- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

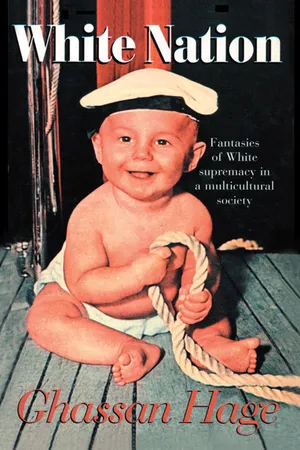

Anthropologist and social critic Ghassan Hage explores one of the most complex and troubling of modern phenomena: the desire for a white nation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access White Nation by Ghassan Hage in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Media Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1 Evil White Nationalists 1: The Function of the Hand in the Execution of Nationalist Practices

DOI: 10.4324/9780203819470-1

‘I just saw her hand, she pulled my hair and my scarf violently, pushed me and started shouting abuse …’ This is how Siham recalled experiencing her scarf being ripped off her head by an ‘Anglo’ woman in a Sydney supermarket during the Gulf War. Incidents such as the tearing off of the scarf, along with many other acts of harassment directed at Arab and Muslim Australians, were widely reported as examples of ‘racism’ or ‘racist violence’ in the Australian press and in government reports at the time. The tearing off of scarfs was the most common incident registered in a report, Racist Violence, which followed from the government-financed National Inquiry into Racist Violence in Australia (NIRVA). According to NIRVA:

There have been widespread reports of Muslim women having their hijab pulled off in the street; such attacks are more significant for their symbolic impact on the victim than for any physical harm they may do.1

In one case, in Melbourne, it is reported that an ‘Anglo’ woman ‘deliberately drove into the vehicle driven by the Muslim woman wearing traditional Islamic dress, and then verbally abused her, accusing her of being an Iraqi terrorise.2 In another case reported in the Australian Bulletin magazine:

Two women, one with her children, are sitting in their car in a supermarket in a Sydney suburb. Both are wearing the hijab (Muslim headscarf). A man unknown to them drives up, rams their car, gets out, drags one of the women out and beats her to the ground before speeding off.3

There were many other incidents reported by the press and various anti-racist bodies, such as the burning of mosques and the throwing of rocks through Muslim shop windows.4 The NIRVA report also lists other incidents such as ‘Arabs and Muslims being spat on in shopping centres, and being taunted while walking or driving’ (p. 146); all of these are classified as ‘racist violence’.

While such practices and their like are clear acts of racist violence for all practical political purposes, in this chapter, I want to question the extent to which they are best characterised this way for analytical purposes. I will analyse their structure and their constituent elements: What do they aim to achieve? How do the people who execute them experience themselves? How do they classify Muslims while performing them? I will argue that there is a dimension of territorial and, more generally, spatial power inherent in racist violence that the categories deriving from the concept of ‘race’ cannot by themselves encompass. While such practices are ‘informed’ by racist modes of classification, I will maintain that they are better conceived as nationalist practices: practices which assume, first, an image of a national space; secondly, an image of the nationalist himself or herself as master of this national space and, thirdly, an image of the ‘ethnic/racial other’ as a mere object within this space.

In making this claim, I am not only concerned with raising a technical analytical issue. The importance of highlighting the nationalist dimension of such ‘racism’ is that it will allow us to demystify the exaggerated way in which the dominant culture tries to distance itself from it by obscuring the fundamental features they both share with a moralistic divide between ‘evil racism’ and ‘good tolerance’.

Racism and the Question of Practice

The sociological tradition has a long history of perceiving ‘racism’ as a mental phenomenon in abstraction from the possible practices through which it can be articulated. It is generally considered as a system of beliefs, a mode of classification or a way of thinking. Furthermore, it is invariably considered as an ‘evil way of thinking’ about the ‘self’ and particularly about the ‘other’. It is perceived as ‘evil’ both logically and politically. Ruth Benedict was one of the first to conceptualise it in this way, defining racism as a ‘dogma’ that maintains the ‘congenital inferiority’ or superiority of certain groups.5

From this perspective, one is confronted today with a multitude of definitions of the concept. There are disagreements over whether the term ‘racism’ should be reserved for traditional ‘biological’ forms of racism6 or be extended to recent culturalist conceptions used to exclude people.7 There are also tensions between the perception of racism as a ‘political ideology’ in the sense of a system of thought with its established ‘theorists’ such as ‘scientific racism’ and its conception as a mode of thinking present in commonsense, undertheorised forms within everyday life interactions.8 There is general agreement, however, that racism involves a simplification of the determinants of collectively shared behaviour.

The work of the French sociologist Pierre-André Taguieff (1987), which is by far the most extensive and systematic attempt to review the many definitions of the term, gives a clear idea of the magnitude of the field of definition: racism as attitude, racism as ideology, as prejudice, as xenophobia, as naturalisation, biological racism, ethnic racism, essentialist racism, assimilationist racism, competitive racism, auto-referential racism, altero-referential racism, differential racism, inegalitarian racism and more either compete or coexist with each other in a variety of combinations vying to give a proper description of the ‘essence’ of the phenomenon.9

Despite the important insights it has allowed, this general and dominant tendency to define racism as a mental phenomenon has continually led to an undertheorisation of the relationship between the mental classification involved and the practices in which they are inserted, between what racists are thinking and what they are doing. We find a good example of the problems raised by such an approach in a much-used definition by Bob Miles, where he argues:

The concept of racism refers to those negative beliefs held by one group which identify and set apart another by attributing significance to some biological or other ‘inherent’ characteristic (s) which it is said to possess, and which deterministically associate that characteristic (s) with some other (negatively evaluated) feature (s) or action(s). The possession of these supposed characteristics may be used to justify the denial of the group equal access to material and other resources and/or political rights.10

Miles's main concern here is to clarify the conceptual field. He devotes most of his attention to a ‘tight’ description of the internal logic of a dominant form of racist thought. He wants to disallow a sloppy usage of the category ‘racism’, or what he later called ‘conceptual inflation’.11 Despite the tightness of the definition in most of the paragraph, however, as soon as we arrive at the relationship between racism and practices, the text becomes considerably vague: ‘these supposed characteristics may be used’. Are racist categories sets of classification that are simply hanging ‘out there’ to be used or not used? To what extent can one posit classifications that remain unchanged by their usage?

In The Logic of Practice, Pierre Bourdieu criticises what he sees as the intellectualist reduction of ‘the [practical] logic of things’ into ‘things of logic’, and the treating of practical knowledge as if it has no other reason to exist than an intellectual one.12 What Bourdieu means is that academic sociologists, by virtue of their profession, have a specific interest in, or a specific ‘take’ on, the beliefs and statements made about the social world. They often want to know whether such statements are true or false, whether they provide a good description or explanation of whatever it is to which they are referring. This is the logic that governs the statements sociologists themselves produce about the social world, and many of them end up assessing all statements about the social world using such criteria: are they true or false, are they good descriptions or are they not, are they good explanations or are they not? In so doing, Bourdieu argues, such sociologists assume that all knowledge about the social world has a sociological purpose. They forget that knowledge for most people who produce it has a practical purpose. It helps people do things. This practical function of knowledge — does it help me do what I want or does it not? — is a far more important criterion of truth and falsity in the practical world than the sociological mode of ‘explanation for explanation's sake’.

I think Bourdieu's critique is of immense importance for the sociology of racism. When one examines the categories sociologists used to qualify racist beliefs — essentialisation, simplification, false, ideological, etc. — one can clearly see that what is assessed is whether racist statements are good sociological explanations. These categories fully exhibit the sociological failure to integrate the fact that popular racist categorisations are not out to explain ‘others’ for the sake of explaining them. They are not motivated by some kind of academic yearning for knowledge. They are categories of everyday practice, produced to make practical sense of, and to interact with, the world. Using them, people worry (in a specific, racist way) about their neighbourhood, about walking the streets at night, about where they can do their shopping and what kind of shops are available to them and so on.

What is the relation between the practices in which racist classifications are used and the classifications themselves? Do racist classifications define the nature of the practices to which they become articulated or are they merely a support towards achieving different ends? That is, do people use racism to achieve various practical goals, or is the main aim the assertion of the superiority of the race every time there is a racist classification in usage? Such questions related to practices and everyday deployment of racist categories are not systematically discussed in the literature on racism.

In a sense, for a more dynamic, practice-grounded, conception of racism, Gordon Allport's social psychological approach is more pertinent for our purposes. It leads him to differentiate between a variety of racist behaviours: verbal rejection, avoidance, discrimination, physical attack, extermination. From this, one gets a better sense of how racism is put into practice.13 This raises an even greater difficulty, however, and one which is of more direct concern to us. In what way are such practices as rejection, discrimination or physical attacks ‘racist practices’? We can all agree, for instance, that tearing a Muslim women's veil off her head is a physical attack. We can also agree that this attack is informed by a negative racist conception of a Muslim woman, even if this is not explicitly formulated by the person doing the tearing. Does this, however, make the attack primarily racist or racially motivated?

Of course, to a certain extent, any usage of racist classifications can be said to be racially motivated. The question, however, is how does this motivation relate to other motivations? If a White footballer, while tackling a Black opponent, emits a racist slur in the heat of the action, does the tackle stop being a football tackle and turn into ‘racist violence’? Is the footballer's action ‘racially motivated’ or ‘football motivated’? The fact that he used the racist slur may make him a racist, but does it mean that he is now playing a game called racism and that he is more concerned with asserting the superiority of the ‘White race’ than with playing football?

The trouble with the concept of ‘racist practices’ or with ‘racially motivated’ practices is that the belief in races or ethnicities, even the belief that there is a hierarchy of races or cultures, is not in itself a motivating ideology.14 Racism on its own (like sexism in this regard) does not carry within it an imperative for action. One can believe that there is a White race or a Black or a Yellow race. One can even believe that the White race is superior to the Black and Yellow races. There is nothing in this belief, however, that requires one to act against members of the supposed Black or Yellow race. I can believe that Blacks and Asians are radically different or inferior without caring about where they live, whether they sit next to me on the train or whether there are ‘too many of them’. As soon as I begin to worry about where ‘they’ are located, or about the existence of ‘too many’, I am beginning to worry not just about my ‘race’, ‘ethnicity’, ‘culture’ or ‘people’, but also about what I consider a privileged relationship between my race, ethnicity and so on, and a territory. My motivation becomes far more national than racial, even if I have a racial conception of the territory. This is why I want to suggest that, from this analytical perspective, and in so far as they embody an imagined special relation between a self and a territory, such practices are better conceived as nationalist practices than as racist practices, even if racist modes of thinking are deployed within them.

Racism and Power

One approach which appears closer to coming to grips with the question of practice is often formulated by intellectuals from racialised minorities. The dissatisfaction with conceptions of racism as a ‘floating’ mode of classification detached from practices and relations of power has been often expressed by such intellectuals.

One reason for this dissatisfaction is that an understanding of racism as essentialisation or stereotyping has frequently lead to counterclaims, often by those accused of racism, that ‘Everybody's racist.’ This is meant to emphasise that it is not only the majority that engages in racial stereotyping and essentialisation or even inferiorisation. To this, minority intellectuals have responded by emphasising that power is a far more distinctive dimension of racism than particular ideologies. So, to the claim that ‘Everybody's racist’, the answer of these intellectuals has been that, while everyone may be capable of stereotyping and essentialising others, not everyone is capable of using their racism to discriminate and subjugate others. Only the latter really qualifies as racism.

Thus, in England, Sivanandan stresses that ‘racism is about power not about prejudice’.15 Likewise, in the United States, black militants such as Carmichael and Hamilton see racism as ‘the predication of decisions and policies on consideration of race for the purpose of subordinating a racial group and maintaining control over that racial group’.16 In pointing to such questions of power in relation to racist modes of classification, these pronouncements help us to acknowledge their presence. This is already an important achievement. This power dimension is not, however, really treated satisfactorily.

Part of the problem is that the intent of such pronouncements is far more political than sociological. Anti-racist interests in an anti-racist politics and the sociological interest in explanation do not necessarily go together, as so many anti-racist sociologists like to believe. I will be treating the relation between the two more extensively in the conclusion. At this point, it is important to recognise that for intellectuals such as Sivanandan, Carmichael and Hamilton, the category ‘racism’ is an indicator of an existing racially defined and experienced social problem of inequity and domination in society. As such, their concern is to centre our attention on this problem and not allow a watered-down conception of racism to efface it. In this sense, they are totally correct in their emphasis.

In highlighting the question of power, they emphasise that if everyone can entertain prejudiced fantasies about a variety of ‘others’, it is the power to subject these ‘others’ to your fantasies that constitutes the social problem and, according to them, that is to what ‘racism’ ought to refer. They are right as to where the more important social problem lies, but it is not sociologically clear why this social problem has to be referred to as ‘racism’ except for the political reason that there are negative connotations historically associated with the word.

Indeed, in the course of the interviews I have been conducting since the Gulf War, it has become quite clear that the way a number of Arab migrants think about Anglo-Celtic Australians is far from being free of stereotyping and essentialisations — and is not particularly flattering. Views that ‘Australians’ are too inclined to drunkenness and uncommitted to their families, and statements that ‘They walk barefooted like beggars’, ‘They don't clean their houses properly, they are always dirty and dusty’, ‘Their houses smell because they never open their windows’, as well as a whole array of views concerning the lax moral standards of ‘Australians’, especially when it comes to raising children and questions of sexuality, were not uncommon. In this sense, those Arab Australians were just as racist as the Australians from the dominant White culture who were classifyi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- preface

- introduction

- chapter 1 Evil White Nationalists 1: The Function of the Hand in the Execution of Nationalist Practices

- chapter 2 Evil White Nationalists 2: The‘White Nation’ Fantasy

- chapter 3 Good White Nationalists: The Tolerant Society as a ‘White Nation’ Fantasy

- Appendix to Chapter 3

- chapter 4 White Multiculturalism: A Manual for the Proper Usage of Ethnics

- chapter 5 White National Zoology: The Pro-Asian Republic Fantasy

- chapter 6 Ecological Nationalism: Green Parks/White Nation

- chapter 7 The Discourse of Anglo Decline 1: The Spectre of Cosmopolitan Whiteness

- chapter 8 The Discourse of Anglo Decline 2: The Role of ‘Asians’ in the Destruction of the ‘White Race’

- chapter 9 The Containment of the Multicultural Real: From the ‘Immigration Debates’ to White Neo-Fascism

- endnotes

- bibliography

- index