Chapter 1

The global ethical trilemma

Ecological economics arose from the need to confront a challenge that humankind had not experienced before. We are now living in a world economy the destiny of which we all share. While producing prosperity on a scale never conceived of in earlier generations, we have been forced to admit that threats to the life-supporting ecological systems are accumulating at an unprecedented speed. The clash between the economic and the ecological systems has become an elementary fact, not only locally but globally. The need for an approach that can tackle this dilemma in a straightforward way is obvious.

Looking at the ecological problems from a global perspective we cannot abstract from the glaring inequalities between peoples. Some earn and consume much more than others; the question of how to tackle the ecological challenges therefore has to be linked to the question of how to achieve a more just distribution of the economic opportunities. Ecological economics has to place global equity on its agenda – a task that makes it even more demanding, scientifically as well as politically.

The need for integrating justice into the analysis of the interaction between economy and ecology was obvious soon after the publication of the path-breaking report Limits to Growth (Meadows et al. 1972). The message of this Club of Rome publication was that if humankind continued to expand its population and consumption as it had until then it was heading for grave ecological catastrophes in the twenty-first century. There were physical limits to growth and the only way to avoid a catastrophic future was through the reduction of population growth and the stabilization of industrial production. For many this implied not only a stop to population growth in the poor South, but also reducing industrial growth everywhere.

A group of Latin American researchers wrote a counter-report, Catastrophe or New Society? A Latin American World Model (Herrera et al. 1976), arguing that the majority of humankind already was living in a state of misery, and that for them the crisis was already here. Therefore, economic growth had to be speeded up in the South. The inequities of the world could not be maintained while trying to avoid a future catastrophe that would bring the crisis also to the North.

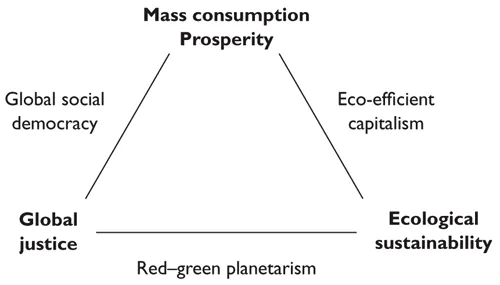

The Latin American world model – also called the Bariloche model – pointed to a global ethical trilemma. There are three goals that most of humankind subscribes to – prosperity, justice and sustainability – but to combine the three goals on the global level is a challenge that is hard to confront. Let us discuss this global ethical trilemma with the help of Figure 1.1.

The corners of the triangle correspond to the three components often included in the definitions of sustainable development: the ecological (sustainability), the economic (prosperity) and the social (justice) dimensions. The difficulty to achieve all three on a global level is an enormous challenge for all who see sustainable development as the central political goal of our age. It is this challenge that makes ecological economics so fascinating.

Let us start by looking at each corner separately. We shall then go into the three sides, each representing an important ideological stance in the world of today.

Prosperity

Let us take a step back to the “Golden Age” of the 1950s and 1960s. The mood of that time was characterized by the belief in economic growth and mass consumption. A most influential book was written by the American economist and political theorist Walt Whitman Rostow. The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto (1960) became a classic text in several fields of social sciences.

According to Rostow’s stage theory the mass consumption society constitutes the end goal of humanity. Through a take off into self-sustained growth each country can start a process of economic growth that will bring it to the final stage – that of a mature mass consumption society. They can become as prosperous, democratic and bored as the United States already had become. When Rostow wrote his book only the USA had achieved this fifth stage – “the age of high mass-consumption.” Western Europe and Japan were on the verge of achieving it, and the Soviet Union was, according to Rostow, engaged in an unhappy love affair with it. This is how he described the mature mass consumption society:

According to the Rostowian worldview it is possible for all nations to achieve the stage of mature mass consumption. Like airplanes one after the other they could take off into self-sustained growth. This they could do through imports of ideas and capital and by taking part in the international division of labor. The rich countries were the natural allies – not obstacles – for the poor in their efforts to develop.

However, in line with the mood of his time, Rostow did not treat problems related to the environment or the limits to growth. For him exports of raw materials were the natural starting point for acquiring the means to develop.

The spirit of that age, which later was called “the Golden Age,” “fordism,” and “the age of oil, cars and mass consumption,” was severely damaged during the 1970s, but still “the American way of life” is a much desired goal all over the world. By means of globalization and new technological advances all nations are striving to enhance their prosperity. Economic growth is still the standard for success globally.

Justice

The quest for justice is shared by all ethical doctrines. However, some doctrines are less inclusive than others. Today, probably for the first time in history, the concern for justice has, however, been extended to all of humankind, not only to those of the same nationality or religion. The human rights declaration adopted by the United Nations in 1948 marks the breakthrough of the quest for global justice, although it still was seen as the duty of every member state to secure these rights to all its citizens. The international community, through a myriad of international organizations, has gradually accepted the role as the defender of universal human rights and justice on a global level.

One way of trying to formulate what justice means is to use the concept of capability – to be or to do what you value – and to link it to sufficiency, universality and sustainability.

Global justice means that the desired level can be achieved everywhere, and that it can be maintained. It therefore has both an international and an intergenerational aspect.

People’s capabilities to live a worthy life depend on society as a whole – institutions, culture, and respect for others. We can even say that today our individual capabilities are formed by a global system – economically, culturally, and ecologically. There may be just societies in a world that is deeply unjust.

Since we live in a world where money can buy almost anything anywhere, the distribution of incomes is one central indicator of how just or unjust the world has become. In the last 200 years the income differences between the continents has grown outrageously. At the beginning of the nineteenth century incomes per capita were three times higher in Western Europe than in Africa. Today the gap between North America and Africa is greater than 20 to 1.

Everyone agrees that we do live in an unequal world. If we take that quintile of the world population that live in the richest countries, and compare their situation to that of the quintile living in the poorest countries, we find the following ratios (Hedenus and Azar 2005):

• Income (compared in terms of market exchange rates – MERs – among the respective currencies) is more than 70 times higher

• Income (compared in terms of purchasing power parity exchange rates) is reckoned as more than 10 times higher

• Consumption of animal food is 7 times higher

• Release of carbon dioxide is 22 times higher

• Consumption of electricity is 35 times higher

• Consumption of paper is 89 times higher.

Since the 1960s the income disparity reckoned in terms of MERs has grown like wildfire; the ratio used to be around 25:1, but is now around 75:1. The corresponding ratio in terms of estimated purchasing power – PPP – has remained more or less constant (around 15:1), but in absolute terms the PPP-gap has increased from $9,200 per capita in 1960 to $23,000 in 2000. Since MERs, rather than purchasing power parities, determine the price competitiveness of nations, they influence the international division of labor. A lot of clothing purchased in the USA is made in Bangladesh and wages in Bangladesh vary between 6 and 18 cents/h; that is you can buy the work of more than 100 Bangladeshis for the cost of one worker in a rich country (Schor 2005b).

The ratios of various kinds of resource–consumption inequalities have tended to diminish, but the absolute differences have been and still are growing. An exception to this general trend is that per capita consumption of animal food has started to decline in the richest countries, while increasing slightly in the poorest ones.

However, we should note that in today’s world, it may well be misleading to reckon merely in the statistically convenient terms of rich and poor nations. Income distribution within many rich countries is becoming more unequal, and the number of rich people in the poorest countries has been growing slightly. The inequality among the world’s individuals is staggering. At the turn of the twenty-first century, the richest 5 percent of people receive one-third of total global income, as much as the poorest 80 percent. While a few poor countries are catching up with the rich world, the differences between the richest and poorest individuals around the globe are huge and growing (Milanovic 2005).

We live in an unequal world.

Ecological sustainability

The term sustainability has its roots in ecology as the ability of an ecosystem to maintain ecological processes, functions, biodiversity, and productivity in the future. To be sustainable, nature’s resources must only be used at a rate at which they can be replenished naturally. There is now clear evidence that humanity is living unsustainably by consuming the Earth’s limited natural resources more rapidly than they are being replaced. Consequently sustainability has come to mean a call for action, for a collective human effort to keep human use of natural resources within the Earth’s finite resource limits.

We will see that there are many definitions and measures of sustainability, but the aim of attaining sustainability has become a fundamental value comparable to liberty or justice.

Every second year the global conservation organization the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) publishes its Living Planet Report. The report contains several measures that indicate the extent to which humankind is overusing nature, threatening the wildlife and causing global inequities. The Living Planet Index reflects the...