![]()

1

“Exploding the Myth of the Black Rapist”

Collective Memory and the Scottsboro Nine

The Negro women of the South lay everything that happens to the members of her race at the door of the Southern white woman… . if the white women would take hold of the situation … lynching would be stopped.1

Whether we like it or not, and whether it is just or not, this Scottsboro case is going to wipe out of the picture of the public mind all these other lynching investigations and the like, and by its outcome the South will be judged.2

In 1920, black female members of the Commission on Interracial Cooperation challenged their white counterparts by arguing that “when Southern white women get ready to stop lynching, it will be stopped and not before.”3 It is unlikely that they could have imagined that the most powerful answer to their call would come, more than a decade later, from a white woman whose fabricated claims of rape at the hands of nine black boys and young men had nearly prompted a mass lynching. Nor would this woman have appeared any more likely to answer the call just over a week after the mass lynching was averted, as a crowd of 10,000 spectators gathered outside of a courthouse in Scottsboro, Alabama, listening to a brass band playing Dixie, and cheering the guilty verdicts that would send eight of the “Scottsboro Boys” to death row. Certainly, no one who sat in the courtroom on April 6th, 1931, listening to Ruby Bates provide testimony that helped make these convictions possible, would have mistaken her for a civil rights icon. Yet it is difficult to think of any individual who had a more dramatic impact upon American understandings of race, gender and justice, or who played a more central role in the struggle for African American rights in the 1930s.

What has been widely referred to as “the Scottsboro Case” is actually a series of criminal trials, convictions, appeals, and further convictions stretching out over a seven-year period in the 1930s. The “Scottsboro Boys” (or the “Scottsboro Nine”) initially came to the attention of the Jackson County sheriff’s department after some of them had gotten into a fight with a group of white boys while riding the rails in northern Alabama.4 When the white boys lost the fight and were forced to leave the train, they went to the authorities to complain. Presumably outraged at the thought of black men who had the temerity to “offload” a group of whites, Sheriff M. L. Wann ordered his deputy to stop the train outside of Paint Rock, and to “capture every negro on the train and bring them to Scottsboro.”5 The deputy enlisted the aid of every armed man in the town. When the posse searched the train, among the passengers they discovered were not only nine African Americans, but also two white women, Victoria Price and Ruby Bates, dressed in overalls and wearing men’s caps.6 Bates was seventeen years old, and Price was a married woman traveling with a man who was not her husband. The most credible historical accounts suggest that it was in order to prevent possible prosecution for vagrancy, adultery, or for violations of the Mann act (forbidding the transportation of minors across state lines for “immoral purposes”), that Price and Bates decided to claim that they had been raped.7

The defendants were in the Scottsboro jail, thinking that they were to be charged for “assault and attempt to murder”—charges stemming from their fight with the white boys—for several hours before being put in a line up. It was only when they were identified by Price and Bates, who were asked to “point to the boys who had ‘had them’” that they realized they were to be charged with rape.8 As the prisoners started to learn the nature of their plight, a mob was gathering outside the jail. Several hundred armed men surrounded the prison, but the crowd dissipated when they learned that the governor had called out the National Guard to provide protection for the defendants. The reprieve was brief, however, since it was only a matter of days before all of the defendants had been convicted on the basis of little more than the often blatantly contradictory testimony of Price and Bates.9

The convictions were overturned on three separate occasions—once by a trial judge, and twice by the United States Supreme Court. The court ruled in Powell v. Alabama (1932) that the defendants had been denied effective assistance of counsel. Powell was the first in a series of cases leading up to two of the best known criminal justice decisions by the Supreme Court, Gideon v. Wainwright (1963), and Miranda v. Arizona (1966), holding that states must provide a lawyer to all indigent suspects and defendants, and that all suspects must be informed of their rights before questioning them in custody. And in Norris v. Alabama (1935), the second Scottsboro case to be heard by the Supreme Court, the Court ruled that Alabama jury commissioners had illegally excluded black jurors on the basis of their race. After Norris, and another series of trials, the state of Alabama dropped the charges against four of the defendants, who were finally released in 1937, while the other five remained in prison for lengthy sentences.

Because of efforts by the International Labor Defense (the legal arm of the Communist Party, henceforth, the ILD) to publicize the case, Scottsboro became an international cause célèbre, and there was a mass movement devoted to freeing the Scottsboro defendants that spanned much of the duration of the 1930s. Tens of thousands of protestors gathered in Moscow’s Red Square, while demonstrators condemned the verdicts in Havana, and marched on American consulates in Berlin, Leipzig, and Geneva.10 Ada Wright, the mother of one of the defendants, went on an international speaking tour to sixteen countries in six months, speaking about the case to nearly 500,000 people.11 According to the Communist Party, more than 300,000 protestors in over 100 American cities demanded the defendants’ freedom on May 1st, 1931.12 Prominent intellectuals, including Theodore Dreiser, Upton Sinclair, John Dos Passos, Albert Einstein, and Thomas Mann wrote letters or signed petitions opposing the convictions, referring to the case as a “legal lynching.” The movement was spurred on by favorable court decisions, and by Ruby Bates’s 1933 admission that she had never been raped. I will return to this admission.

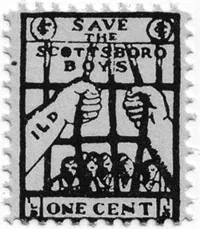

Much of the battle to free the defendants was waged through a struggle over the kinds of images that would be used to define the case against them. The ILD and the African American press were particularly interested in creating an anti-racist spectacle that would draw attention to the injustice of the case. To this end, they printed thousands of political cartoons about Scottsboro, and organizations within the Scottsboro defense movement circulated artwork about the case in every way that they could.13 The ILD incorporated the case into their fundraising, printing two million one cent stamps featuring a drawing of imprisoned men and two giant arms prying open the jail cell bars. “ILD” is written on one of the arms, and “Save the Scottsboro Boys” is printed at the top of the drawing (Figure 1.1).

The stamps were sold as the ILD collected membership dues, and they were frequently affixed to postcards (along with official U.S. postage) ensuring that U.S. postal workers, as well as the intended recipients of the postcards, would learn about the case.14 The black and Communist presses frequently fed off of each other, sharing resources to illuminate particularly galling examples of unjust treatment for the defendants. For example, the Daily Worker reported, in the early days of the case, that when a judge asked an attorney for the Alabama Power Company to defend the accused, he declared that his company was “in business to sell ‘juice’ to ‘burn Niggers’ and he welcomes that sale.” The Baltimore Afro-American picked up the story and, crediting the Daily Worker, ran a cartoon titled “Sells Juice to Burn Negroes” showing a grotesque, hunched-over, white man in a top hat and tails pulling the lever that would kill the black man we see sitting in an electric chair.15 The ILD published a series of Scottsboro-related pamphlets, which invariably included artwork and photographs intended to humanize the defendants and draw attention to the power and necessity of the defense movement. Pamphlets might feature photographs of the defendants as young children, or of their mothers or childhood homes.16 One particularly elaborate pamphlet combined a series of sketches with narration to tell “The Story of Scottsboro in Pictures.” The cover illustration depicts two broad-shouldered men swinging axes in the direction of a tree that has the word “Lynching” scrawled over its middle. The tree appears ready to topple, and the word “Scottsboro” is written underneath the men, who are presumably members of the Scottsboro defense movement, chopping away at the foundation of lynching and its attendant horrors.17 White southerners who were either convinced of the defendants’ guilt or resentful of communist and northern interference did not cede the ground of imagery, and fought back with their own cartoons, and with photographs that were chosen to highlight a variety of threats posed by the defendants. For example, a book on the case called Scottsboro: The Firebrand of Communism included photographs of “a sullen, menacing Haywood Patterson, with a sug-gestive gaping hole in the crotch of his trousers” along with photos of several of the other defendants dressed in clothes that were labeled “urban,” with the suggestion that they were “financed, no doubt, by … liberal and Communist supporters.”18

Figure 1.1 International Labor Defense (ILD) Assessment Stamp, 1931.

Source: Collection of the Author.

The interest in the case was never limited to the nine defendants and two accusers. Instead, virtually everyone involved in the case saw the alleged rapes in symbolic terms. For the prosecution and the white southern press, at least in the early stages of the case, the issue was always about protecting the southern way of life in general, and “southern womanhood” specifically. One prosecutor declared in his closing arguments that the defendants had “hurled a challenge against the laws of Alabama, the sovereignty of the State and the sanctity of white womanhood,”19 while the prosecutor in another trial told jurors not to “quibble over the evidence,” since “the womanhood of Alabama was looking to them for protection.” Victoria Price, he shouted, was fighting “for the rights of the womanhood of Alabama.”20 For the Communist Party, the case provided graphic evidence of the nature of capitalist oppression and class struggle:

Like the allegorical plays of the middle ages the characters represented not only themselves but powerful forces, gigantic forces locked in combat. The force of the Southern white ruling class, backed by their brothers all over the capitalist world, determined to perpetuate the system on which they flourish, the system of slavery and terror, of oppression and lynching. And the force of the toiling masses, workers and farmers, of all colors and creeds, determined that the system under which they are exploited and crushed, shall be destroyed.21

For many members of the broader Scottsboro defense movement, and for much of the black press, the case was framed in stark racial terms. Looking back on the victories of the movement, Richard Wright wrote that

We were able to seize nine black boys in a jail in Scottsboro, Alabama, lift them so high in our collective hands, focus such a battery of comment and interpretation upon them, that they became symbols to all the world of the plight of black folk in America.22

Only the NAACP, which fought with the ILD over the right to lead the defense in the case, expressed concern about the idea of seeing the principals in the case as symbols. The Association was concerned that in using the case to mount an assault upon white supremacy, or capitalism itself, the ILD was jeopardizing the lives of the defendants. The Crisis (the NAACP’s magazine) editorialized that

A frontal attack on Alabama and the whole southern system, with trumpets blowing, banners flaunting, and short swords gleaming bravely against the baleful glare of the Dragon Prejudice makes a fine spectacle, but in the encounter it was inevitable that the lives of the Scottsboro youths became of secondary importance in the minds of Alabamians.23

Later, the magazine argued that “these helpless boys did not ask to be made martyrs for the sake of the cause of Communism, or for the sake of the Negro race, or for the sake of anything. They want to be free!”24 While the cost of becoming symbols was important to weigh, the publicity generated by the case was a key factor keeping the defendants out of the electric chair, and in eventually winning their release from prison.

Trying to determine when the case ends is tricky. One might point to the Alabama Supreme Court’s decision to uphold the death sentence for one of the defendants, Clarence Norris, in June of 1938, or to the reduction of that sentence to life imprisonment by Alabama’s Governor in July of the same year. But it might make more sense to look to June of 1950, when the last of the “Scottsboro Boys” was paroled, after the defendants had spent a combined 104 years in prison. Those looking for a sense of historical justice might turn to October, 1976, when Alabama’s Governor George Wallace, having long abandoned his vow “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever,” licking his wounds after being forced to drop out of the Presidential election, and contemplating his political future, agreed to sign a pardon for Clarence Norris, in effect, according to Alabama law, declaring him innocent of all charges. But, perhaps the most appropriate place to look for an end to the case is decades earlier, in 1952, the year that marks the first death of a Scottsboro defendant. Sixteen years after he was first arrested, Haywood Patterson had finally escaped from prison in 1947. By 1950, having lived all but three years of his adult life in prison, he was back behind bars, and was eventually convicted of manslaughter in a barroom brawl. He became ill, and ultimately succumbed to cancer, dying in the Michigan state penitentiary. He was thirty-nine years old. If none of these dates seems to adequately mark the conclusion of the case, one might finally take a more philosophical stance and suggest that the case never really ended, and instead lives on as memory, reverberating throughout later struggles for racial justice and helping to shape the contemporary racial l...