1

Travel, tourism and carbon management

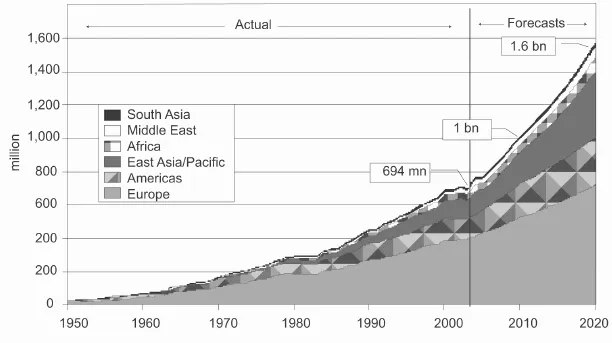

Tourism has grown immensely over the past 60 years. From 1950 to 2005, international arrivals have grown by 6.5 per cent per year, i.e. from an estimated 25 million in 2050 to 806 million in 2005 (Figure 1.1; UN World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) 2001, 2010a). In the following three years to 2008, international arrivals increased by more than 100 million to 920 million. By then, however, the global financial crisis set a stop to the strong growth trend, and arrivals declined by 4 per cent in 2009 to 880 million (estimate, UNWTO 2010b). However, UNWTO (2010b) projects that the world economic system will stabilize and that growth will resume at 3–4 per cent in international tourist arrivals in 2010 to reach 1.6 billion in 2020 (UNWTO 2001).

Domestic tourism has grown even faster, and accounts now for almost 10 times more tourist trips than international tourism (UNWTO-UNEP-WMO 2008). The enormous growth in

global mobility for leisure and business has been going along with high and growing energy use: travel to the destination, staying at the destination, and tourist activities are all energy-intense. As most energy for tourism is derived from fossil fuels, tourism is also a significant contributor to climate change. In the future, with an expected 1.6 billion international tourist arrivals by 2020 (UNWTO 2001), tourism is likely to become an ever more important factor in global warming, particularly in a world seeking to decarbonize. So far, few actors in tourism appear to have been concerned with this. As this book argues, there is thus an urgent need to address energy consumption and associated emissions of GHGs in tourism planning, management, politics and education.

Even though Carbon Management in Tourism is the first book to exclusively deal with emissions from tourism, aspects of climate change mitigation in tourism have been considered in a number of scientific books, including C. Michael Hall and James Higham’s (2005) edited volume Tourism, Recreation, and Climate Change, which covers a wide range of related issues; Stefan Gössling and C. Michael Hall’s (2006) Tourism and Global Environmental Change, another edited volume with an ecosystem-/theme-specific approach; and Susanne Becken and John E. Hay’s (2007) Tourism and Climate Change, which provides a general overview of tourism, adaptation and mitigation, and a very readable introduction to many basics of mitigation.

Moreover, there have been two reports summarizing the knowledge in the field and providing specific advice of how to achieve emission reductions. These are ‘Tourism and Climate Change: responding to global challenges’, published by the UN World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and World Meteorological Organization (WMO) in 2008, as well as ‘Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation in the Tourism Sector: Frameworks, Tools and Practice’, published by UNEP, Oxford University, UNWTO and WMO, also in 2008. ‘Tourism and Climate Change: responding to global challenges’ is still the most comprehensive overview of the two-way relationship of tourism as a sector being affected by climate change as well as contributing to climate change. The report is also highly relevant for this book, because it contains the first detailed assessment of emissions from tourism transport, accommodation and activities (for an earlier rough assessment see Gössling (2002)). UNEP-Oxford University-UNWTO-WMO (2008) contains some theory and examples of tourism businesses that have sought to engage in climate change mitigation. This book seeks to go beyond these reports by summarizing the knowledge in the field in a comprehensive state-of-the-art review, and by providing in-depth case studies illustrating carbon management in practice.

HOW TO READ THIS BOOK

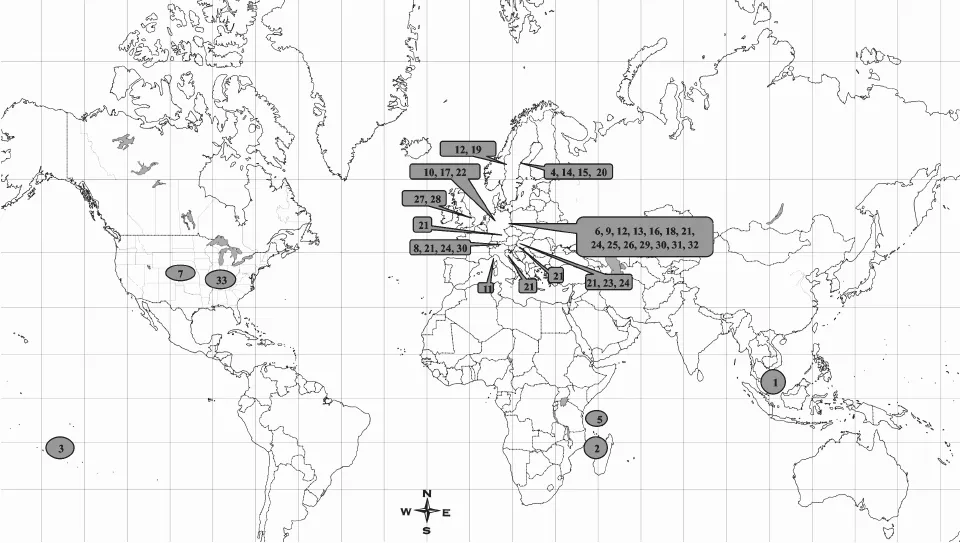

To facilitate an understanding of the complex interrelationships between tourism and climate change mitigation, the book’s main text is accompanied by 33 case studies from 17 countries of companies and organizations under the heading ‘Carbon Management in Focus’. These provide in-depth descriptions of innovative management strategies, where possible in combination with calculations of carbon savings, costs and profits – the latter either financial or including marketing, branding, loyalty, insurance or other benefits. This division was chosen for various reasons. First of all, not all readers will be interested in a full review of the carbon management field in the context of tourism. For these readers – and everyone else – Carbon Management in Focus provides a shortcut to an understanding of how leading innovators have managed to achieve carbon reductions, often providing details that could not have been integrated in the main text without interrupting the flow. Carbon Management in Focus also provides practical advice: in tourism, role models are of great importance, as the sector is not usually innovative and relies on ‘tested’ ideas (see Hall and Williams 2009). Vice versa, for readers of the main text, which is more theoretical in character, Carbon Management in Focus provides readable illustrations, practical examples and advice, often with comments from the respective companies’ and organizations’ sustainability managers (who might now be termed ‘carbon managers’).

With regard to the case studies, examples were identified through journal articles presenting specific businesses, personal contacts, colleagues’ recommendations, a request made through the Tourism Research Information Network, and Internet searches. In total, some 50 suitable case studies were identified to cover a variety of carbon management strategies. This number declined to 33, however, as some companies were not willing to reveal details of their management strategies, while others had to be dismissed as not being credible. As indicated in Figure 1.2 there is a heavy focus on Europe, where most of the case studies are located. This should not come as a surprise, however, as Europe has a comparatively long history of modern environmental awareness, environmental policy and legislation, as well as an interest by companies to act pro-environmentally that has evolved subsequently over the past three to four decades. Europe is also the first region in the world that has seriously considered climate change mitigation in its policy, and implemented an Emission Trading Scheme (ETS), which ran through its first trading period in 2005–07, and has now entered its second trading period (2008–12). Awareness of emissions and the

need to reduce these is consequently high. However, many other case studies have been identified elsewhere in the world, covering all continents and even remote countries such as French Polynesia.

With regard to the strategies chosen to reduce emissions, case studies explore options to eliminate, substitute, reduce and offset emissions, the latter referring to compensational measures for emissions that cannot be avoided (see UNEP-Oxford University-UNWTO-WMO 2008). As elimination, substitution, reduction and offsetting are embedded in the overarching framework of technology, management, education, behaviour, politics and research, these are chosen as the thematic arenas within which mitigation approaches are discussed. Note that case studies represent all transport sub-sectors with the exception of aviation, as no larger airline with a credible strategy to achieve absolute emission reductions could be identified. Case studies also include accommodation establishments, restaurants, attractions, destinations, travel agents and tour operators. Approaches to carbon management do not only include the measures carried out to reduce emissions, but also describe the processes necessary to involve actors and to communicate climate change mitigation goals. Each of the case studies highlights a specific aspect of carbon management that is innovative and original, even though few of the case studies can be seen as fully comprehensive approaches to climate change mitigation.

To illustrate this with an example: Costa Rican NatureAir, though not a case study in this book, is an airline that has chosen to compensate for all of its emissions, clearly an innovative practice, given that few airlines acknowledge their contribution to climate change in the first place. In order to compensate its contribution to global warming, NatureAir pays for rainforest conservation projects, based on the notion that the preservation of tropical forests is only possible when compensation for sustainable use or strict protection is paid. This is a logic many would follow. However, even if it can be shown that a rainforest tract is threatened by conversion and that payments will prevent this – implying proof that deforestation or forest degradation does not simply shift elsewhere – conservation will mean that a carbon pool is maintained, but it does not mean that an additional sink corresponding to emissions from the airline is created. In other words, if compensation works on the basis of forest preservation, atmospheric CO2 concentrations would still increase. Consequently, as an offset, forest conservation is an ambivalent option, even though it is undoubtedly essential to preserve global forests. For many of the case studies presented in this book, similar concerns could be raised. All have in common, however, that carbon management is economically viable and desirable, with only a few case studies having implemented measures that do not pay off in shorter timeframes.

All case studies are presented in an identical way: the company name and specific field of carbon management are presented in the title. In a short introduction (‘The issue’), the need to engage in climate change mitigation is motivated. This is followed by ‘The solution’, a section briefly introducing a company or organization and its carbon management strategy, including a detailed description of the carbon management approach, difficulties encountered in implementation, costs involved, and goals achieved – where possible measured in terms of economic savings (€) or GHG reductions (t CO2), recognition through awards, positive customer perspectives, brand-building, or growth in customer numbers. The importance of the approach chosen for the development of low-carbon tourism systems is discussed in a concluding section (‘Impact’). Finally, related websites, useful links and references are provided at the end of the case studies.

Case study material was often collected with considerable effort, including the screening of relevant websites, search for academic papers or reports, and personal contact with the companies and organizations to gain knowledge about implementation processes or access to more sensitive data not posted on websites. The geographical distribution of the case studies warrants more research into areas such as South America, Africa and Asia, where more relevant approaches to carbon management might be found.

2

Climate change mitigation

Reasons for advocacy

There are many reasons for tourism stakeholders to embrace climate change and carbon management as a key challenge. A selection of arguments are discussed in the following in more detail to create a normative basis for this book, including (1) moral dimensions of climate change mitigation, (2) the vulnerability of the global tourism industry to climate change, (3) rising energy costs as an increasingly important factor in operational costs, (4) the low efficiency of current tourism operations, where much energy is wasted, (5) emerging climate policy seeking to make GHG emissions more expensive, (6) growing public awareness of climate change and expectations for businesses to engage in mitigation, and (7) the importance of an understanding of climate change and its consequences for longer-term strategic planning.

MORAL DIMENSIONS

The environmental and economic risks of the magnitude of climate change projected for the twenty-first century are considerable and have featured prominently in recent international policy debates (see Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) 2009; G8 2009; Stern 2006). The Stern Review (Stern 2006; see also Stern 2009), a key document focusing on the economics of climate change, has stated that the costs of taking action to reduce GHG emissions now are much smaller than the costs of economic and social disruption from unmitigated climate change in the future. Notably, the costs of unmitigated climate change are not evenly distributed, and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has concluded with very high confidence (IPCC 2007a) that climate change would impede the ability of many developing nations to make progress on sustainable development by mid-century (see also United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) 2007; Asian Development Bank 2009). In many countries, climate change is projected to lead to increasing conflicts and severe human suffering. Burke et al. (2009), for instance, show that warmer years in sub-Saharan Africa have led to significant increases in the likelihood of war because of reduced access to food, and project a greater than 50 per cent increase in armed conflicts in sub-Saharan Africa by 2030.

The Global Humanitarian Forum (GHF) (2009: 1) indicates that climate change already seriously affects the livelihoods of 325 million people, causing 300,000 deaths per year and economic losses of US$125 billion (see also McMichael et al. 2003; Patz et al. 2005). Four billion people are regarded as vulnerable to climate change, and 500 million people are at extreme risk with an estimated half a million lives expected to be lost because of climate change by 2029. Burke et al. (2009) suggest that an additional 390,000 people could die in sub-Saharan Africa because of an increase in warming-related armed conflicts by 2030. In terms of non-human losses, a considerable share of species could become extinct because of climate change (e.g. Pounds and Puschendorf 2004; Thomas et al. 2005)....