1 ESTABLISHING THE PARADIGMATIC MUSEUM

Georges Cuvier’s Cabinet d’anatomie comparée in Paris

Philippe Taquet

Georges Cuvier was born on the 23 August 1769 to a modest middle class family in the city of Montbéliard in the east of France. The status of this Lutheran city, at that time attached to the duchy of Wurtemberg, gave Cuvier the opportunity to acquire an excellent education at the Caroline University. In 1788, newly appointed as a tutor in Normandy, Cuvier devoted his free time to his passion for natural history. While the rest of France was in revolution, Cuvier collected plants and insects and dissected fishes, birds and marine organisms (Taquet 2006).

An avid reader of the works of Aristotle, Cuvier soon began to elaborate a new plan for a general natural history: ‘searching for the relationships between all living animals with Nature’. His inspirations were many: he became an admirer of the Swedish taxonomist Carolus Linnaeus and his methods of classification; he discovered German Gottlieb Conrad Storr’s essay on mammal classification; he was impressed by the German naturalist Karl Friedrich Kielmeyer; he gained an understanding of the scope of comparative anatomy from the works of the French savant Louis Jean Marie Daubenton; he consumed enthusiastically the works of Antoine Laurent Lavoisier, who proposed a new approach to chemistry, and Antoine Laurent de Jussieu, whose new natural method for classifying plants suggested correlations between the different parts of the organism. Cuvier felt, for example, that by applying Jussieu’s botanical approaches he could transform zoology from a science of memory and nomenclature into something new, within which could be located combinations and affinities like those seen in chemistry and the problem solving utilised in geometry.

Cuvier understood that the realisation of this grand project required the acknowledgement of the scientific community, particularly those Parisian naturalists working at the Cabinet d’histoire naturelle in the Jardin du Roi, an institution which became known, in 1793, as the Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle. Understanding that the museum’s treasure house of zoological specimens was key to his plans, Cuvier sent manuscripts of his work to the entomologist Guillaume Antoine Olivier and the zoologists Bernard Germain Etienne de Lacepède and Etienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire. These demonstrated his capabilities in natural history and his talents as observer and artist. The museum was then recovering from the disorder of The Terror and saw in Cuvier a young naturalist free from any links with the old regime; a follower of Linné rather than Buffon. As a consequence of these fortuitous circumstances and being an already prodigious talent, Cuvier – then only 26 years old – became engaged at the museum in July 1795 as assistant to Jean Claude Mertrud, who held the chair of animal anatomy. Almost immediately, he began work on his ‘Tableau élémentaire de l’Histoire naturelle des animaux’, which was to take on material form in a new Cabinet d’anatomie, supported by a team of efficient preparators and assistants.

Cuvier’s Cabinet d’anatomie

Noting the relationship to Lavoisier’s science, Cuvier defined his programme as follows:

Chemistry exposes the laws according to which elementary molecules of substances act one upon the other at short distances . . . The natural history of any organisms, to be perfect, must include,

- a) The description of all sensible properties of this organism, and of all its parts

- b) The relationships of all these parts between themselves, the movements which are in action, and the modifications they are submitted to during their union

- c) The active and passive relationships of this organism with all other organisms of the Universe

- d) And finally the explanation of all these phenomena

Natural history considers from only one point of view all natural living beings and the common result of all their actions in the great overall picture of Nature. Natural History determines the laws of coexistence of their properties . . . It establishes the degrees of similarity which exist between the different organisms, and the groups according to degrees. Natural History can only reach its perfection when completed by the specific history of all natural living beings.

(Cuvier 1797)

On arriving at the museum, Cuvier made an inventory of the comparative anatomy collection, which had been assembled as a direct result of the works of Buffon.

The Great man had conceived a plan for the history of animals, more ambitious than his predecessors; he wanted the whole organization to be known, and it is possible to say that, with the help of Daubenton, he started to realize this project, in a correct way, for the viviparous quadrupedal animals.

Daubenton, who was in charge of the dissections, worked to preserve as much as possible of parts of the animals, in alcohol or dried. Of these the skeletons, which were described and figured in the main edition of the Histoire Naturelle, had been kept.

However, Buffon abandoned this part of his plan in his Histoire Naturelle des Oiseaux and in the supplements of the Histoire des Animaux Quadrupèdes. There was no part devoted to anatomy and the collection did not increase. Instead, the quadruped skeletons were put into storage in order to make space for more spectacular artefacts which were then being added to all parts of the Cabinet. As a consequence the skeletons suffered considerable damage. The situation stayed like this for many years.

(Cuvier 1803)

Cuvier’s rise in Paris was meteoric, with Cuvier eventually taking over Mertrud’s chair of animal anatomy in 1802, and in so doing gaining control of the anatomy collections: ‘So it is from that time that I really began the collection in the Jardin du Roi’ (Cuvier 1822). He noted at the time that: ‘It was lacking a room for the exhibition. The soft preparations were arranged in the Cabinet with the complete skeletons. The skeletons were partly in the basement, partly in the attic, and nobody knew where to put the new preparations’ (Cuvier 1803). Later, Cuvier remembered:

The Garden had just acquired large buildings occupied by storehouses which had formerly been used for the management of cabs and which were just against the house were I was living. I managed to make a hole in the wall. I ordered three or four skeletons that Mertrud had prepared to be moved from the attic into the new space. I also collected . . . what was left from the old skeletons prepared by Daubenton for Buffon, which were piled up like faggots. And it was while completing this enterprise, sometimes helped by professors of the Museum, annoyed sometimes by others, that I succeeded in increasing my collection so much that nobody was opposed to its enlargement.

(Cuvier 1822)

To manage his enterprise successfully, Cuvier surrounded himself with efficient and devoted collaborators:

there was no assistant anatomist for the manual tasks as there was for the other collections, but the zeal of the citizen Rousseau supplied the lack of help [Pierre Rousseau, 1756–1829, followed by his son Emmanuel Rousseau, 1788–1868]. In spite of the modest salary it was possible to give to him, pushed by the love of anatomy, he worked very hard to increase the treasure, modest at the beginning, which was trusted to him.

(Cuvier 1803)

Cuvier called for his relations from Montbéliard to help him in Paris: his brother Frédéric (1773–1838), who became professor and first keeper of the chair of comparative physiology of the museum; his cousin Georges Duvernoy (1777–1855), who worked by Cuvier’s side from 1802 to 1805; Charles Léopold Laurillard (1783–1853), who was placed in charge of the anatomical drawings from 1804; and Constant Duméril (1774–1860), who helped with the writing the of first two volumes of the Leçons d’Anatomie Comparée, a role later taken on by Georges Duvernoy for the final three volumes.

Cuvier later called upon his daughter-in-law Sophie Duvaucel and his daughter Clémentine, who were both put in charge of drawing fishes. His wife was also called upon; she made the catalogue of the preparations given to the Royal College of Surgeons in London. Cuvier would also later surround himself with foreign collaborators: Miss Sarah Lee, the widow of the explorer Thomas Bowdich, and Joseph Barclay Pentland, an Irish naturalist who worked with Cuvier for many years before becoming a diplomat of the British Foreign Office in Bolivia.

Despite all the help he would receive there was little hint initially of the grandeur of the project. As one of his helpers later recalled: ‘often at the beginning, he and his brother were obliged to saw and fix the almost unpolished boards themselves, onto which the skeletons were then placed in order’ (Laurillard 1836). His collecting had begun with the dead animals of the menagerie, as well as those given or sent by private individuals, those bought specially from the market or elsewhere, and those in the zoological collections that were unused (Cuvier 1803). He had the building, which was composed of two huge rooms, divided into several smaller rooms. Embryonic British geologist Charles Lyell reflected on the spatial arrangement when he spent two months in Paris in 1823. Clearly, the ordering and control of people, space, books and objects was fundamental to Cuvier’s way of working:

I got into Cuvier’s sanctum sanctorum yesterday, and it is truly characteristic of the man. In every part it displays that extraordinary power of methodising which is the grand secret of the prodigious feats which he performs annually without appearing to give himself the least trouble. But before I introduce you to this study, I should tell you that there is first the museum of natural history opposite his house, and admirably arranged by himself, then the anatomy museum connected with his dwelling. In the latter is a library disposed in a suite of rooms, each containing works on one subject. There is one where there are all the works on ornithology, in another room all on ichthyology, in another osteology, in another law books, etc. etc. When he is engaged in such works as require continual reference to a variety of authors, he has a stove shifted into one of these rooms, in which everything on that subject is systematically arranged, so that in the same work he often makes the round of many apartments. But the ordinary studio contains no bookshelves. It is a longish room, comfortably furnished, lighted from above, and furnished with eleven desks to stand to, and two low tables, like a public office for so many clerks. But all is for one man, who multiplies himself as author, and admitting no one into this room, moves as he finds necessary, or as fancy inclines him, from one occupation to another. Each desk is furnished with a complete establishment of inkstand, pens, etc., pins to pin Manuscripts together, the works immediately in reading and the Manuscript in hand, and on shelves behind all the Manuscripts of the same work. There is a separate bell to several desks. The low tables are to sit at when he is tired. The collaborators are not numerous, but always chosen well. They save him every mechanical labour, find references, etc., are rarely admitted to the study, receive orders, and speak not.

(Lyell 1888)

Anatomy of the Cabinet

In 1802, Cuvier gave an inventory of the skeletons and preparations that could be seen in the new Cabinet d’anatomie comparée (Figure 1.1). Of the 2,898 preparations, 526 were complete skeletons, of which 102 were old preparations. These formed nearly half of the 1,239 osteological specimens. In addition, there were 1,136 soft preparations preserved in alcohol and a further 523 preparations of invertebrates.

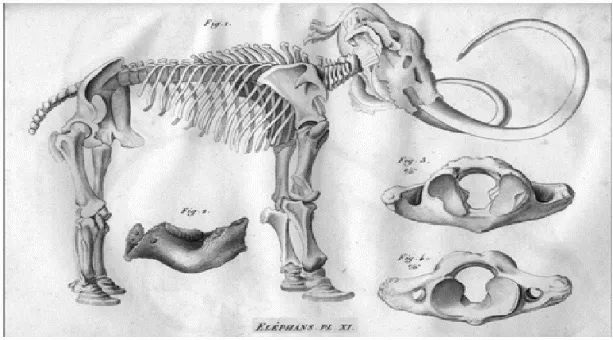

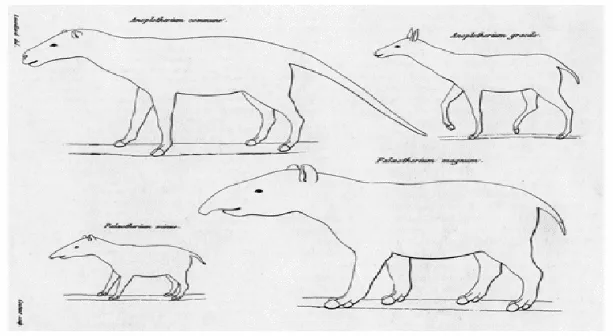

An inventory made by Joseph Barclay Pentland and Achille Valenciennes on Cuvier’s death, in 1832, reveals that the collection continued to grow prodigiously. By then it contained 16,665 preparations (Valenciennes, Laurillard and Pentland 1833). This included, among other things: 2,625 complete skeletons, 2,150 skulls and 1,389 disarticulated heads (Figure 1.2). It also held 56 human skeletons from all parts of the world: Papous from New Guinea, Aborigines from Australia, Indians from Canada, Patagons and Araucans from South America, two Bushmen, two Guanches from Tenerife, one Dutchman, one Flemish, 25 French, one Italian and one English. There was also the skeleton of Soleyman el Haleby, who assassinated the famed General Kléber in Cairo in 1800. It had been brought back by Napoleon’s surgeon, Baron Larrey. Among the collection of apes were two orangutans (though, of course, no gorilla, which was not described until 1847). The collection also contained eight complete skeletons of cetaceans, including a cape whale and a right whale. In total, the collection held 7,626 mammal specimens, 2,310 specimens of birds, 800 skeletons of fishes and 906 arthropods. There were also fossil animals: the remains of Palaeotherium and Anoplotherium from the gypsum of Montmartre and bones of Anthracotherium, Lophiodon, mammoths, mastodons, hippopotamus and rhinoceros (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.1 The Cabinet d’anatomie comparée in the Jardin des Plantes in Paris. Behind Georges Cuvier’s house is the building that was transformed for the presentation of the com - parative anatomy collection. On the fi rst fl oor are the rooms where Cuvier worked.

Photo: the author.

Figure 1.2 Eléphans. One of the plates of the Recherches sur les Ossemens Fossiles volumes. Plate XI, T.I, 1821.

Photo: D. Geffard.

As Cuvier’s status grew he relied rather less on the animals of the local menagerie. He became connected into a network through which flowed specimens from around the world. For example, he received material from Nicolas Baudin’s expedition to Australia, and from the naturalist François Péron and illustrator Charles Alexandre Lesueur after their exhibition at La Malmaison Castle, where they were presented to Napoleon’s first wife, Josephine de Beauharnais. Pierre Antoine Delalande brought Cuvier a tapir from Brazil and, from the Cape of Good Hope, a rhinoceros, hippopotamus and two large and beautiful species of whale. His son-in-law, Alfred Duvaucel, with his friend Pierre Médard Diard, sent him an Indian rhinoceros, gibbons, a dugong and numerous species of mammals from Asia. He was offered the skeleton of the walrus collected during Captain William Edward Parry’s expedition to the Arctic. The list of naturalist travellers willing to donate to Cuvier’s project grew: Leschenault, Quoy, Gaimard, Lesson, Garnot, Reynaud, Rang, Milbert, Dussumier and so on.

Figure 1.3 Reconstitution of the animals of the gypsum of Montmartre. Plate LXVI, T.III, 1822, Ossemens Fossiles.

Photo: D. Geffard.

Cuvier took in these objects and placed them in a systematic arrangement of his own design: ‘The preparations have been made and placed in physiological arrangement. This means that they are distributed not according to the animals from which they are originated, but according to the organs from which their structure can be understood’ (Cuvier 1803). As noted by Philippe Sloan (1997), the purpose of the arrangement was not to compare organs across different subkingdoms (such as the eye of a cephalopod with that of a mammal) but rather to show that inside each class, or subkingdom, organs share relationships and functions. Cuvier’s aim was to illustrate and prove the assertions of his groundbreaking Règne Animal, which drew upon this mode of analysis to promote a natural distribution of species, genera and families inside the different classes.

It was in this book that Cuvier explained his method, its application to natural history and its utility as an introduction to comparative anatomy.

Here, I go partly climbing from the lower divisions to the upper divisions, by the way of comparison and rapprochement; in part also going down from the upper to the lower by the way of the subordination of the characters; comparing precisely the results of the two methods, verifying the one by the other, and establishing always the connection between the external and the internal forms, which all together are an integral part of the essential being of each animal.

(Cuvier 1817)

Cuvier was here probably also taking into account recent observations of Etienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, who was making links between oviparous vertebrates, through an analysis of the composition of the different skulls. However, Cuvier fundamentally disagreed with Geoffroy’s assertion that there existed a single body plan. Geoffroy was then making bold connections between the structure of the vertebrates and that of molluscs, such as the octopus. For Cuvier, the ‘embranchements’ (subkingdoms) were very distinctive entities, which could not be united together in this way.

The result of Cuvier’s huge effort to prepare, study and arrange the collection was his proud proposal, in 1812, of the different classes, to be articulated in Le Règne Animal Distribué d’Après Son Organisation, Pour Servir de Base à l’Histoire Naturelle des Animaux et d’Introduction à l’Anatomie Compare. It divided nature into four subkingdoms: vertebrata, molluscs, articulata (arthropods) and zoophytes or radiata.

As William Coleman wrote:

The Règne Animal was to be a logical and complete exposition of all known animals. It was not what is today called a taxonomic key. On the contrary, the experienced naturalist used Cuvier’s work in order to gain more profound knowledge of a specimen, or a species, or any zoological unit whose identity he already knew. Using the index or his knowledge of the plan of...