![]()

Part I

![]()

1

What is dramatherapy?

Drama is mimetic action, action in imitation or representation of human behaviour.

Esslin, An Anatomy of Drama

Introduction

There are two perceptions at the heart of this book. The first is that drama and theatre are ways of actively participating in the world and are not merely an imitation of it. The second is that within drama there is a powerful potential for healing.

The term ‘dramatherapy’ refers to drama as a form of therapy. During the twentieth century developments in a number of different fields such as experimental theatre and psychology have resulted in new insights into the ways in which drama and theatre can be effective in bringing about change in people: emotional, psychological, political and spiritual change.

This book will offer definitions and examples of what dramatherapy is and research into what it offers clients. It will draw on different sources from theory and professional practice all over the world: from England to Taiwan, from Canada to Sri Lanka. Theoretical definitions and those arrived at by professional associations and health care providers offer one kind of answer to ‘What is dramatherapy?’ but the following moments from vignettes contained in the research undertaken for the second edition of this book draw us straight into the heart of the question, by taking us to where the meaning of dramatherapy matters most: within work with clients. In this place, adolescents tell each other for the first time that they are HIV positive, a woman walks through a landscape that holds her life, cloths create the experience of tsunami waves that destroy homes and families, helmets shut out the world and a child creates a head that represents the man who shot his brother.

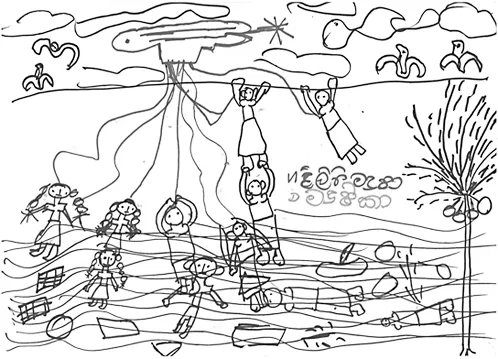

Child survivors of a tsunami in Sri Lanka

I had placed a blue cloth in the centre and waited to see what would emerge. The children began to move their arms up and down and we all began to sway spontaneously. The energy began to build and a section of the circle lunged into the centre and then another section. There was a lot of laughter, the lunging became more intense and I requested that the translator ask, ‘What is the sound to this movement?’ Then it came: ‘Whoosh!’ Others joined in. We were running in and out of the circle, hands linked: ‘Whoosh!’ The energy and the noise built further, bouncing off the temple walls, a sort of contained chaos. ‘What’s happening?’ I shouted above the din. They told my translator, ‘It’s tsunami! Tsunami coming!’

(Debra Colkett, Chapter 7, p. 157)

A woman in a group for older people who hear voices in England

Jilly chose a roaring lion and placed it among all the other animals, where it could see everyone else and was ready to pounce. After a while she laid a lamb at its feet. She spoke about the symbolism. She spoke about her voices as being like the anger of the lion which smothers her. She told the group that her voices constantly swear at her and tell her she is responsible for all the world’s disasters. She said she identified with the lamb.

She said she felt very vulnerable and as if her life had been sacrificed to her voices. She was also able to make a connection with her own anger which she had split off and was perhaps placed in the voices/lion.

(Jo Van Den Bosch, Chapter 6, p. 148)

A group for adolescents with HIV in South Africa

It was very quick role play. Both were sitting on chairs. Nomsa turned to Miriam.

Nomsa: Can I trust you?

Miriam: Yes.

Nomsa: I am HIV positive.

Miriam: [Giggles with hand over her mouth]

Nomsa: Did you hear me?

Miriam: Yes.

Nomsa: Well?

Miriam: Just don’t tell anybody else.

(Kirsten Meyer, Chapter 5, p. 97)

A teenager in a school for pupils with emotional and behavioural difficulties in England

A boy of 13, Peter, stands under a spotlight. He is dressed in a cloak and is covered by a mask in the form of a shiny, totally black helmet, twice the height of his head. In appearance it is not unlike those worn by medieval jousting knights. The previous week he had spent over 30 minutes colouring the helmet’s card in several layers of vigorously applied black wax crayon. No part of his face is visible. There is only a small slit for an eyehole. A flap is hinged over the hole, and this is attached to a string which the boy can pull down to cover his eyes completely. As he turns round slowly to the group, he says, voice muffled, ‘No one can be seen unless they kneel down first in front of me.’

(Phil Jones, Chapter 6, p. 140)

A woman in individual therapy in England

The landscape came from a poem which Kia brought to therapy. She explored the feelings it engendered in her, we explored those feelings of despair, death, foolishness and failure and also explored the contrasting feelings of hope, life, laughter and trying. From this engagement Kia spent the next few sessions creating a huge painted and collaged landscape, which I witnessed. As the landscape took shape I encouraged her to tell me its story. It was split into two definite sides. On one side there was a huge slate cliff with barren trees and a dark and dangerous cave which often flooded. This place held memories of pain and tension and a large and powerful waterfall separated it from a more gentle and containing landscape. On this side the water followed more gently and within the hills there were caves to keep her character (which we had yet to meet) safe and dry. These caves also kept the character hidden as he or she did not like to be seen by people.

(Sarah Mann-Shaw, Chapter 10, p. 261)

A child from Sierra Leone

The next session Abui wanted to make a mask. He cut out a large head, stuck on wild hair and called it ‘evil’. He talked quite a lot this session, decorating the mask, then trying it on himself, as if freed from the fear that this evil could harm him now.

Abui spoke of a man with powers to do harm to people in the villages, the man people feared most back home. Using the name of ‘holy spirit’ or ‘The Dr’. The man who decided who would die and left people to burn on rubber tyres. This was the man who shot his brother in front of the whole family. I was a witness to part of the horror Abui had experienced. How could I reflect back to him anything that didn’t overwhelm us both with the enormity of what he was telling me?

(Roya Dooman, Chapter 5, p. 127)

These moments from clinical work occur continents apart, with clients at the beginnings and ends of their lives. Therapists, within the research which this book draws on, provided vignettes from their practice that were followed up by analysis of the ways in which they saw the core processes at work in the therapy. As later chapters reveal, their contexts could not be more different: from dramatherapy taking place in a temple within the ruins of a tsunami-devastated village to a large National Health Service run mental health hospital in the UK, from a small school in a deprived area of a major city to a refuge for women in Sri Lanka. What unites all of these is the way drama becomes a vital part of clients encountering their lives, transforming their experience of themselves and the way they participate in the world they live in. This book and its research into the core processes at work within dramatherapy will show ways of understanding and describing why and how drama can be allied to therapy in a way of working which is as powerful as these moments illustrate.

Drama as necessary to living

In the past one hundred years the theme of drama and theatre as ‘necessary’ to healthy societies and healthy individuals has re-emerged. Evreinov says that theatre is ‘infinitely wider than the stage’ and not just for entertainment or instruction; it is ‘something as essentially necessary to man as air, food and sexual intercourse’ (1927:6). This phrase is echoed across the century. Forty years later, Peter Brook seeks a theatre that is as ‘necessary as eating or sex’ in The Empty Space (1968). Schechner says of the special world created in performance, ‘no society, no individual can do without it’ (1988:11). But why should theatre be so essential? How can theatre be necessary?

The general theme is not a new one. However, many societies in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries have understood its implications in particular ways. This understanding considers that participating in drama and theatre allows connections to unconscious and emotional processes to be made. Participation is seen to satisfy human needs to play and to create. The festive act of people coming together through drama and theatre is seen to have social and psychological importance. Theatre is both an activity set apart from everyday reality, while at the same time having a vital function in reflecting upon and reacting to that reality.

A theatre has been sought by practitioners such as Grotowski, Brook and Boal which can bring people together and can comment upon and deeply affect their feelings, their politics and their ways of living. I consider that dramatherapy originates from these beliefs, which see theatre as being necessary to living. This book will explore one particular way in which drama and theatre processes are essential, a part of the maintenance of well-being or a return to health.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, drama was used as a recreation, as an adjunct to the main therapeutic ways of working with people in care or health settings. The key aspects of the therapy remained outside the clients’ experience of drama. Drama was seen only as a way of making stays in hospital more enjoyable, or sometimes as an opportunity to raise emotional material which would be dealt with later in the hands of the psychologist or psychiatrist.

Over the past four decades a change has come to be fully acknowledged: that the drama itself can be the therapy. This change marks the emergence of dramatherapy as it is currently practised. There are two main aspects to this change or development. One is that the dramatherapy session can de...