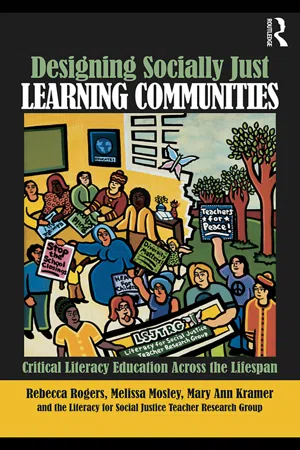

Photo 1.1 LSJTRG participants at the Defend Public Education Rally.

Literacy Education, Freedom, and Democracy

In our work as literacy educators—with GED, high school, elementary, and teacher education students—we are constantly reminded of the importance of guiding our students as readers, writers, and thinkers while at the same time educating towards social responsibility. Children, adolescents, or adults who have had, or are expected to have, the most difficulty with literacy are commonly the most oppressed by literacy. It is these students and their teachers who stand to benefit the most from developing critical literacy practices within socially just learning spaces.

Critical literacy education takes many shapes and forms (for reviews of critical approaches to literacy see Collins & Blot, 2003; Janks, 2000; Luke, 2000; Muspratt, Luke, & Freebody, 1997; Street, 2003). When critical frameworks guide literacy education, they are referred to as critical literacy or participatory literacy education. Critical literacy education has deep roots in the struggle of historically marginalized people to gain literacy and political power (e.g. Clark, 1990; Freire, 1970a; Horton, Kohl, & Kohl, 1997). Because of the links between literacy and freedom, access, and economic mobility, literacy has always been political and central in struggles for freedom (e.g. Monaghan, 1991; Moore, Monaghan, & Hartman, 1997; Prendergast, 2003). Critical literacy education includes practices that disrupt or critique dominant knowledge–power relationships that perpetuate unequal gender, race, and class relations and instead center dialogue, debate, and dissent, features of a democracy. We envision critical literacy education as the vehicle for building more democratic communities.

There are many good introductions to the theory and practices of critical literacy (e.g. Lewison, Leland, & Harste, 2008; Stevens & Bean, 2007; Vasquez, 2003) and demonstrations of critical literacy in classrooms (Cowhey, 2006) and out-of-school spaces (Comber, Nixon, & Reid, 2007; Morrell, 2008). We have accounts of how children in elementary classrooms practice critical literacy (e.g. Comber, Thomson, & Wells, 2001; Henkin, 1998; Lewison, Flint, & Van Sluys, 2002; Powell, Cantrell, & Adams, 2001; Sweeney, 1997; Vasquez, 2004) as well as accounts of critical literacy in middle and high school (e.g. Morrell, 2008; Myers & Beach, 2004; Rogers, 2002), adult education (e.g. Brookfield, 2005; Degener, 2001; Rogers & Kramer, 2008), and teacher education (e.g. Comber, 2006; Dozier, Johnston, & Rogers, 2005; McDaniels, 2006). Our work departs from earlier work in our dual emphasis on critical literacy education—within classrooms across the lifespan and within the context of a teacher-led professional development group. Here, we sort through what we mean by critical literacy education—discussing each of the terms associated with the concept in turn, “critical,” “literacy,” and “education.”

Critical

I am linking the struggle of men and women of color as a common struggle—and teaching implicitly that feminism is a set of issues and actions that is relevant in the lives of men as well as women.

(Carolyn Fuller, Adult Education and Literacy Teacher)

What does the term “critical” mean in critical literacy education? We use the construct of “critical frameworks” to refer to the myriad ways in which educators practice critical literacy to create socially just learning spaces. There is no one critical framework or set of methods or approaches that characterizes a critical teacher. A critical framework includes an analysis and critique of systems of oppression and the tools for social action. See Table 1.1 for a list of the social justice issues that are explored throughout this book.

Critical frameworks start from the assumption that literacy learning includes a struggle over power and knowledge (Edelsky, 1999; Freire, 1970b; Janks, 2000; Luke, 2000; Richardson, 2003). In Carolyn’s voice above, we see that struggle is a common theme in society, and is therefore in our educational frameworks. In the sense that knowledge is never neutral but is defined by those who have access to resources, critical education practices seek to redistribute power/knowledge relationships. This redistribution means recognizing, challenging, and rebuilding relationships that are fundamentally constructed out of the fabric of oppression. To do this, we need multiple frameworks to notice and name oppression. Thus, we recognize the multiplicity of critical perspectives from anti-racism, class-based instruction, culturally relevant instruction, multicultural education to feminist teaching. Our stance is that they all add to the struggle for human liberation.

Table 1.1 Critical Literacy Education: Infusing Social Justice in the Literacy Curriculum

Underlying each of these frameworks is a set of values that conflicts with the values of dominant institutions. For example...