![]()

Toward a Technics of the Flesh

![]()

Bodies in Code, or How Primordial Tactility Introjects Technics into Human Life

Artificial realities are based on the premise that the perceptual intelligence that all men share is more powerful than the symbol manipulation skills that are the province of the few.

Myron Krueger1

1. “Make Use of What Nature Has Given Us!”

If Myron Krueger deserves to be heralded as the pioneer of interactive media art, this has more to do with the aesthetic qualities of his interactive platform than its undeniable technical contribution. From the beginning,Krueger’s interest concerned the enactive potentialities afforded by the new media and not their representational or simulational capacities.He recalled this commitment in a recent interview:

In 1970, I considered HMDs (head mounted displays) and rejected them because I thought whatever benefit they provided in visual immersion was offset by the encumbering paraphernalia which I felt would distance participants from the world they were supposed to feel immersed in. When I pondered what the ultimate experience would feel like, I decided that it should be indistinguishable from real experience. It would not be separated from reality by a process of suiting up, wearing gear, and being tethered to a computer by unseen wires.… Rather than limiting your participation to a single hand-held 3D pointing device, your image would appear in the world and every action of your body could be responded to instantaneously. Whereas the HMD folks thought that 3D scenery was the essence of reality, I felt that the degree of physical involvement was the measure of immersion.2

In an artistic (and engineering) career wagered on this commitment, Krueger has quite literally sketched out an alternative trajectory to that followed by mainstream virtual reality research, art practice, and cultural ideology. Rather than investing in the simulational power of the image and the ocularcentric paradigm of immersion, Krueger has staked everything on the constructive power of (human) embodiment. For him, virtual reality technologies are important, indeed momentous, not because they lend new, stronger material support for the image (whether it is conceptualized in the frame or the panorama traditions), but precisely because they extend the body’s power to construct space and world.

In this deployment, technologies work to expand the body’s motile, tactile, and visual interface with the environment; to do so, they call upon—and ultimately, refunctionalize—the body’s role as an “invariant,” a fundamental access onto the world, what psychologists and phenomenologists have called the “body schema.” In this way, digital technologies lend support to a phenomenological account of embodiment and expose the technical element that has always inhabited and mediated our embodied coupling with the world. Indeed, as we shall see, they add a technohistorical basis to the claims of those contemporary researchers who not only align the body schema with proprioception but also propose this latter as a sixth (and more fundamental or somehow originary) sense.

This subordination of technics to embodied enaction motivates (and licenses) me to position Krueger as the precursor—and first practitioner—of second-generation virtual (or mixed) reality. Together with the more interesting digital artists of today (indeed, in many cases, as a direct inspiration to them), Krueger views and deploys the virtual less as an alternate, body-transcending space than as a new, computerenhanced (if not in some important sense, computer-facilitated) domain of affordances for extending our evolutionarily accomplished interface with the world. Understood against this background, Krueger’s renegade act of renaming can be seen to mount an aesthetic, indeed properly philosophical, challenge to the mainstream. As Krueger explains, the term “artificial reality” more aptly captures how “virtual reality” functioned, not simply or primarily as a technical platform, but rather as a “metaphor for what was happening throughout our society” (Turner).

Yet, if Krueger’s theory and work resonate with the second-generation paradigm of mixed reality, this is due less to his original aim (provoking the flat-footed humanism of the art worldi) than to the singular convergence of the “artificial” and the “natural” in the electronics technologies ubiquitous in our world today.ii This is a reality not lost on Krueger, who has recently noted: “Since I was arguing for convenience, naturalness, and obviousness, my concepts were well-positioned for technological advances as they unfolded. Since 99% of applications are 2D and 99% of 3D applications are driven by 2D interfaces, there has been very little immediate interest in HMD immersion systems in the general office environment,” not to mention the world beyond. As if echoing (or ventriloquizing) the proponents of the mixed reality paradigm, Krueger speaks of a “progression towards external realities” driven by the technical development of low-cost projectors and organic LED displays that can be ubiquitously embedded in the environment; rather than withdrawing from the physical domain, today’s digital technologies are literally virtualizing the physical.

Krueger’s calculated defense of the artificial notwithstanding, the operative principle of his research and artistic experimentation could easily be summarized in the form of a practical maxim: make use of what nature has given us! “In our physical reality,” Krueger observes, “We use our bodies to interact with objects. We move our bodies or turn our heads to see better. We see other people and they can see us. We have acquired a consistent set of expectations through a lifetime of experience” (148). Making use of this evolutionarily realized heritage will allow us to adapt to our ever more rapidly changing technical environment because such heritage provides a stable background against which to assimilate new interactional spaces and share new affordances: “Any system that observes these conventions will be instantly understood by everyone on the planet” (148).

More than a simple desire to buck the technicist trend, Krueger’s work is informed by his conviction that the best way for us to bring technologies to bear on human existence—to shepherd our ongoing technogenesis as it undergoes its most accelerated phase to date—is to channel them through our evolutionarily acquired embodiment. This explains his lifelong commitment to a humanist model in which human interaction (encompassing interaction with the self, with others, and with machines) prevails over any notion of technicist instrumentalization. Krueger’s environments function practically, following the characterization of Howard Rheingold, as “laboratories for finding out how humans might harmonize with” technical environments whose sway is (and has always been) inescapable.iii,3

The benefits of such an artistic (and scientific) program are twofold: On one hand, human embodiment serves to “naturalize” technical modifications of the world (and, potentially, of the body); on the other hand, these modifications provide an important source for decoupling or deterritorialization by which the body’s habitual intercourse with the world gets disturbed and (potentially) expanded. Embodiment accommodates and self-reorganizes in the face of the ever expanding scope of technics in our world today.

In a series of works culminating in the ground-breaking video projection system Videoplace, Krueger has sought to materialize his conviction that “the focus of interface research should be on human nature, not on the transient computer” (Krueger, “An Easy Entry,” 147). This conviction has led him to construct environments that eschew the logic emanating from computer code in favor of emergent logics rooted in social conventions. Never an end in itself in Krueger’s work, the computer is always a vehicle for exploring and expanding embodied (human) interaction with the world and with other human beings. “In the ultimate interface,” he stresses, “input should come from our voices and bodies and output should be directed at all our senses. Since we will also interact with each other through computers, the ultimate interface should also be judged by how well it helps us to relate to each other” (147).

This principled emphasis on human embodiment as mediator between computer and world represents something new in the history of our technogenesis: in its role as primary access to a (now) highly technologized lifeworld, embodiment serves to couple body and world, as well as to actualize the potential of digital (virtual reality) technologies to modify the lifeworld (and, thereby, to infiltrate that primary enactive, worldconstitutive coupling). Embodied enaction is, quite literally, the agent through which technics has an impact on life and the lifeworld.

If Krueger’s entire career seems dedicated to exposing nothing more or less than this primacy of embodied enaction, the latter—as he points out—ushers in an important, and enabling, margin of indetermination: “The logical consequence of this thought process [yielding the conception of the ultimate interface] was the concept of an artificial reality in which the laws of cause and effect were designed to facilitate the functions that interested the user” (148). It would hardly be an exaggeration to claim that this margin of indetermination—one directly tied to technics—comprises the operative principle of Krueger’s embodied aesthetics of new media. The new technical environments afford nothing less than an opportunity to suspend habitual causal patterns and, subsequently, to forge new patterns through the medium of embodiment—that is, by tapping into the flexibility (or potentiality) that characterizes humans as fundamentally embodied creatures.

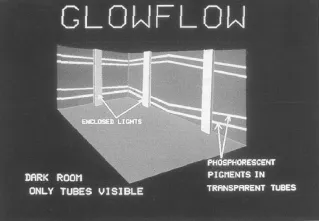

That this principle comprises the explicit focus of Krueger’s first, predigital responsive environment amply attests to its centrality in his aesthetics. Glowflow (1969) is a light–sound environment—a room with four horizontal light tubes running along its walls—that deploys visual and auditory means to disturb the visitor’s habitual mode of perceiving space (see Figure 1.1). The room is entirely dark except for the multicolored phosphorescent light tubes which form the only visual point of reference for the visitor. Movement within the darkened space inevitably causes the visitor to step on floor sensors that release into the tubes light and sound elements from one of four enclosed light columns (one per tube). Outside of this element of interactivity, the pigments running through the tubes remain arbitrarily determined.

Figure 1.1 Myron Krueger, Glowflow (1969), light–sound reactive environment that deploys visual and auditory means to disturb the visitor’s habitual mode of perceiving space. (Courtesy of the artist.)

What proved compelling about the environment and most captivated Krueger’s aesthetic interest was the way that viewers inevitably, one might even want to say “naturally,” attempted to make sense of the environment by coupling intentional gestures (e.g., speaking or moving) with the (mostly arbitrary) patterns of light in the tubes. As Krueger recounts in Artificial Reality 2,

If a tube started glowing after [the visitors] spoke, they would assume that their speech had turned it on. If a sound occurred after they hit the wall, they would assume that striking the wall would elicit more sounds. Often, they would persist in the behavior long after the result should have convinced them that their hypotheses were incorrect.4

This emergent and unexpected phenomenon alerted Krueger to the possibility and value of exploiting the margin of indetermination afforded by experience with new technologies and media environments.iv As Söke Dinkla has observed,

The behavior of the visitor comprised efforts to figure out the rule system of Glowflow. The process of rational clarification of cause and effect proceeded precisely opposite to its normal pattern: an effect would dictate its cause and not the reverse [Einer Wirkung wurde eine Ursache zugeschrieben und nicht umgekehrt]. Such exploratory behavior is typical when it is a question of accommodating oneself to foreign surroundings whose rules are unknown. (67)

In one way or another, all of Krueger’s environments exploit this technique of disturbing habitual cause and effect couplings to domesticate novel experiential domains through the primary medium of embodiment.

With his subsequent (and properly digital) environments, however, Krueger added a crucial element to this technique of domestication: the calculated feedback of new sensory experiences into embodied enaction for the express purpose of expanding the latter’s agency (together with the scope of its coupling with the environment).v What made this possible and served to distinguish Krueger’s environments from the majority of art environments from the 1960s was Krueger’s insistence on clarifying for the visitor precisely how his or her actions called forth reactions from the environment. Because this insistence is due, in part at least, to the analytical precision afforded by the computer as a material support for the interactive environment, it yields a specific, technical (but not technicist) conception of interactivity: “dealings [einen Umgang] with the computer in which the receiver/user is able clearly to correlate her actions with the reactions of the system” (Dinkla, 70). Such correlation, affirms artist Simon Penny, comprises “the first and fundamental law of the aesthetics of interactive installation” (Simon Penny, email to the author, January 3, 2006).

On this conception, interactivity can be distinguished from prevailing notions of the period and from more contemporary technicist visions. It is at once more codified than the radically open-ended environments of process art and happenings and yet more open and flexible than the preprogrammed response repertoires that one finds in so-called interactive cinema and hypertext. What is crucial in Krueger’s conception of interactivity, as in his humanist conception of artificial reality more generally, is the privilege accorded embodied (human) agents. Differences notwithstanding, the point of all of his environments is to facilitate new kinds of world-construction and intersubjective communication. If these environments do still serve as interfaces to the computer, they do not do so, as do all technicist conceptions of the “Human–Computer Interface” (including the mouse and the graphicaluser interface), by instrumentalizing—and thus reducing—embodied enaction; here, rather, it is the technology that remains instrumentalized and human action that gets privileged.

From 1970 to 1984 (when he ceased development of his interactive platform, Videoplace), Krueger devoted himself to the task of producing an environment that would realize the potential of the computer to expand human capacities for embodied enaction and communication. Not surprisingly, this realization—accomplished in Videoplace—proceeded through several discrete stages, each of which marks an important advance in the transfer of agency from the computer to embodiment in open-ended feedback with itself.

Metaplay (1970) combined closed-circuit (video) technology with the computer to explore the conditions for the correlation by the visitor of her actions ...