![]()

Part I

Taking a psychological approach

![]()

1

Psychological processes in engagement

Morna Gillespie and Alan Meaden

Engagement can be seen as a stand-alone intervention as well as a central vehicle for the delivery of other interventions (McCabe and Priebe, 2004; The Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health, 1998). Placing engagement in such a prominent position necessitates first establishing a clear understanding of what we mean by the term, before examining the factors that affect it and the development of tools for measuring it.

Defining engagement: Alliance, Compliance or Participation?

Any definition of engagement must address how individuals view important relationships, how open they are to treatment and how useful they consider it to be. These three concepts are often referred to as Therapeutic Alliance, Compliance (usually with medication) and Participation; all of which are used synonymously with the term ‘engagement’.

Within psychiatry, the term ‘engagement’ can mean medication compliance, attendance at appointments or a collaborative involvement in a therapeutic relationship (Catty, 2004). The latter most closely matches the concept of therapeutic alliance as defined by Bordin (1979). This theoretical perspective has the best fit with multi-disciplinary disciplinary team case management. Bordin’s pan-theoretical model has three components: Goals (agreed-upon outcomes), Tasks (mutually accepted responsibilities of client and clinician to achieve goals) and Bonds (relationships between client and clinician, including trust, acceptance and confidence). Viewing engagement in this way clearly defines it as a process concerned with the individual and how they view their relationships with clinicians and important others.

This concept alone, however, is not adequate to capture fully all the processes involved in engaging service users in Assertive Outreach Teams. Catty (2004) notes the complexity of applying the construct of therapeutic alliance in a context where increased contact may not equate with a stronger alliance. In such circumstances the opposite may be true and service users may feel intruded upon by repeated attempts to make contact with them, weakening therapeutic alliance. Subsequent poor engagement may lead clinicians to increase their efforts to make contact, thus compromising therapeutic alliance still further. In order to be meaningful in assertive outreach settings, the concept of engagement may therefore need to be more broadly defined in order to encompass how the process relates to the service, its goals and ways of working.

The term ‘compliance’ has often been taken to mean engagement and is a well-established term within the treatment literature. May (1974) first described it as ‘the extent to which a person’s behaviour (in terms of taking medications, following diets, or executing lifestyle changes) coincides with medical or health advice’ (as reported by Haynes (1979); cited in Blackwell, 1997:5). McPhillips and Sensky (1998) perceive compliance to be the passive acceptance of clinician advice by the client, while adherence is characterised by clients having a more active, collaborative role. Although adherence through collaboration is more desirable, they acknowledge that to some extent compliance cannot be completely abandoned when working with clients with severe and enduring mental illness. Such approaches may be seen as closely allied with the supportive psychotherapy tradition with expected and prescribed roles for patient and clinician (Parsons, 1951).

Interestingly, Compliance Therapy (Kemp, Kirov, Everitt, Hayward and David, 1998) itself encourages a collaborative weighing up of the costs and benefits of taking medication and is only likely to be effective if the person themselves has a free and informed choice or is motivated to take their medication. Compliance can be seen as paternalistic and undermining of empowerment whilst informed choice embodies active participation (Fisher, 1997). A service where the emphasis is too focused upon compliance may create an imbalance in the power relationship between client and clinician, encouraging overly active, even aggressive interventions, coupled with passive, submissive responses. Undoubtedly, however, the concept remains of importance to clinicians, and indeed policy makers, and features in many current measures of engagement as one or more items. We may usefully consider compliance as a core feature of engagement, reflecting service goals, but one that should be embedded within a broader collaborative process that promotes choice.

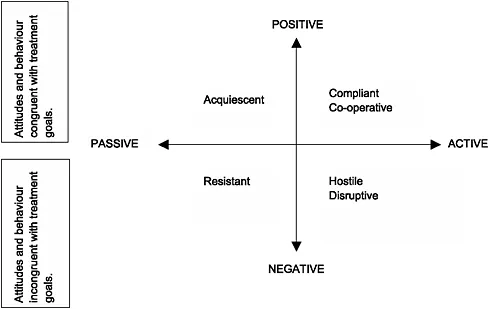

The concept of Participation attempts to provide an overarching framework, both encompassing broad service goals (attendance, engagement, termination of treatment, non-compliance and involvement in outpatient mental health settings), and a much more dynamic process, with clients actively involved in a treatment partnership, (Kazdin, Holland, and Crowley, 1997). This can best be seen in the two-dimensional model proposed by Littell, Alexander and Reynolds (2001) (see Figure 1.1).

This framework allows attitudes and behaviours to be perceived and categorised differently by clients and clinicians. This is a dynamic process, influenced by client beliefs, goals, external constraints and experience of services. These in turn are influenced by clinicians, settings, and social and cultural factors. A relationship that is positive and collaborative is seen as the best way of managing these complex influences. The way in which individuals view

these relationships, in other words the therapeutic alliance, is fundamental and likely to facilitate the successful delivery of interventions. The participation framework is clearly helpful in emphasising both the dynamic aspects of engagement and the centrality of the therapeutic relationship.

The concepts of Therapeutic Alliance, Compliance and Participation all help us to define what we mean by the term ‘engagement’ and how it relates to individuals and services. However, most research in this area has focused on clinician- or researcher-defined perspectives regarding what is important and relevant. The perspectives of clients and carers, who may similarly be poorly engaged with services, are equally valid.

Service user and carer perspectives

Qualitative studies exploring service user experiences (e.g. Priebe, Watts, Chase and Matanov, 2005; Bradley, Meaden, Tudway, Earl-Gray, Jones, Giles and Wane, in submission; Lukeman, 2003) reveal the following themes as important determinants of how service users engage with services:

• feeling in control

• a sense of being autonomous

• feeling enabled

• active participation

• time and commitment

• social support without a focus on medication

• a partnership model of therapeutic relationships: feeling equal, valued and heard

• being listened to

• being treated as an individual

• staff being interested and respectful

• gradualness

• consistency

• practical help

• clinical help.

These themes suggest that good engagement is fostered when there is a respectful enabling partnership that offers time, understanding and support. These factors help clients move from viewing assertive outreach as a service which has been imposed on them, to one that they can work with collaboratively (Lukeman, 2003). Gillespie, Smith, Meaden, Jones and Wane (2004) found that clients and clinicians rated the importance of items on the Engagement Measure (Hall, Meaden, Smith and Jones, 2001) differently, although there was some overlap. For example, clients who perceived their treatment as useful were rated as well engaged by staff, but not necessarily by clients themselves. Clients and staff agreed more on items which measured discussing personal feelings, active involvement with treatment and attending appointments.

In attempting to resolve conceptual issues and apparent differences between clinicians and clients as to what factors should constitute engagement, engagement can best be seen as a multi-dimensional process: