1.1

Introduction

Children and the way they live in places, build relationships, and learn are not always the primary starting point of reference guiding the various phases of school design and construction.

(Vecchi 1998: 128)

Can the design process accommodate the perspectives of the youngest citizens? Can a desire to listen to young children’s views and experiences lead to more ‘people-centred’ (Fielding 2004: 213) learning communities which can provide living spaces for adults and children?

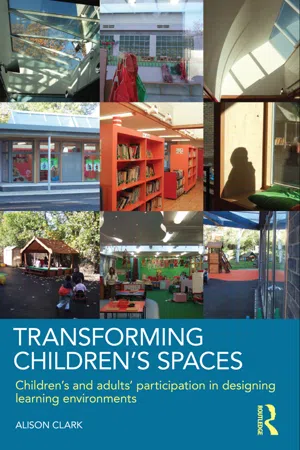

This book sets out to explore how young children can play an active role in the designing, developing and reviewing of early childhood centres and schools. Focusing on children from three to seven years of age, this book describes the adoption of participatory research methods and visual narratives, particularly in real-life building projects. A key objective is to explore how young children’s views and experiences can inform both the planning of new provision and the transformation of established provision.

Bringing young children into the frame raises their status from an often invisible object of design to an active, visible presence within this complex process. Seeking ways to make young children’s perspectives visible has demanded a search for a common language on which to base this model of dialogue. Photography has been one of the means to make accessible some of the knowledge children hold about their environment. It has become a key tool in extending communication between the different players involved.

Early childhood centres and schools are not exclusively environments for children, but are shared spaces for children and adults. This book explores how other perspectives or voices, including those of practitioners and parents within these institutions, can be given currency throughout the design process.

Rather than begin by looking at hopes for future spaces, this book firmly roots discussions about possible spaces in increasing understandings about children’s existing environments. What objects, features and people do young children draw attention to or appear to ignore? What issues may this raise in terms of priorities in design?

Completing a new building or transforming an existing environment only marks a stage in an ongoing dialogue between children and adults. This book examines children’s and adults’ views and experiences of their new environments using their own visual narratives for a catalyst and point of exchange. This model of dialogue has implications beyond the design process. It implicates wider questions about participation, learning and democracy.

Part I introduces the theoretical and methodological tools which underpin this exploration of involving young children and adults in changes to their learning communities. Chapter 1.2 begins with an introduction to the theoretical approaches. This is followed by an introduction to the research case studies which inform the remaining chapters. This part ends with an introduction to the methods – the Mosaic approach (Clark and Moss 2001; 2005) – which provide the principles and tools for constructing the narratives to facilitate exchange within the design process.

Part II focuses on gathering children’s narratives about existing, possible and new spaces. Detailed examples of the methods in action are given. This leads to a discussion of the major themes which emerged about the young children’s perspectives of their environment, including some surprising insights about scale and perspective and personal spaces. This part ends with a chapter (Chapter 2.5) on temporal spaces which investigates how young children’s narratives about spaces may change over time.

Part III explores facilitating exchange between young children and adults within the design process. Chapter 3.2 examines how making young children’s perspectives visible can open up debate within learning communities and among practitioners and parents about shared environments. This includes a detailed account of how a multi-agency team in a children’s centre used the Mosaic approach to review the completed building. Chapter 3.3 illustrates direct and indirect engagement between young children, practitioners and architects at different stages of the design process, from initial discussions to post-occupancy reviews.

Part IV discusses possible implications of adopting the model of dialogue described in this book in terms of the design process, learning communities and research with both children and adults. This model of dialogue is underpinned by constructing narratives. Can these ways of communicating across generations and professions contribute to more schools and early childhood institutions becoming living spaces for children and adults, attuned to each person’s capabilities and needs? Does a role remain for the researcher?

1.2

Viewfinders

I believe that education, therefore, is a process of living, and not a preparation for future living.

(Dewey 1897: 77)

Introduction

‘To picture a world, a variety of worlds’

There is a children’s storybook by Hiawyn Oram (1984) entitled In the Attic. A young boy is at home and bored. He decides to climb an imaginary ladder into his attic. This leads to the discovery of new spaces and friends. One illustration shows the boy leaning out of a window which has appeared in the sky, gazing onto a new landscape. He is surrounded by other window frames, each of which shows other spaces. The boy continues on his way, carrying one of the frames under his arm. How do young children see their world? What images do they carry round with them in order to make sense of new spaces, people and objects? How equipped are practitioners who work each day with children? How equipped are architects who design learning communities to engage with these perspectives?

The account which follows is not a static narrative, but a series of multiple images and accounts which attempt to reflect the complex reality of the landscapes in which young children spend increasing amounts of time. I have found encouragement to pursue this bringing together of images, both visual and verbal, from several writers. Psychologist Oliver Sacks describes a similar desire in the preface to his book Awakenings (1973; 1990). Sacks’ account is a narrative about the effects of a new drug treatment on patients suffering from ‘sleeping sickness’. He describes how he could have produced a clinical account of the drug trials. However, he did not desire to create a static account. He desired to create a moving image of the lives of the patients:

I am interested, like Sacks, in picturing a world, a variety of worlds – the landscapes of being in which young children reside. This requires ‘an active exploration of images and views’, as Sacks suggests, and ‘a continual jumping-about’ between different perspectives and between different research tools. The complex task of picturing these diverse worlds has been shared with young children and adults through the participatory, visual research methods of the Mosaic approach (for example Clark and Moss 2001; 2005), which I have developed with Peter Moss (see Chapter 1.4). Some of the narratives are told through photographs taken by young children of both their existing and newly built learning spaces. Thus this book encompasses both visual and verbal methods of communicating in order to further our understanding of young children’s ‘ways of seeing’. John Berger (1972) made this phrase common currency in the visual arts field through the book and television series of the same name. His opening sentence explains: ‘Seeing comes before words. The child looks and recognizes before it can speak’ (1972: 7). Berger explains how photography has contributed new ways of seeing:

It is this ‘infinity of other possible sights’ which I am attempt to explore in relation to young children’s perspectives of their early childhood environments. Berger encourages us to think about seeing as more than the mechanical act of viewing an image:

This broad understanding of seeing acknowledges that interpretation is part of the process. This theme of interpretation runs through each of the chapters of this book. Acknowledging the place of interpretation is a recognition of the practice and a necessity of subjectivity. We observe from a variety of professional and personal positions, carrying a series of frames under our arms.

Journeying

Oliver Sacks refers to a description by the philosopher Wittgenstein of ‘thoughtscapes’, which Wittgenstein created with words and images:

My account which follows focuses on a three-year research study which began by aiming to assemble sketches of landscapes, including the individual and shared landscapes of early childhood environments which are in the process of change (see Epilogue for further reflection). The views and experiences of young children are central to this account. However, these landscapes are examined alongside the perspectives of other stakeholders, including practitioners and parents, together with accounts by architects. As researcher, I draw these together. These landscapes have been built up over the course of the research process, moving between, as Sacks describes narrative and reflection, images and metaphors.

The metaphor of research as a journey may particularly apply in the case of a longitudinal study. This has given the opportunity for theoretical and methodological journeying over many months. The subject matter which demanded travelling over a wide field of thought, as Wittgenstein describes, led to some surprising new meeting points, as described in Part IV. This thinking benefited from the several years of research and reflection which had taken place since the original study to develop the Mosaic approach began in January 1999. The travelling has been theoretical, practical and professional. Some of the theoretical explorations are described in the rest of this chapter. The practical element of the travelling has been as a result of the desire to contribute to cross-national exchange and dialogue about young children’s involvement in the design process. Examples gained from visits to early childhood practitioners, academics, architects and children in Italy, Norway and Iceland have particularly enriched this journey. The cross-professional dimension to this travel has benefited from meetings and workshops with architects and artists who have in turn introduced new languages for thinking about spaces and communication.

Key themes

Three overarching themes are discussed below: participation, env...