- 372 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Cell Movements vividly describes how complex movements can arise from the properties and behaviors of biological molecules. This second edition is updated throughout with recent advances in the field and has a completely revised and redrawn artwork program. The text is suitable for advanced undergraduates as well as for professionals wishing for an overview of this field.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cell Movements by Dennis Bray in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

Cell Movements in the Light Microscope

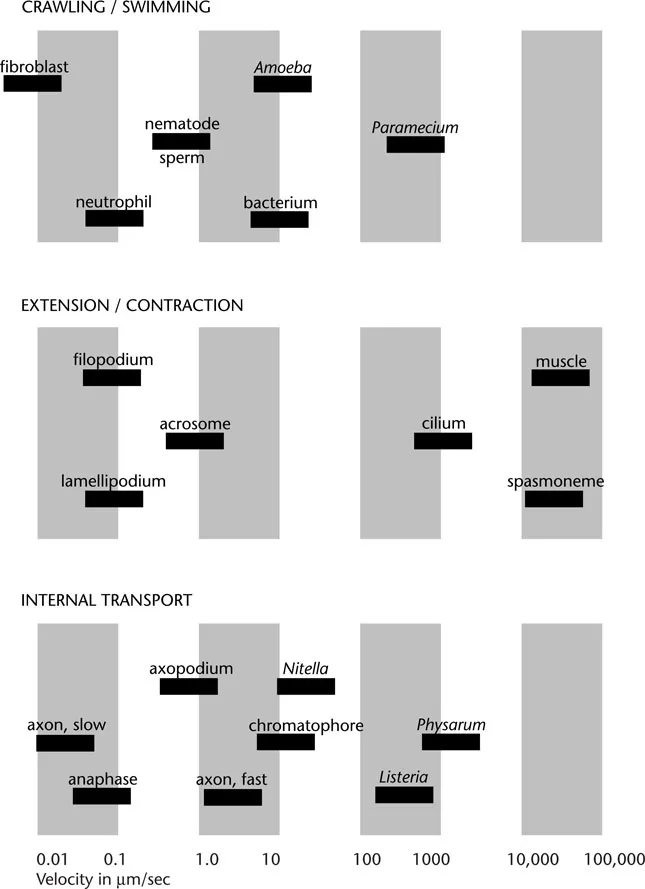

Velocities of some of the cell movements described in the text.

CHAPTER

1

1

Cell Swimming

The first cells ever seen were swimming. When Anthony van Leeuwenhoek, in 1674, brought the glass bead that served him as a primitive microscope close to a drop of water taken from a pool close to his home in Delft, he was astounded to observe it full of minute particles darting here and there. Later he wrote: “… the motion of these animalcules in the water was so swift and various, upwards, downwards and round about, that ‘twas wonderful to see ….” The organisms he saw were probably ciliated protozoa, each a single cell a few tenths of a millimeter in length, swimming by the agitated, but coordinated motion of thousands of hairlike cilia on their surface. The motion of such cells is so obviously directed and purposeful that van Leeuwenhoek knew it could only come from some living creature and not specks of inanimate matter.

Today, with the power and convenience of modern microscopes, we can visualize in rich detail the abundant variety of living cells, each capable of independent, directed motion through water. Sperm cells swim with a characteristic wriggling motion due to their long whiplike tails, or flagella. They often travel large distances to find an egg of the same species to fertilize, especially in aquatic species such as sea urchins. A huge menagerie of different kinds of protozoa exists including the ciliates seen by van Leeuwenhoek. Many of these swim with cilia and/or flagella, searching endlessly for food or for a mate. Even minute bacteria, less than 2 μm long, are capable of moving rapidly through water with a fishlike undulating motion.

How do cells swim, and why? These questions, in various forms and at different levels of enquiry, reoccur throughout this book. In this first chapter, we start by presenting information that is visible in the light microscope, surveying the types of cells that swim and their means of propulsion. We begin by discussing some of the special problems encountered by cells traveling through water because of their minute size.

A cell suspended in water moves passively by diffusion

Because cells are so small, they encounter different physical problems when moving through water than fish or other aquatic animals. The progress of a cell through water is dominated by the viscosity of its environment; inertia, which carries a salmon or an otter forward, plays a negligible part. As for a human swimmer in a bath of honey, a cell moves through water by using a rowing or swimming action in which viscous resistance to the backward stroke is greater than viscous resistance to the forward stroke. It follows from the principle of action and reaction that swimming cells continually push backward against the surrounding water. Usually, this is accomplished by the repetitive beating of minute surface appendages. We will see below that these appendages, called cilia and flagella, encounter greater viscous resistance when they move backward than when they move forward.

Even without cilia and flagella, however, a cell suspended in water moves passively by diffusion. Like any other particle of similar size, a cell in water is pushed first one way and then the other by the thermal motion of surrounding molecules. Since chaotic thermal motion is an ever-present factor for all objects in solution, including objects within the cytoplasm as well as cells themselves, it is useful here to summarize its physical basis.

The speed of the cell undergoing such Brownian movements is directly related to its size. The average kinetic energy of any molecular or small particle suspended in liquid is given by kT/2, where k is the Boltzmann constant and T is the absolute temperature.1 The instantaneous velocity of such a particle will change frequently as it bumps into another molecule or particle, but its average can be calculated by relating the average energy, as expressed above with temperature, and the equation for kinetic energy of any moving body: MV2/2, where M is the mass (kg) and ν its linear velocity (m/sec) in any direction. Equating these two expressions of energy, we find:

Using this simple equation we can calculate that at room temperature the instantaneous speed of a protein molecule will be about 10 m/sec, whereas for a cell the size of a bacterium it will be of the order of 1 mm/sec.

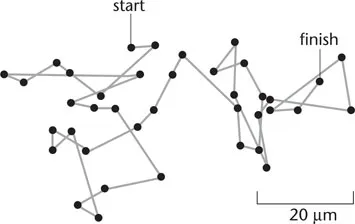

Neither a molecule nor a cell will travel at this speed very far before it bumps into a water molecule and changes both its direction and speed. The continual bombardment by surrounding molecules means that a cell undergoes a random walk, wandering over an ever longer and more tortuous path. In Figure 1-1, for example, the positions of a particle about 1 μm in diameter suspended in water is shown every 30 seconds. The trace of this particle is marked by a succession of straight lines, but if the measurements had been made at intervals of one second instead of 30 seconds, then each straight line segment in the figure would have to be replaced by a series of 30 smaller segments in a path just as tortuous as the one shown … and so on, at smaller and smaller dimensions. In fact, it can be calculated that in order to measure the true steps of such a particle, one would have to take measurements at less than a microsecond and over distances less than a nanometer (10–9 m).

Brownian movements are random and we cannot predict precisely where the cell will be at any time. But if many cells were to start out from the same point, then we would be able to say what their average distribution would be at different times (equivalently, we could calculate the probability that any one cell would be in a particular location after a given time).

Figure 1-1 Brownian motion. The paths followed by a minute particles as seen under a microscope. Positions of the particles were measured every 30 seconds and joined by straight lines. If the particles had been examined at higher magnification or measured at shorter intervals of time, the paths would have been far more complex than indicated here, since the true trajectory of a particle changes direction on a time scale of microseconds. (Based on Perrin, 1909.)

Diffusion is ineffective over large distances

The distribution of diffusing particles (or cells, or molecules) in solution conforms to precisely defined spatial and temporal laws. These were first expressed mathematically in 1855 by the physiologist Adolf Fick, who adopted a set of differential equations already in use for the diffusive spread of heat in a solid. Fick’s first law of diffusion says that the rate of diffusion of particles from one point to another is proportional to the difference in concentration of the particles between the two points. That is

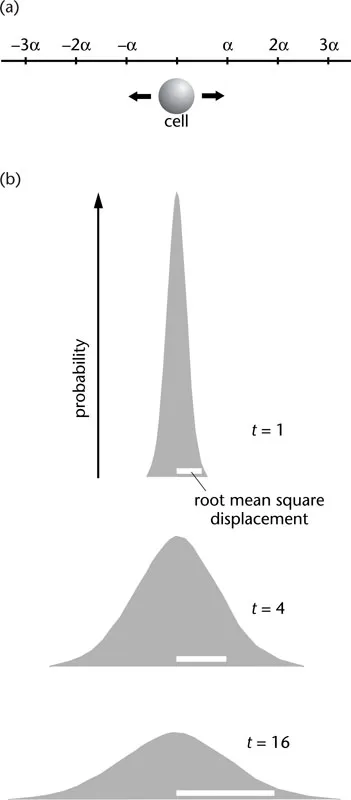

Figure 1-2 One-dimensional random walk. (a) At each step the cell has an equal chance of moving to the left or the right a distance α. If the distance of the cell from its starting point after n steps is rn then

squaring this gives

and

If we average these two values of rn2 over a large population of similar cells, the terms ± 2αrn–1 cancel (because steps to the left and right are equal in number), giving the mean square displacement

Since all cells start at point zero,

and so on. In other words, the mean square displacement |rn2| increases linearly with the number of steps, n, and hence with the elapsed time. That is

(b) Spreading of a population of cells undergoing a onedimensional walk. Probability distributions at three times after commencing the random walk described in the text. The root mean square displacement (white bars) increases as the square root of time.

where Jx is the flux of particles (the number passing through a window of unit area in unit time); N is the number of particles per unit volume, x is the distance, so is the concentration gradient. The constant D, known as the diffusion constant, depends on the size of the particle, its shape and other factors.

Fick’s law says nothing about the origins of the force driving the molecules. There is, however, an alternative description of diffusion that is more closely tied to the physical reality of the situation. This description, given by Albert Einstein in 1905, attributes diffusion to the thermal (Brownian) motions of the particles that cause them to undergo the random walk described above.

To illustrate this second approach to diffusion, consider a population of particles constrained to move along a linear track (Figure 1-2a). All of the particles start at the same initial point and then take individually random steps either to the right or to the left. As time passes and more steps are taken, the particles will on average travel farther and farther from their starting point. However, the probability of a step to the right is equal to that of a step to the left, so on average the particles go nowhere! The result of many such steps by many particles is, on average, a bellshaped distribution that becomes broader with time (Figure 1-2b).

A convenient measure of this spreading tendency is the mean square displacement of the particles |r2|, which is always positive, a linear function of the duration of the random walk. That is

or, as it is usually written,

where t is the time elapsed and D is the diffusion constant already mentioned. In one dimension |r2| = 2 Dt as shown; in two dimensions |r2| = 4 Dt and in three dimensions |r2| = 6 Dt. Typical values of D, together with the average time taken to diffuse specific distances, are given in Table 1-1 for molecules, organelles and cells.

Table 1-1 Diffusion times in water

Diffusion coefficient cm2/sec | 1 μm | Typical time taken to diffuse indicated distance 10 μm | 1 mm | |

small molecule | 5 × 10–6 | 1 msec | 0.1 sec | 15 min |

protein molecule | 5 × 10–7 | 10 msec | 1 sec | 3 hr |

virus particle | 5 × 10–8 | 0.1 sec | 10 sec | 1 day |

bacterial cell | 5 × 10–9 | 1 sec | 100 sec | 10 days |

animal cell | 5 × 10–10 | 10 sec | 20 min | 100 days |

Approximate values are given solely to indicate the magnitudes involved. The times are calculated for three-dimensional diff...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- PART 1 Cell Movements in the Light Microscope

- PART 2 Molecular Basis of Cell Movements

- PART 3 Integration of Cell Movements

- Glossary

- Index