![]()

CHAPTER 1

All For Art

THE MALE NUDE IN THE SERVICE OF ART

The relationship between the fine arts and photography has always been uneasy, even in photography’s earliest days, and nowhere more forcefully than in images of the male nude. As Clarence Norwood, an advocate of nudism, wrote in 1933, ‘the study of the nude has always been regarded as a legitimate branch of plastic art. Why this should be so has never been convincingly explained.’1 In western art, the male nude has held pride of place since classical antiquity. It was accepted by artists as a form which was thought to embody the finest proportions and the most satisfying shape. Renaissance artists saw the idealised male body as that created by God in His own image, hence great importance was given to its appearance and the nude was regarded as the main form for study in the training of artists. There was a convention that artists and spectators could view the nude as a work of art, an object without sexuality or sensuality concerned only with the deeper spiritual aspects of human aspirations.

While it was artistically and socially acceptable for painters and sculptors to make drawings, models, even to take photographs of the naked male body and occasionally to exhibit such work, the nude body in virtually any other public context was likely to be considered immoral or indecent. For most people the only opportunity to see the nude was in a form mediated by the artist, whether on the walls of art galleries or presented in three-dimensional form as sculpture. As Norwood pointed out, ‘the average member of the public has little or no chance of comparing the artistic product with reality.’2

The invention of photography challenged many of the basic creative processes of art, not only by seeming to do mechanically what took the artist years to accomplish, but also by affecting the way art was perceived (paintings could be ‘measured’ against photographs), how it was presented (by the cropping of the image or by the appearance of the freeze frame, for example) and what was acceptable as the content of art. Photography, by its apparently objective nature, its apparent ‘truth to fact’, in particular the emphasis on naturalism, and its ability to reproduce reality as seen by the eye, seemed to strike directly at the creative impulse and individuality of the artist, and indeed at the whole history of painting.3

Much of the appreciation of photography was founded on the belief that the new medium, which required an elaborate scientific process, told ‘the truth’.4 The camera, it was thought, did not merely picture, but it formed a surrogate world of hitherto unparalleled accuracy. Some artists realised perfectly well that the camera always had to be directed and manipulated, and that ‘the truth’ it told could be as subjective as that of any other art form. Nevertheless the photographic image carried great conviction in capturing ‘reality’. Some artists resisted its influence, but all were, to a greater or lesser extent, affected by it. In The Studio (1893), the editor published the results of a survey in which he asked leading contemporary artists whether they thought the camera was beneficial or detrimental to art.5 Leaving aside the fact that the camera had been in use by many artists, either openly or in secret, for some forty years, and the camera obscura for many years before that, the question naively omitted to recognise the effect the photographer’s image had had on art, whether artists were aware of it or not. The published replies ranged from those which acknowledged the benefits of the photograph to those which totally deplored it, while others suggested that its usefulness depended on the skills of the artist. Attitudes extended from a patronising condescension to a rather jealous derision. For many artists, however, the camera was seen for what it was: a useful means for picturing the material world with clarity, simplicity and precision, a mirror or a window on to the ‘real world’.6

A few artists and critics recognised the medium as an integral part of the creative process which had changed for ever the perception and understanding of art. Four major influences of the photograph can be identified. The first is that of the documentor, recording and preserving movement and likeness, a ready and convenient source of reference. The second is the influence on ‘ways of seeing’ introduced by the camera. These include the freeze frame, cropping, sequences of movement and the hyper-realism of the photographic image. ‘Ready-mades’ make up the third, with images from established photographic genres incorporated or reproduced in works of art. The fourth is the complete integration of the photographic image into the work of art so that the two are intimately bound and no separation can be made between them. In this work the photograph not only serves as a ‘window on the world’ but also illuminates and changes that vision.

For artists working from the nude, the camera proved to be of great practical help. Studies of particular poses could be taken and kept to hand until required and ‘difficult’ poses could be recorded for longer study. They were also far less costly to purchase or to commission than continually hiring a model. Scientifically the photograph revealed more than could be seen by the eye, and this detail and accuracy were to have a profound effect on the way artists saw and represented their subjects.7 As a range of photographic studies became widely available and particular genres of photographic work were established, artists started to use the presentation of the photographic image as their starting point, a direct stimulus to the imagination.

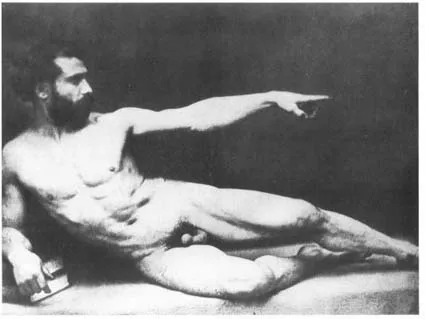

One of the first artists to welcome the discovery of photography and recognise its profound influence on art was the French romantic painter Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863).8 A collaboration with the photographer Eugène Durieu (1800–1874) resulted in a range of studies of specially posed naked men and women which the artist used for his painting [1]. Delacroix, one of the most intelligent and influential artists of the nineteenth century, maintained that ‘the study of the daguerreotype if it is well understood can itself alone fill the gaps in the instruction of the artist’.9 Fiery, temperamental and romantic (he described himself As a rebel rather than a revolutionary), he was quick to recognise the value of the photograph and regretted that he had not learnt the processes. Acting as a sort of art director, he arranged the models in carefully worked out poses for Durieu to photograph. The static positions were largely imposed by the technical requirements of photography. In his journal for the period 1853–4, Delacroix describes his desire for photographs which could if necessary serve as ready substitutes for live models; he also mentions borrowing daguerreotypes of male nudes taken by Jules-Claude Ziegler, a student of Ingres.

An album containing thirty-one photographs of the nude made by Durieu is in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.10 Many of these feature Thévelin, a muscular, dark-haired man in his mid-twenties who is shown fully naked. In some pictures he is accompanied by an equally naked woman. The style is clear and uncluttered and the poses heroic rather than ‘natural’, an impression heightened by the presence of a leopard skin or a staff. The images retain the clarity of the outline of the body and the well-placed lighting reveals the musculature. Showing the models in various poses, leaning first to one side and then to the other, they set the style for much of the photography produced for the use of artists throughout the century.

Despite the reluctance of most artists to paint the male nude, there was a demand for nude photographs. Academic life studies drawn or painted from the naked model continued to be accepted as the crucial part of the artist’s training. William Etty (1789–1849) was one of the few artists to consistently employ male nudes as subjects shown within classical contexts: he made use of photographs for portraits and may also have used them for his paintings of male nudes.

Delacroix well understood the value of photography to his work, not only as documentary but also as a means of simplification which could provide other and beneficial ways for artists to present ‘reality’. This mechanically dictated selectivity of photography was not, he thought, to be confused with the far more complicated, mysterious working of human memory and imagination; the unenlightened adherence to ‘fact’ offered by the camera did not achieve the more profound truths of which only artists were capable. Delacroix saw photography as having an essentially mechanical character which may or may not have artistic possibilities. His commitment to the new medium led him to become a founding member of the first national photographic

2 Guglielmo Marconi, Adam, c.1860–70. Study for artists.

society in France (Société Héliographique) in 1851. Nevertheless, he did not see photography as carrying out the work of the artist, for ‘in painting it is soul which speaks to soul, and not science to science’. Generally photographs were excluded from the fine art sections of exhibitions and tended not to be shown alongside paintings. At the Universal Expositon of 1855, the photographers, many of whom had trained as artists, were represented in one of the Halls of Industry rather than in the Palace of Fine Arts. This was a defeat in the battle for artistic recognition which was to rage for many years to come.

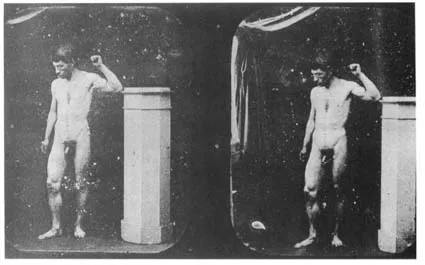

Some artists regarded photography as a means of bringing about radical adjustments of their aims or techniques, and accepted it as a useful and apparently objective demonstration of nourishing truths. While the photographic image served as a means of questioning long-standing assumptions and convictions, it also proved to be a useful way of looking at existing subjects, rather than a means of exploring changes in the form and techniques of art and the chosen subject matter. The fact that many photographers had trained as artists or worked in close association with them ensured that they were familiar with artistic conventions and sought to replicate them in photography. This closeness of the working relationship between artist and photographer is indicated by Pierre Charles Simart’s side view study of a model who is posed in an artist’s studio. To the right is a canvas painted in the classical tradition on which can be seen a pointing child. The model, placed in an apparently stilted pose, necessary because of the length of the exposure, is far from the ideal body type, indicating that it was not the character or personality of the model which principally concerned the artist or the photographer, but rather the objective gaze of the mechanical process.

While many artists responded positively and

3 Anon, Standing Male Nude, c.1860. Daguerreotype, Paris.

creatively to the useful insights of the photographic image, this acceptance closely followed convention and limited what the photographer was encouraged to produce. More often than not photographers set out to re-create classical poses, particularly of such famous and respected artists as Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci. Guglielmo Marconi, who was working in Paris from around 1855 to 1870, made many nude studies for artists. Adam (c.1860–70) [2], a...