Chapter 1

The challenge

In the field of education, one of the most enduring messages is that “everything seems to work”. It is hard to find teachers who say they are “below average” teachers, and everyone (parent, politician, school leader) has a reason why their particular view about teaching or school innovation is likely to be successful. Indeed, rhetoric and game-play about teaching and learning seems to justify “everything goes”. We acknowledge that teachers teach differently from each other; we respect this difference and even enshrine it in terms like “teaching style” and “professional independence”. This often translates as “I'll leave you alone, if you leave me alone to teach my way.” While teachers talk to their colleagues about curriculum, assessment, children, and lack of time and resources, they rarely talk about their teaching, preferring to believe that they may teach differently (which is acceptable provided they do not question one another's right to teach in their particular ways). We pass laws that are more about structural concerns than about teaching concerns: such as class size, school choice, and social promotion, as if these are clear winners among the top-ranking influences on student learning. We make school-based decisions about ability grouping, detracking or streaming, and social promotion, again appealing to claims about influences on achievement. For most teachers, however, teaching is a private matter; it occurs behind a closed classroom door, and it is rarely questioned or challenged. We seem to believe that every teacher's stories about success are sufficient justification for leaving them alone. We will see throughout this book that there is a good reason for acknowledging that most teachers can demonstrate such success. Short of unethical behaviors, and gross incompetence, there is much support for the “everything goes” approach. However herein lies a major problem.

It is the case that we reinvent schooling every year. Despite any successes we may have had with this year's cohort of students, teachers have to start again next year with a brand new cohort. The greatest change that most students experience is the level of competence of the teacher, as the school and their peers typically are “similar” to what they would have experienced the previous year. It is surely easy to see how it is tempting for teachers to re-do the successes of the previous year, to judge students in terms of last year's cohort, and to insist on an orderly progression through that which has worked before. It is required of teachers, however, that they re-invent their passion in their teaching; they must identify and accommodate the differences brought with each new cohort of students, react to the learning as it occurs (every moment of learning is different), and treat the current cohort of students as if it is the first time that the teacher has taught a class—as it is for the students with this teacher and this curricula.

As will be argued throughout this book, the act of teaching reaches its epitome of success after the lesson has been structured, after the content has been delivered, and after the classroom has been organized. The art of teaching, and its major successes, relate to “what happens next”—the manner in which the teacher reacts to how the student interprets, accommodates, rejects, and/or reinvents the content and skills, how the student relates and applies the content to other tasks, and how the student reacts in light of success and failure apropos the content and methods that the teacher has taught. Learning is spontaneous, individualistic, and often earned through effort. It is a timeworn, slow and gradual, fits-and-starts kind of process, which can have a flow of its own, but requires passion, patience, and attention to detail (from the teacher and student).

So much evidence

The research literature is rich in recommendations as to what teachers and schools should do. Carpenter (2000), for example, counted 361 “good ideas” published in the previous ten years of Phi Delta Kappan (e.g., Hunter method, assertive discipline, Goals 2000, TQM, portfolio assessment, essential schools, block scheduling, detracking, character education). He concluded that these good ideas have produced very limited gains, if any. Similarly, Kozol (2005, p. 193) noted that there have been “galaxies of faded names and optimistic claims,” such as “Focus Schools”, “Accelerated Schools”, “Blue Ribbon Schools”, “Exemplary Schools”, “Pilot Schools”, “Model Schools”, “Quality Schools”, “Magnet Schools”, and “Cluster Schools”—all claiming they are better and different, with little evidence of either. The research evidence relating to “what works” is burgeoning, even groaning, under a weight of such “try me” ideas. Most are justified by great stories about lighthouse schools, inspiring principals and inspiring change agents, and tales of wonderful work produced by happy children with contented parents and doting teachers. According to noted change-theory expert, Michael Fullan, one of the most critical problems our schools face is “not resistance to innovation, but the fragmentation, overload, and incoherence resulting from the uncritical and uncoordinated acceptance of too many different innovations (Fullan & Stiegelbauer, 1991, p. 197). Richard Elmore (1996) has long argued that education suffers not so much from an inadequate supply of good programs as from a lack of demand for good programs—and instead we so often supply yet another program rather than nurture demand for good programs.

There is so much known about what makes a difference in the classroom. A glance at the journals on the shelves of most libraries, and on web pages, would indicate that the state of knowledge in the discipline of education is healthy. The worldwide picture certainly is one of plenty; we could have a library solely consisting of handbooks about teaching, most of which cannot be held in the hand. Most countries have been through many waves of reform, including new curricula, new methods of accountability, reviews of teacher education, professional development programs, charter schools, vouchers, and management models. We have blamed the parents, the teachers, the classrooms, the resources, the textbooks, the principals, and even the students. Listing all the problems and all the suggested remedies could fill this book many times over.

There are thousands of studies promulgating claims that this method works or that innovation works. We have a rich educational research base, but rarely is it used by teachers, and rarely does it lead to policy changes that affect the nature of teaching. It may be that the research is written in a non-engaging style for teachers, or maybe when research is presented to teachers it is done in a manner that fails to acknowledge that teachers come to research with strong theories of their own about what works (for them). Further, teachers are often very “context specific”, as the art for many of them is to modify programs to fit their particular students and teaching methods—and this translation is rarely acknowledged.

How can there be so many published articles, so many reports providing directions, so many professional development sessions advocating this or that method, so many parents and politicians inventing new and better answers, while classrooms are hardly different from 200 years ago (Tyack & Cuban, 1995)? Why does this bounty of research have such little impact? One possible reason is the past difficulties associated with summarizing and comparing all the diverse types of evidence about what works in classrooms. In the 1970s there was a major change in the manner that we reviewed the research literature. This approach offered a way to tame the massive amount of research evidence so that it could offer useful information for teachers. The predominant method had always been to write a synthesis of many published studies in the form of an integrated literature review. However in 1976 Gene Glass introduced the notion of meta-analysis—whereby the effects in each study, where appropriate, are converted to a common measure (an effect size), such that the overall effects could be quantified, interpreted, and compared, and the various moderators of this overall effect could be uncovered and followed up in more detail. Chapter 2 will outline this method in more detail. This method soon became popular and by the mid 1980s more than 100 meta-analyses in education were available. This book is based on a synthesis (a method referred to by some as meta-meta-analysis) of more than 800 meta-analyses about influences on learning that have now been completed, including many recent ones. It will develop a method such that the various innovations in these meta-analyses can be ranked from very positive to very negative effects on student achievement. It demonstrates that the reason teachers can so readily convince each other that they are having success with their particular approach is because the reference point in their arguments is misplaced. Most importantly, it aims to derive some underlying principles about why some innovations are more successful than others in influencing student achievement.

An explanatory story, not a “what works” recipe

The aim is to provide more than a litany of “what works”, as too often such lists provide yet another set of recommendations devoid of underlying theory and messages, they tend to not take into account any moderators or the “busy bustling business” of classrooms, and often they appeal to claims about “common sense”. If common sense is the litmus test then everything could be claimed to work, and maybe therein lies the problems with teaching. As Glass (1987) so eloquently argued when the first What Works: Politics and research was released, such appeals to common sense can mean that there is no need for more research dollars. Such claims can ignore the realities of classroom life, and they too often mistake correlates for causes. Michael Scriven (1971; 1975; 2002) has long written about mistaking correlates of learning with causes. His claim is that various correlates of school outcomes, say the use of advance organizers, the maintenance of eye contact, or high time on task, should not be confused with good teaching. While these may indeed be correlates of learning, it is still the case that good teaching may include none of these attributes. It may be that increasing these behaviors in some teachers also leads to a decline in other attributes (e.g., caring and respect for students). Correlates, therefore, are not to be confused with the causes.

For example, one of the major results presented in this book relates to increasing the amount of feedback because it is an important correlate of student achievement. However, one should not immediately start providing more feedback and then await the magical increases in achievement. As will be seen below, increasing the amount of feedback in order to have a positive effect on student achievement requires a change in the conception of what it means to be a teacher; it is the feedback to the teacher about what students can and cannot do that is more powerful than feedback to the student, and it necessitates a different way of interacting and respecting students (but more on this later). It would be an incorrect interpretation of the power of feedback if a teacher were to encourage students to provide more feedback. As Nuthall (2007) has shown, 80% of feedback a student receives about his or her work in elementary (primary) school is from other students. But 80% of this student-provided feedback is incorrect! It is important to be concerned about the climate of the classroom before increasing the amount of feedback (to the student or teacher) because it is critical to ensure that “errors” are welcomed, as they are key levers for enhancing learning. It is critical to have appropriately challenging goals as then the amount and directedness of feedback is maximized. Simply applying a recipe (e.g., “providing more feedback”) will not work in our busy, multifaceted, culturally invested, and changing classrooms.

The wars as to what counts as evidence for causation are raging as never before. Some have argued that the only legitimate support for causal claims can come from randomized control trials (RCTs, i.e., trials in which subjects are allocated to an experimental or a control group according to a strictly random procedure). There are few such studies among the many outlined in this book, although it could be claimed that there are many “evidence-informed” arguments in this book. While the use of randomized control trials is a powerful method, Scriven (2005) has argued that a higher gold standard relates to studies that are capable of establishing conclusions “beyond reasonable doubt”. Throughout this book, many correlates will be presented, as most meta-analyses seek such correlates of enhanced student achievement. A major aim is to weave a story from these data that has some convincing power and some coherence, although there is no claim to make these “beyond reasonable doubt”. Providing explanations is sometimes more difficult than identifying causal effects.

Most of these claims about design and RCTs are part of the move towards evidence-based decision making, and the current debate about influences on student learning is dominated by discussion of the need for “evidence”. Evidence-based this and that are the buzz words, but while we collect evidence, teachers go on teaching. The history of teaching over the past 200 years has attested the enduring focus of teachers on notions of “what works” despite the number of solutions urging teachers to move in a different direction. Such “what works” notions rarely have high levels of explanatory power. The model I will present in Chapter 3 may well be speculative, but it aims to provide high levels of explanation for the many influences on student achievement as well as offer a platform to compare these influences in a meaningful way. And while I must emphasize that these ideas are clearly speculative, there is both solace and promise in the following quotation from Popper:

Bold ideas, unjustified anticipations, and speculative thought, are our only means for interpreting nature: our only organon, our only instrument, for grasping her. And we must hazard them to win our prize. Those among us who are unwilling to expose their ideas to the hazard of refutation do not take part in the scientific game.

(Popper, K. R., 1968, p. 280)

While we collect evidence, teachers go on teaching

As already noted, the practice of teaching has changed little over the past century. The “grammar” of schooling, in Tyack and Cuban's (1995) terms, has remained constant: the age-grading of students, division of knowledge into separate subjects, and the self-contained classroom with one teacher. Many innovations have been variously “welcomed, improved, deflected, co-opted, modified, and sabotaged” (p. 7), and schools have developed rules and cultures to control the way people behave when in them. Most of us have been “in school” and thus know what a “real school” is and should be. The grammar of schooling has persisted partly because it enables teachers to discharge their duties in a predictable fashion, cope with the everyday tasks that others expect of them, and provide much predictability to all who encounter schools.

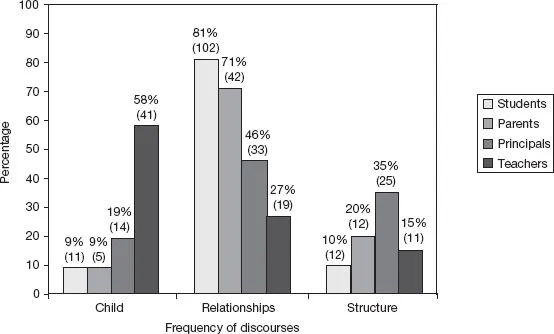

One of the “grammars of schooling” is that students are to be made responsible for their learning. This can easily turn into a conception that some students are deficient in their desire for, and achievements from teaching. As Russell Bishop and his colleagues have demonstrated, such deficit thinking is particularly a problem when teachers are involved with minority students (e.g., Bishop, Berryman, & Richardson, 2002). From their interviews, they illustrated that the influences on Māori students’ educational achievement differed for each of parents, students, principals, and teachers (Figure 1.1). Students, parents, and principals see the relationships between teachers and students as having the greatest influence on Māori students’ educational achievement. In contrast, teachers identify the main influences on Māori students’ educational achievement as being Māori students themselves, their homes and/or the structure of the schools. Teachers engage in the discourse of the child and their home by pathologising Māori students’ lived experiences and by explaining their lack of educational achievement in deficit terms. My colleague Alison Jones calls this type of thinking a “discourse of disadvantage” (Jones & Jacka, 1995). They do not see themselves as the agents of influence, see very few solutions, and see very little that they can do to solve the problems.

Figure 1.1 Percentage of responses as to the claimed influences on student learning by students, parents, principals, and teachers

From their extensive classroom observations, analyses of achievement results, and working with teachers of minority students, Bishop et al. have devised a model of teaching Māori students based on caring for all students, and the primacy of the act of teaching. The major features of Bishop's model include the creation of a visible, appropriate context for learning such that the student's culture is involved in a process of co-learning, which involves the negotiation of learning contexts and content. The teacher provides supportive feedback and helps students to learn by acknowledging and using the students’ prior knowledge and experiences, and monitoring to check if students know what is being taught, what is to be learnt, or what is to be produced. It involves the teacher teaching the students something, instructing them how to produce something, and giving them instructions as to the processes of learning. This is a high level of teaching activity, indeed.

Concluding comments

This introduction has highlighted the amazing facility of those in the education business to invent solutions and see evidence for their pet theories and for their current actions. Everything seems to work in the improvement of student achievement. There are so many solutions and most have some form of evidence for their continuation. Teachers can thus find some support to justify almost all their actions—even though the variability about what works is enormous. Indeed, we have created a profession based on the principle of “just leave me alone as I have evidence that what I do enhances learning and achievement”.

One aim of this book is to develop an explanatory story about the key influences on student learning—it is certainly not to build another “what works” recipe. The major part of this story relates to the power of directed teaching, enhancing what happens next (through feedback and monitoring) to inform the teacher about the success or failure of their teaching, and to provide a method to evaluate the relative efficacy of different influences that teachers use.

It is important from the start to note at least two critical codicils. Of course, there are many outcomes of schooling, such as attitudes, physical outcomes, belongingness, respect, citizenship, and the love of learning. This book focuses on student achievement, and that is a limitation of this review. Second, most of the successful effects come from innovations, and these effects from innovations may not be the same as the effects of teachers in regular classrooms—the mere involvement in asking questions about the effectiveness of any innovation may lead to an inflation of the effects. This matter will be discussed in more detail in the concluding chapter, w...