![]()

PART

I

INTRODUCTION

![]()

CHAPTER

1

The Rise and Promise of Applied Psychology in the 21st Century

Stewart I. Donaldson Dale E. Berger

Claremont Graduate University

Profound changes are occurring throughout the world in the new age of rapidly advancing information technology and globalization. The need for theory and research-based applications of the social sciences has never been greater, and is likely to grow even stronger as the 21st century unfolds. At least on the surface, applications of the social science discipline of psychology seem to be far outpacing other social sciences in terms of growth and impact on human welfare and social betterment. This volume will take you beneath the surface to discover important ways that psychology is growing as it continues to mature as a discipline and profession.

PSYCHOLOGY COMES OF AGE

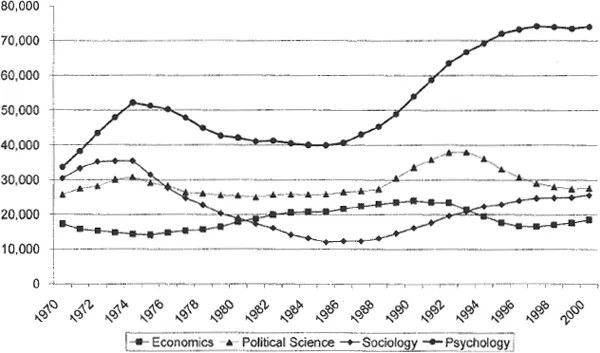

Psychology has been extraordinarily successful at attracting the next generation of social scientists into the discipline. The growth of interest in psychology during the past three decades is most striking when we compare psychology to our sister social science disciplines of sociology, political science, and economics. Figure 1.1 shows the number of bachelor's degrees granted by year from 1970 to 2000 by discipline. Although there were fluctuations over this 30-year period, in 2000 psychology's sister disciplines conferred about the same number of bachelor's degrees as they did in 1970.

The growth in psychology as an undergraduate major is striking. In sharp contrast to the other social science disciplines, the number of bachelor's degrees conferred in psychology more than doubled, from 33,679 in 1970 to 74,060 in 2000 (U.S. Department of Education, 2005). Furthermore, the most recent data available show there were 76,671 bachelor's degrees awarded in psychology in 2002, the most ever, while the sister disciplines remained stable. This growth represents a remarkable achievement for the discipline of psychology, and it presents the discipline with an imposing opportunity. Each year in the past decade has produced 70,000 or more new college graduates with psychology degrees in the United States alone.

FIG. 1.1. Bachelor's degrees by year by discipline (USA).

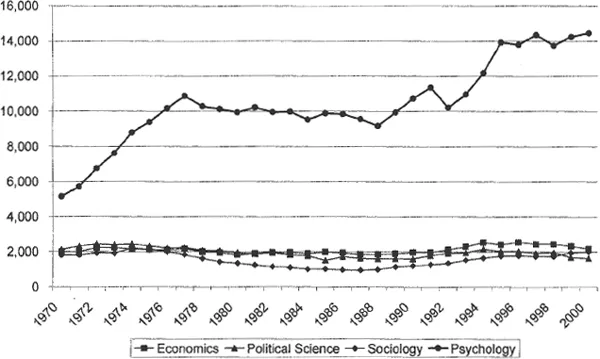

The success of psychology is even more remarkable when we consider graduate training. Again, our sister disciplines have no more than held their own over the past 30 years, with only modest fluctuations. In sharp contrast, Fig. 1.2 shows that the number of master's degrees each year in psychology has nearly tripled, rising from 5,158 in 1970 to 14,465 in 2000. In 2002, this number rose to 14,888 (U.S. Department of Education, 2005).

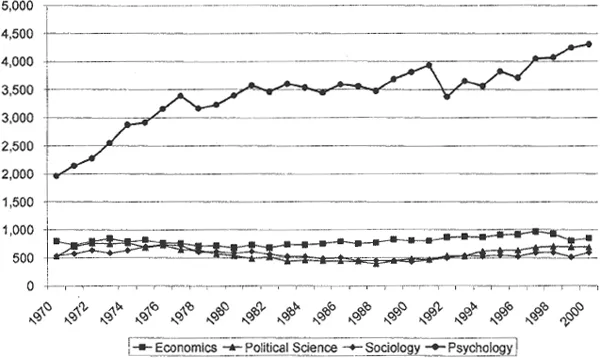

A similar pattern is seen in Fig. 1.3, which shows the number of doctorates granted per year (U.S. Department of Education, 2005). While our sister disciplines have not grown over the past 30 years, psychology has more than doubled the number of people entering the profession at the doctorate level each year. In recent years, more than 4,000 people earned doctoral degrees in psychology each year.

EMPLOYMENT TRENDS

Where do all these new psychology graduates find employment? Is the old stereotype true, that education in psychology is not practical, and typically leads to low-paying jobs and career paths? Does a degree in psychology limit you to working in traditional counseling and mental health care service jobs and settings? Do PhD-level psychologists trained in the research areas only teach, write, and conduct research? The chapters in this volume provide compelling evidence that these old stereotypes of psychology are outdated and highly inaccurate. You will read about numerous ways that psychology majors now apply their education.

FIG. 1.2. Master's degrees by year by discipline (USA).

FIG. 1.3. PhD degrees by year by discipline (USA).

One special focus of this volume is identifying and describing personally rewarding and lucrative career opportunities that involve applying the science of psychology. Approximately 60,000 new psychology graduates, or about 80% of those who earn bachelor's degrees in psychology in the United States, enter the workforce each year (Fennell, 2002). Only 25% of these new graduates report that they are working in psychology or a closely related field. This fact suggests that every year approximately 45,000 new psychology graduates apply their education and skills across a wide range of occupational settings outside of jobs traditionally associated with psychology:

• 41% in for-profit organizations

• 18% in federal government

• 11% in nonprofit organizations

• 10% in state and local government

• 7% in universities

• 13% in other educational organizations (Fennell, 2002).

There is also a trend toward more diverse careers applying the science of psychology at the graduate level. Although it remains true that the majority (60%) of PhD-level psychologists are trained and work in the traditional mental health service areas of clinical, counseling, and school psychology, many more of the other 40% who are trained in the research areas (e.g., social, personality, developmental, organizational) choose careers in applied settings rather than university faculty positions (Fennell, 2002). For example, in 1970 only 30% or approximately 600 new PhD-level research psychologists reported working outside the university in applied positions. By 2000, these numbers swelled to more than 2,100 as approximately 50% of new PhDs in research psychology obtained applied positions over faculty positions.

In summary, as psychology has blossomed as a discipline and profession over the past three decades, far outpacing our closest sister disciplines, students trained in psychology have found opportunities to apply their skills in many new ways toward the betterment of society and human welfare. Opportunities for students entering the field of psychology have never been greater than today.

APPLIED PSYCHOLOGY

It is clear that the field of psychology has grown and changed markedly over the past generation. The field is now in the position of enjoying a powerful flow of undergraduates who are eager to develop careers where they can use their training and follow their interests in psychology. The extraordinary growth of applied psychology, especially in applied areas of business, government, law, health, prevention, social change, and education, signals a momentous change in the role of psychology in society. The most prominent professional associations of psychologists have taken note of this change, and now commit significant time and resources to further the development of applied psychology.

The oldest international association of psychologists, the International Association of Applied Psychology (IAAP) continues to grow and now boasts more than 1,500 members from more than 80 countries. IAAP continues to be a global leader in sponsoring events and activities to fulfill its mission of promoting the science and practice of applied psychology, and facilitating interaction and communication about applied psychology around the world (see http://www.iaapsy.org). Additionally, the largest American psychological professional organizations have developed key initiatives aimed at elevating the profile and impact of scientific psychology in society. For example, the Human Capital Initiative and the Decade of Behavior are two notable initiatives that illustrate this new energy and value that has been placed on applying psychology to promote human welfare and achievement in society (American Psychological Association, 2005c; American Psychological Society, 2004).

In 1990 the American Psychological Society (APS) convened a Behavioral Science Summit with representatives from 65 psychological science associations, a group that eventually grew to include more than 100 organizations. These organizations unanimously endorsed the development of a national research agenda that would help policymakers set funding priorities for psychology and related sciences. The result was ‘The Human Capital Initiative,’ which outlined six areas of broad concern where psychological science could make substantial contributions:

• Productivity in the work place

• Schooling and literacy

• The aging society

• Drug and alcohol abuse

• Health

• Violence

Each of these areas presents issues that are fundamentally problems of human behavior. The Human Capital Initiative embraced the goal of coordinating efforts to apply social science to address these fundamental problems that transcend boundaries. A premise is that to achieve the goal of maximizing human potential, we need to know in scientific terms how people interact with their environment and each other–how we learn, remember, and express ourselves as individuals and in groups–and we need to know and understand the factors that influence and modify these behaviors. This effort has motivated an agenda for basic research and funding policies, and it has supported applications of psychological science outside of the university.

More recen...