1

Great Britain’s legacy in the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf is a remote body of water whose importance to Western powers over the centuries has vastly exceeded its size. An appendage of the Arabian Sea and the Indian Ocean, it stretches 600 miles in a northwesterly direction, from its mouth at the Strait of Hormuz to its headwaters at the Shatt al Arab, the river that separates Iran and Iraq. This Gulf separates two noble societies. To the south, on the Arabian Peninsula, live the Arabs. This is the holy land of Islam, the place in which the Prophet Muhammed in the 7th century ce received the revealed word of God, and from which – in an amazing display of faith and fury – his followers set out to conquer and convert what remained of the Roman and Persian empires. To the north live the Iranians, also Muslims, but of a different stock. Speaking an Indo-European rather than a Semitic tongue, the Iranians claim a proud Persian heritage that stretches back over two millennia to Kings Cyrus, Darius, and Xerxes. Although thought by some to be the Biblical Garden of Eden, today the Arab and Persian lands surrounding the Gulf are dusty, hot, and humid. Arable land is scarce. Salt flats and barren plains stretch for miles along the southern shore; forbidding mountains arise from the northern coast. The Arabs have been cheated of deep, navigable water on their side of the Gulf; the flatlands ashore stretch underwater for miles, providing a dearth of natural ports. Iranian sailors have fared somewhat better; the natural deepwater channel through the Gulf hugs their northern shore, for example, but they too lack abundant havens from the sea, and hundreds of miles pass between good ports. Despite this paucity of harbors, however, the Gulf region sits athwart the trade and communication routes that bind Europe, Africa, and Asia. For centuries this strategic location, coupled the past 100 years with the discovery of oil, has made the Gulf a possession over which Western nations tangled. The Europeans arrived over five centuries ago, however, not to capture oil, nor to conquer, but rather to guard and to police. And though others preceded them, it would be the British who would stay for years, profoundly shaping the Persian Gulf region, and using surprisingly little force to impose their will.

The first Europeans enter the Gulf

Europeans had known for centuries of the exotic lands and riches to the east. As that continent’s residents awoke from the darkness of the Middle Ages, increasingly affluent buyers sought China’s and India’s fine silks, bright fabrics, enchanting jewels, and zesty spices. Portugal proved the first of several western nations that would dominate the Persian Gulf region. When Vasco da Gama rounded Africa’s Cape of Good Hope and continued onward to India in 1498, he opened for Portugal a century and a half during which the tiny state played an imposing role in Asia and the Persian Gulf.1

In the century that followed, the Portuguese used their European technology and military might to dominate the Indian Ocean and Persian Gulf region. Throughout the sixteenth century the Portuguese set up trading posts and fortifications in the Persian Gulf region, stretching from the Yemeni coast, northward to Muscat, thence along the Gulf coast in what is now the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and Iran. They imposed direct rule in parts of the region.2

As the larger Atlantic powers discovered the sea, however, Lisbon’s power

and influence in Asia came under attack. The English challenged the Portuguese, and in concert with Persian allies, drove them in the first half of the 1600s from their stronghold at Hormuz. As Portuguese power waned, the commercial activities of the English, Dutch, and French increased.

Britain prevails over European rivals in India. From the early seventeenth century European companies, tied closely to their home states, battled for primacy on the Indian subcontinent. In the 1600s the English, French, Dutch, Danes, and Swedes all had companies trading there.3 The scope of operations of these companies exceeded what one might expect multinational corporations to engage in today, and sometimes took on roles akin to sovereign states. They engaged in acts of diplomacy, and pursued exclusive economic treaties and political relationships with south Asia’s rulers. They often hired and managed their own military forces, officered normally by Europeans but staffed by local hires. When necessary, the companies engaged in military action against Asian leaders or their European competitors. The companies’ leaders ultimately received direction from shareholders as well as government officials back in Europe; the governance of these large trading companies became intertwined with the policies of the home state. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the British gradually gained a paramount position in India.4 Maintaining their supremacy there ultimately provided the philosophic rationale for the nation’s entry into the Persian Gulf.

Britain secures approaches to India. Like the Portuguese who fortified the seaborne route to India, the British found themselves concerned with protecting the strategic flanks to their lucrative Indian colony. Commencing in the late 1700s the British took control of critical chokepoints leading to the Indian Ocean. In the 1790s, for example, they snatched from the Dutch the seaborne entryway from the Atlantic, South Africa’s Cape Colony. Shortly thereafter they took the distant Pacific gate to India, Malacca, and several decades later established a colony and military garrison at Singapore. The possession of these distant chokepoints allowed Britain to prevent rivals from threatening India from the sea, while at the same time allowing London to influence and control travel and trade between the continents.

At about the same time, political events in Europe prompted the British to look toward the Persian Gulf region. Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt in 1798 gave rise to fears in London that the French might move into the weak states of the Gulf region and, using the Persian Gulf and Red Sea routes, threaten India. The Arab lands bordering on the Persian Gulf, as well as Persia and Afghanistan began to loom large in British minds.

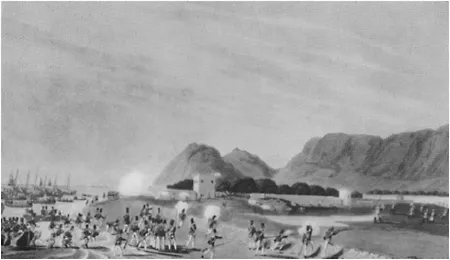

The Persian Gulf in the early 1800s proved a place of disorder. Arab and Persian notables there fought for primacy. On the eastern side, Qajar dynasty leaders proved weak, like their Arab neighbors across the Gulf. Wahhabi puritan zealots burst forth from their Arabian desert strongholds in what is now Saudi Arabia. Fighting spilled over into maritime attacks on shipping from India, and also disrupted the lucrative pearling season. Seaborne brigands exploited the lack of central authority in the region, and worked from the shallow waters of the southern Gulf, leading the British later to refer to the region as the “Pirate Coast.”5

Into these troubled waters in the early 1800s sailed the ships of the Royal Navy and the British-run Indian Navy, ushering in a period of over a century and a half in which British rulers used a modest amount of military force – primarily naval – to suppress piracy and the slave trade, and to promote peace amongst the Gulf’s warring factions, while at the same time keeping at bay Britain’s Great Power foes who cast covetous eyes toward India.

The British maintain order with a small military and diplomatic force

With colonial interests and demands all over the world, the British for most of the nineteenth century deployed to the Persian Gulf region only a handful of naval ships.6 Working hand-in-hand with a cadre of British diplomats representing the Indian Government, however, this combination proved able to suppress piracy and to enforce truces between the warring parties of the Arabian coast. How did they do it? With a mixture of good intelligence collection, skilled negotiations, credible naval deterrence, and gunboat diplomacy. When confronted by Great Power foes, furthermore, British leaders did not hesitate to employ the British Indian Army. Behind London’s success

in maintaining order in the Persian Gulf region, then, ultimately stood the forces of the Indian subcontinent.

Accounts of some early nineteenth century British naval journeys in the Persian Gulf illuminate roles the British military forces fulfilled. One account, for example, describes the value of the intelligence that naval forces collected, details how the British negotiated, and shows how little the British really coveted the region for its own sake. In an 1831 letter to a naval leader at sea, the British Resident in Bushire writes:

In most cases the British achieved their political goals with the simple presence of a man-o-war, although when that failed their naval crews occasionally applied more extreme forms of coercion. The port blockade served as one option, for example, which British crews could impose by force, using “such exertions … in enforcing it as you may deem practicable.”8 In other situations, when a local Arab had plundered a British commercial vessel, for example, the Resident directed the naval leaders to go ashore to apprehend the guilty party, or demand from the appropriate tribal leader a monetary sum.9

Should a foe ashore still not submit to Britain’s will, however, the naval vessels might open fire. One 1820 letter discussed the optimal weapons for retaliating against a wayward Arab ashore who had offended the Crown, including “cruizers” with 10-pound long guns, “luggage boats to be fitted with gun and mortar boats,” and 8 inch “howitzers.”10 At every step the British made a conscious effort to convince the Gulf locals that further reinforcement lay just over the horizon, and that any attempt to resist the will of the Crown would ultimately lead to their own destruction. Capturing the essence of this philosophy, the British Resident in 1832 makes clear that an offending Arab must be made to understand that “strong measures are sure to follow and that there is no release except in ultimate submission.”11

The naval forces plying the Persian Gulf waters in the 1800s and early 1900s, of course, did not possess unlimited authority, and they operated with

guidance from British leaders in India and London. Overall strategic naval policy for the Persian Gulf emerged from a dialog between the Government of India, the Foreign Office, and the Admiralty. The Commander in Chief of the East Indies Station, in turn, controlled naval affairs over a vast expanse that stretched from the Red Sea to China.12 Navy crews normally arrived in the Gulf with general orders from Bombay, but often accepted specific direction and tasking from the British Resident in Bushire, who provided intelligence targets, assigned ports to blockade, or identified individuals to apprehend.

The Gulf Resident in Bushire, then, played a critical role in military affairs of the Persian Gulf, and his duties proved expansive, akin in some respects to those of an ambassador.13 The Resident served as a representative in the Persian Gulf of the British Government ...