The United States, North Vietnam, and South Vietnam each had unique difficulties as the war entered 1968. At the end of 1967, the war had cost the United States over sixteen thousand deaths and over fifty-three thousand wounded since 1960, with the vast majority of those casualties occurring after the American buildup began in 1964–65. South Vietnam had lost over fifty thousand killed and over eighty thousand wounded since the North Vietnamese military effort began in earnest in 1960. PAVN and PLAF forces had lost perhaps as many as 200,000 killed and untold thousands wounded. As pressure mounted in the United States to show progress in the war and in stabilizing the South Vietnamese government, so too did pressure increase in North Vietnam to bring a successful close to the conflict.

The American political and military context

The American war in Vietnam had evolved from a comparatively small advisory effort in the late 1950s to build up South Vietnamese forces and establish stable government in South Vietnam, which had been divided from its northern neighbor since the end of the French Indochina War in 1954, to a major Americanized war effort involving over 480,000 American forces by 1967. As North Vietnam and the NLF became more aggressive in their war for unification in 1963–4, it became more apparent that South Vietnam could not fight on its own. Questions about South Vietnamese military effectiveness, combined with a weak government and enemy attacks directed against American forces and installations, served to convince the Johnson administration in 1965 to begin “Americanizing” the war.

This was not a total war effort like that the United States had mounted against Germany and Japan in World War II. Because of the world geopolitical situation, this war was a limited war, a conflict that was part of the broader Cold War between the United States and its allies and the Communist sphere dominated by the Soviet Union and China. American Cold War strategy dictated that the United States assist South Vietnamese resistance against North Vietnamese aggression. With American prestige at stake, the United States felt compelled to defend smaller, lesser-developed nations against Communist aggression.

President Lyndon Johnson attempted to conduct the war in Vietnam in a manner that did not directly threaten the Soviet Union or China, to avoid a broader general war, and that did not overburden the American economy. Johnson’s ambitious domestic agenda, his Great Society programs, would be jeopardized by a large war in far-away Southeast Asia. Thus, escalation was gradual from 1964 through 1967 and the United States did not invade North Vietnam and resisted calls from the military to conduct sizeable incursions into Laos and Cambodia. The military relied upon the draft to augment the professional force that was fighting in Vietnam, manning the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) in Korea, and deterring a Soviet invasion of Western Europe. To avoid the perception of a larger war, the Johnson administration did not mobilize the reserves, did not institute price controls and rationing in the United States, and generally did not attempt to unify broad support for the war.

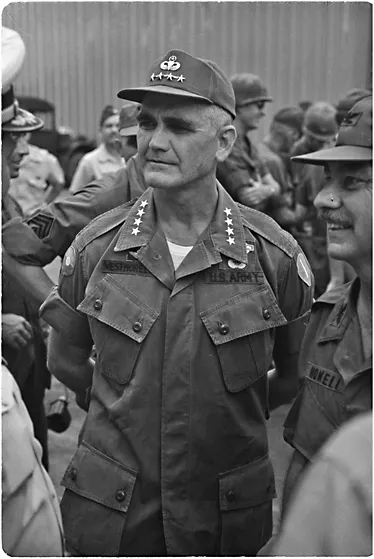

Under the command of General William Westmoreland, Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) adopted a three-pronged strategy as the American role in the conflict increased in 1965 (Figure 1). One part of this approach was a strategy of attrition using tactics that came to be known as “search and destroy.” American and South Vietnamese Army (ARVN) units would patrol the jungles and countryside to make contact with Viet Cong forces, and then call in massive American firepower from either artillery or air assets, or both, to lay a swath of destruction upon enemy positions. Commanders measured success through body counts, literally by counting corpses found on the battlefield. The objective of such a strategy was to kill or injure as many enemy soldiers as possible to make the cost of continuing the war too high, thus breaking the enemy’s will to fight. The other part of the strategy was interdiction to stop the flow of men and material into South Vietnam from North Vietnam and along the Ho Chi Minh Trail through Laos and Cambodia. Massive bombing along the trail and a series of firebases just south of the DMZ along the 17th Parallel that divided North and South Vietnam attempted to stop what became a very sophisticated and efficient logistical system from North Vietnam. The third part of the American approach to the war in Vietnam involved bombing of selected targets in North Vietnam, with the dual hope of hurting the ability of the North Vietnamese to supply its troops and Viet Cong units in the south and coercing North Vietnam to the peace table to guarantee an independent and free South Vietnam.

This military strategy was initiated to support American efforts to establish stable democratic government in South Vietnam, which had made little progress. Creating a stable government that respected the rule of law and

avoided the abyss of corruption, and that could thus establish trust and legitimacy with the Vietnamese people, proved extremely difficult. Pacification programs tried to improve life and sway the rural peasantry from the NLF camp. This campaign of “winning hearts and minds,” as the vernacular at the time called it, was separate from the military campaign, but nonetheless encountered problems of poor administration and corruption. By 1967, reports concluded that the VC still largely controlled the countryside.

Corruption had always existed in South Vietnam, but the problem had been considerably exacerbated by the massive influx of American military and luxury goods into South Vietnam. Stabilizing the South Vietnamese economy, with extensive government corruption and an insurgency war underway in the countryside and American dollars unintentionally competing for preeminence with Vietnamese piasters, was an equally daunting undertaking. Despite a Herculean effort on the part of American military advisors and billions of dollars in equipment and training, the South Vietnamese military also remained questionable as an independent and effective fighting force. In 1965, the Johnson administration concluded that the GVN and its military could not successfully fight the NLF insurgency. Facing limited strategic options, Johnson decided to escalate the American presence and Americanize the war rather than withdraw from South Vietnam completely.

American military operations since beginning the escalation in 1965 had been dramatic but marginally effective. Using ARVN forces to protect the cities allowed Westmoreland to use American Army and Marine units to conduct operations in the countryside, the control of which would in turn allow pacification programs to have their fullest effect. The bombing campaign designed to force North Vietnam to the peace table and stop support of the VC insurgents in the South had been extensive and expensive, but in over two years Operation Rolling Thunder had failed to achieve either objective. Search and destroy operations involving air insertion of American forces, such as Operation Starlite in 1965 and Operation Junction City in February 1967, often succeeded in the short term in stopping PLAF and PAVN movements, but enemy forces frequently returned to the areas weeks later. Ground operations designed to corral PLAF forces in a particular area and destroy them with massive firepower, such as Operation Cedar Falls in January 1967, also had some short-term impact but little lasting effect. Viet Cong units in the Iron Triangle region northwest of Saigon reoccupied many positions evacuated because of Cedar Falls soon after the operation ended. The significant impact such operations did have was to force the PLAF to relocate sanctuaries across the border into Cambodia, which for the United States only threatened to broaden a limited war that American political leaders had hoped to contain in South Vietnam.

Despite inflicting heavy casualties, none of these approaches seemed to be making real progress toward ending the conflict on American terms. PLAF units quickly learned how to minimize casualties from American search and destroy missions, mainly through an uncanny ability to melt back into the forest and jungle through a series of tunnels and well-hidden trails. The interdiction campaign along the DMZ and the Ho Chi Minh Trail had little effect, as the trail’s design allowed for repairs to be made while men and material continued uninterrupted along nearby detour routes. The amount of material transported down the trail from North Vietnam actually had increased year to year through 1968. Bombing was frequently disrupted because of the weather, especially during the rainy season, and much of the trail ran just outside Vietnam along the border with Laos and Cambodia, which further complicated ground and air operations to destroy the trail.

By 1967, the over 100,000 sorties of the air campaign against North Vietnam were no closer to bringing Ho Chi Minh to the peace table than approximately twenty-five thousand sorties flown in 1965. Sophisticated Soviet and Chinese air defense systems made bombing missions even more dangerous, inefficient, and costly, as pilots now had to spend more time against air defense targets rather than on important military, industrial, and logistical targets. More and more American aircraft were shot down over North Vietnam, with dozens of pilots and crew taken prisoner, some being held in North Vietnamese prisoner-of-war camps for more than seven years by the time the American war ended in early 1973.

American casualties and financial costs of the war mounted quickly. The war effort was beginning to have an adverse effect on the American economy, particularly on the value of the dollar. The war was now costing American taxpayers over $2 billion per month, which annually amounted to about 3 percent of the Gross National Product (compared to 12 percent during the Korean War and over 40 percent for World War II). In August 1967, Johnson proposed a 10 percent surcharge on all income tax returns to help offset increasing military expenditures so he could continue his Great Society domestic agenda.

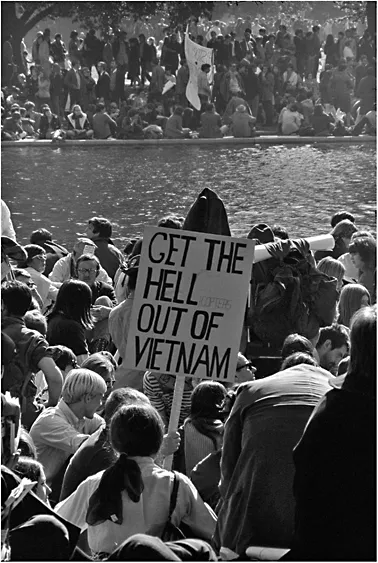

Daily casualty reports appeared in newspapers and nightly on network television news. Draft resistance increased by 1967 and anti-war protests were also on the rise in number and intensity. On October 21, 1967, over 100,000 gathered on the Washington Mall to protest the draft with a march on the Pentagon (Figure 2). Abbie Hoffman and Norman Mailer gave speeches, while Peter, Paul, and Mary sang protest songs from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. Nearly half of the crowd crossed the Potomac River to the Pentagon, where thousands of hippies tried to levitate the building as an exorcism of the evil inside it. Hundreds were arrested, but it was clear to many that whether or not one agreed with the war, an increasingly larger segment of the country was turning against it.

Convinced that the anti-war movement was responsible for his downturn in the polls, Johnson ordered the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to begin surveillance and harassment of anti-war protest leaders and others who questioned his policies. The CIA’s Operation Chaos ultimately created files on over seven thousand Americans involved one way or another with the anti-war movement. Public opinion polls by mid-1967 clearly showed the American people were tiring of the war and concerned about the lack of progress as measured against the increasing cost in casualties and money. In late summer, two-thirds of the American public no longer supported President Johnson’s leadership of the nation, and by early fall, for the first time more Americans than not thought Vietnam was a mistake.

The war seemed to be making little headway and was perhaps even stuck—thus the frequent characterizations of the war as a quagmire or stalemate. Once hawkish senators and congressmen began questioning Johnson’s war policies. General William Westmoreland and the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) proposed plans that would expand the war into Laos and Cambodia, even north of the DMZ into North Vietnam, with an increased total force of 542,000 American troops in country by mid-1968. Westmoreland had become convinced that what analysts called the “cross-over point,” the point at which PAVN and PLAF units could no longer replace losses in the field, was near. The troop increase would provide an overwhelming offensive force that could then wipe out the PLAF in the South and deter PAVN operations south of the DMZ. But Johnson could not afford the domestic economic and political price of calling up the reserves while also increasing monthly draft allotments, and therefore allowed only a fraction of what Westmoreland had requested.

In May 1967, Johnson acceded to Westmoreland’s request to militarize the pacification program. Since the beginning of American involvement in Vietnam, pacification programs had been decentralized and under the operation of numerous agencies, often at cross-purposes. Westmoreland longed to centralize the disorganized programs under the control of MACV. Under the new Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development Support agency (CORDS), pacification became not only centralized, but militarized. Despite the ef...