This first chapter provides an overview and understanding of core tourism concepts and the importance of their definition for evaluating impacts and change.

Introduction

The impacts of tourism are receiving more public attention than ever before. Issues in the media as varied as climate change, coastal urbanization, demand for water by resorts and golf courses, the loss of agricultural land for development, the spread of exotic pests and diseases (see Case 1.1), economic and industrial change, fossil fuel consumption, increased cost of energy, changes in housing and communities, and sex tourism have all focused on the more controversial roles of tourism in contemporary society. Prince Philip in a royal tour of Slovenia in 2008 reportedly branded tourism ‘national prostitution’, going on to say ‘We don’t need any more tourists. They ruin cities’ (Royal Watch News 2008). However, to what extent is tourism ‘guilty’ of these? And how are we to understand them?

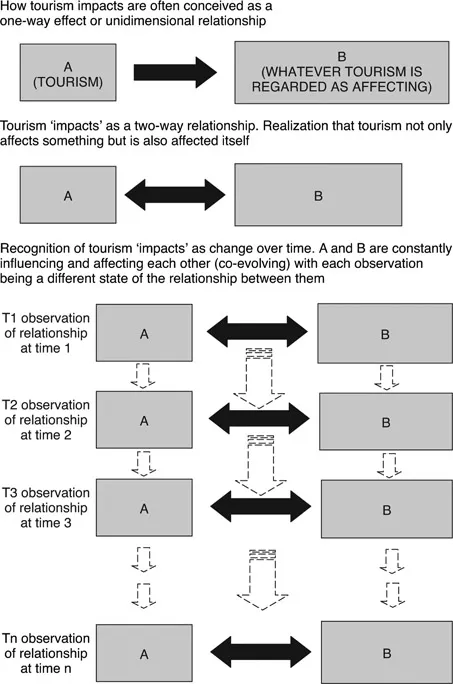

This book seeks to address such issues and provide students of tourism with an improved understanding of what the effects of tourism might be, how they can be evaluated and how they can be managed. One of the first concepts we wish to address is that of an impact. The way the term is used implies that tourism has an effect on something, be it a place, person, environment or economy. The term also often suggests that this is a unidimensional or ‘one-way’ effect (Figure 1.1). However, tourism impacts are very rarely, if ever, a one-way relationship. In fact, tourism both affects people and things and, in turn, is affected by them. Furthermore, tourism impacts are rarely, if ever, just an issue of environmental, social, economic or political impact. Instead, at least two, if not all of these dimensions emerge to varying degrees when the effects of tourism activities are

Figure 1.1 The nature of impacts.

being studied. This is because tourism affects the physical environment; it affects people, communities and the broader social environment; it has economic effects; and it can be very political, especially with respect to how places both attract and manage tourism (see Cases 1.2 and 1.4 as examples of this). Therefore, management of the impacts of tourism requires an integrated approach that aims to bring these various dimensions of tourism together.

The term tourism impacts is usually used as a kind of shorthand – and a poor one at that – to describe changes in the state of something related to tourism over time. A term such as tourism-related change would be a much better way of describing what people mean when they say tourism impacts, but unfortunately people tend to be lazy, and apart from discussions between a few tourism researchers the term impact is the one in common use, and the one we are stuck with! Therefore, throughout this book when we use the term impact please note that we are also using it as shorthand for change. In fact, this concept of impact as ‘changes in a given state over time’ is one of the key messages of this book, which starts to provide new insights into the role of tourism in cultural, economic and environmental change.

Before going into greater detail on how impacts can be understood, assessed and managed, this first chapter will provide some context with respect to the core concepts of tourism, illustrating why the nature of tourism makes it inherently difficult to monitor and manage.

Case 1.1: Ecotourism and the introduction of pests and disease

Ecotourism is generally defined as tourism that is friendly towards the environment and local people, and helps conservation. However, tourism is increasingly being connected to the introduction of exotic pests and diseases that are endangering some of the very species and environments that ecotourism is trying to protect (see also Chapter 5). This case study demonstrates the way tourism, and for that matter any human intervention in the natural environment, can have unforeseeable impacts.

Great ape tourism, to see gorillas and orangutans in their native habitats, is an extremely popular form of ecotourism to travellers who are willing to spend very high prices for the experience. Tens of thousands of visitors each year pay to see the great apes, which are only experienced by most people in developed countries either in a zoo or on television programmes such as Animal Planet. However, scientists became alarmed following the publication of evidence that great apes are dying from respiratory viruses directly transmitted to them by humans. They fear that existing safety measures to protect the apes, who are genetically very similar to humans and therefore subject to many of the same diseases and illnesses, do not go far enough and are calling for stricter precautions, including the mandatory wearing of face masks for all who come into relatively close contact with gorillas, orangutans and chimpanzees (Köndgen et al. 2008).

Photo 1.1 An orangutan in a rehabilitation enclosure in Balikpapan in Indonesia on the island of Borneo. Many of these orangutans were kept as pets when small, but became too strong to keep as adults. Rehabilitation centres work to prepare them to live in the wild. Most of these centres are open to tourists who help fund their efforts through entrance fees and longer-term donation programmes. (Photo by Alan A. Lew)

Their concern follows the first evidence that chimpanzees in the Ivory Coast (Côte d’Ivoire), in West Africa, died from HRSV (human respiratory syncytial virus) and HMPV (human metapneumovirus) during outbreaks at the Taï chimpanzee research station. Viral strains sampled from chimpanzees were closely related to strains circulating in contemporaneous, worldwide human epidemics. The study used a multidisciplinary approach involving behavioural ecology, veterinary medicine, virology and population biology to track human disease introduction into two chimpanzee communities in the country’s Taï National Park, where researchers first began to habituate chimpanzees to human presence in 1982 (Max Planck Society 2008).

Twenty-four years of mortality data from observed chimpanzees reveal that such respiratory outbreaks could have been occurring from research activities for a much longer time than had been known. At the same time, survey data also show that the presence of researchers has had a strong positive effect in suppressing poaching around the research site (Köndgen et al. 2008).

The findings pose a major problem for those protecting the declining populations of gorillas in Uganda, Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo, now numbering less than 650, as well as orangutans on Borneo and Sumatra in Indonesia, thought to number around 15,000. The tourist dollar is essential for protecting the endangered apes from poachers and funds vital work aimed at halting their decline from commercial hunting and habitat loss. However, the new research illustrates the challenge of maximizing the benefit of research and tourism to great apes while minimizing the negative side effects.

In an Observer newspaper report Dr Jo Setchell, a primatologist at Durham University in the UK and member of the Primate Society of Great Britain, was quoted as backing the calls for more stringent precautions, saying:

It is very concerning. It is something that has been raised before, but this is the first report that really demonstrates concretely that these viruses are transmitted by humans… I think the masks are essential… One of the major problems is if you go on a fairly short holiday to, say, Uganda, and you have paid a lot for your permit, if you have a slight cold many people will not forgo that money. They’ll take medication to hide their symptoms – because it’s a big tourist experience, they have waited a long time for it, and it is very expensive.

(in Davies 2008)

Source: Max Planck Society Press Release: http://www.mpg.de/english/illustrationsDocumentation/documentation/pressReleases/2008/pressRelease 20080125/index.html

Defining tourism

Definitions are fundamental to any subject. Each area or domain of research has, as one of its first tasks, the identification of the things that comprise the foci of study. In tourism studies we are faced with four interrelated concepts – tourism, tourist, tourism industry and tourism resources – which provide the core, in one form or another, for the subject that we study (Hall 2005a; Hall and Page 2006). Such issues are not abstract. They are fundamental to being able to understand impacts and how to manage them, no matter how wearisome or academic it might seem. For how can you possibly assess the impacts of tourism unless you can define what tourism is? How can you manage or regulate tourism unless you can define what it is you are trying to regulate?

Tourism is a slippery (see MacNab 1985; Eden 2000; Wincott 2003, for other slippery concepts) and a fuzzy concept (Markusen 1999). It is relatively easy to visualize yet difficult to define with precision because it changes meaning depending on the context of its analysis, purpose and use.

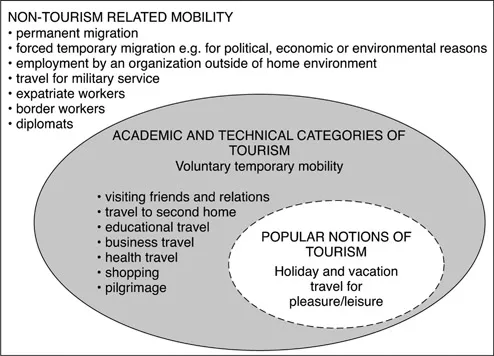

Tourism is, therefore, a concept that, while initially looking very easy to define, is actually quite complex, with a substantial literature written specifically on the issue of definition (see Smith 2004, 2007). Much of the problem with considering the concept of tourism is that most people think of tourism in terms of leisure travel or being on a holiday or vacation. However, the concept is much wider than that (Figure 1.2) and can be interpreted from a number of academic or technical perspectives.

In distinguishing tourism from other forms of human movement several ideas become significant. First, tourism is voluntary and does not include the forced movement of people for political or environmental reasons, that is tourists are not refugees. In fact, the more impoverished someone is the less likely it is that they travel for leisure; and if they have to travel across a border, they are less likely to be welcomed. Rich people, by contrast, are usually welcomed and given far more privileges in crossing international borders than are the poor.

Second, tourism can be distinguished from migration because a tourist is making a return trip while the migrant is moving permanently from what was their home environment. While migration represents a form of voluntary one-way human mobility, tourism can be referred to as a type of voluntary return mobility.

Third, the distinction between tourism and migration sometimes becomes blurred because some people travel away from their home environment for a long time (such as on a gap year or ‘overseas experience’, although they are still intending to return) or because some are working, if only temporarily, in another country. In these types of situations, time (how long they are away from their normal or permanent place of residence) and distance (how far they have travelled or whether they have crossed jurisdictional borders) become determining factors in defining tourism and migration.

Based on these factors tourism includes those forms of voluntary travel in which people travel from their usual home environment to another location and then

Figure 1.2 Popular and academic conceptions of tourism.

return in a manner that is shorter in time and longer in distance than non-tourism forms of similar human mobility (Figure 1.3). Using this broad definition of tourism, and given academic, statistical and research consideration...