![]()

1 Water is the new carbon

However it is viewed, the movement of water forms a considerable component in the taming of the environment in our modern world. From the channelling of flows for water supply to the transport of waste, sewerage and rainwater away from habitable space, this important aspect of engineering is both taken for granted and ubiquitous in equal measure. The challenge has always been to understand a system that most users are unaware of. It could be argued that the current challenge of ‘climate change’ occurs on a continuum, from a developed world perspective, encapsulating issues such as social reform and the linkage of sanitation systems to public health issues in the nineteenth century, large infrastructure projects post both world wars in the twentieth century, environmental concerns in the 1970s and 1980s and continuing water conservation and resource management concerns up to the present. From the global perspective it can be noted that the rapid urbanisation in the last half of the twentieth century leaves more than half the world’s population without clean water supply and adequate sanitation provision (Gormley et al. 2013), arguably, at a different point in the continuum. While the nature of the challenge changes, the fundamental engineering questions remain very similar.

From a practical perspective, the recent focus on a changing climate in relation to water and wastewater removal from buildings centres on the ability of systems to continue to operate efficiently with the changing demands placed on their functionality from the extremes of too much water and too little water. What has become clear is that the issue of climate change has become more than a discussion of carbon emissions, but rather a wider discussion on mitigation and adaptation approaches which inevitably lead to the need for more holistic approaches. As a fundamental of human existence, water availability and management is seen as central to the debate, leading some to contend that ‘Water is the new Carbon’ (Swaffield 2008).

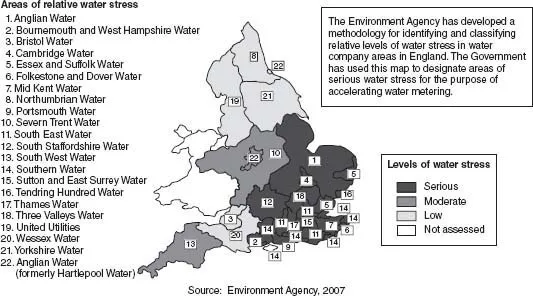

It has been established, and widely accepted, that climate change has led to a multiplicity of water-based problems, ranging from the accepted increase in sea levels to increased hurricane frequency and severity and precipitation increases due to rising sea water temperatures. Along with the probability of increased severity and frequency of rainfall, with consequent flooding, water shortages are also a challenge for systems engineers. Areas of water stress in the UK have been established (Figure 1.1), and similar issues are raised in other areas.

UK government predictions for climate change, June 2009, aimed at industries and organisations that need to make long-term investment decisions that could be influenced by climate change, suggest that summer rainfall in SE England could fall by 19% by 2050 and possibly (1 in 10 chance) by 41%. Winter rainfall in the West of Scotland will rise by 15% by 2050 and possibly (1 in 10 chance) by 29%. In launching these new scenarios Hilary Benn, the UK Environment Secretary said that ‘climate change is the biggest challenge facing the world today … this landmark scientific evidence shows that we need to tackle the causes of climate change and deal with its consequences’ (Guardian report of Benn’s presentation, 19 June 2009).

In the UK, the importance of building water supply and drainage has been promoted by government departments such as the Department of Communities and Local Government (DCLG) and the UK Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) in their development of new policies and advice to designers and users in the Part G Building Regulations, and a companion publication, in the CIBSE Guide series, CIBSE Guide G: Public Health Engineering (Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers 2009). Similar policies have been followed by governments around the world. Handling the consequences of climate change requires research-led initiatives that feed through to dissemination of subject knowledge and design guidance.

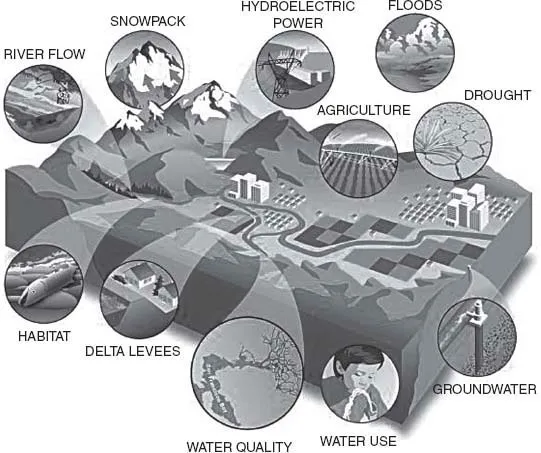

The water-based climate change issues shown in Figure 1.2 have all led to policy-related initiatives, and while this sets political agendas, the engineering fraternity have two major advantages in dealing with climate change – there is the intellectual ability to understand the science of our planet and the innovative ability to transform that scientific understanding into engineering solutions. Efforts to mitigate climate change will require more rather than less technology to stand beside the renewable ‘green’ agenda. Therefore it is expected that ‘big engineering’ in the form of tidal barrages, new hydroelectric proposals, an enhanced nuclear industry, the development and application of carbon sequestration and a possible national water grid will be solutions that should be welcomed, possibly providing both climate change modification as well as Rooseveltian economic solutions (Swaffield 2009b).

Figure 1.1 Levels of relative water stress in the UK.

Figure 1.2 Water-based climate change issues. (Source: Environment Agency).

1.1 Too much or too little?

The challenges associated with the provision and management of water in the built environment centres around two major contradicting phenomenon: too much and too little water. This is clearly an over simplification of many of the complex water supply and drainage management issues facing professionals in the industry; however it is a useful starting point in classifying the challenges.

1.1.1 Too little water

Globally, the distribution of water availability is uneven, dependant on local resources, both natural and financial, leading to a water stress. Water stress is defined by the intergovernmental panel on climate change (IPCC) as a situation in which the availability of water ‘directly affects human activity’ and has been quantified as an availability of 1000 m3/capita/year. In many parts of the world (in arid areas for example) there is a considerable requirement from systems which have become or which are becoming depleted. Work by Arnell (2004) highlights the expected changes in water stress around the world under a range of climate change scenarios. Using a number of respected climate change models (HadCM3, ECHAM4, CGCM4, CSIRO, CFDL and CCSR) the work concluded that by the 2080s, with the exception of South Asia and the Northwest Pacific and some parts of West Africa, more people will experience an increase in water stress than will experience a decrease. The case for North America, Europe and the Mashriq1 is expected to be particularly severe as is central and Southern America, although to a lesser extent.

It can be argued that the change in water supply per capita requirements creates a challenge in itself for engineers seeking security of supply and quality. A cursory look at the per capita water usage in different places highlights the nature of the problem.

Daily per capita use of water in residential areas:

• 350 litres in North America and Japan

• 200 litres in Europe

• 10–20 litres in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Efforts are inevitably focussed on reducing the daily per capita usage for North America, Japan and Europe while trying to increase the daily per capita in Sub-Saharan Africa. The imbalance in population, and population growth, coupled with insufficient infrastructure and water resources makes this a monumental task.

As the resource is becoming scarce, tensions among different users may intensify, both at the national and international level. Table 1.1 shows a classification of water stress levels on a global scale, and while developed countries are not suffering in the same way at present, higher levels of stress are expected as resources become more scarce. Over 260 river basins are shared by two or more countries. In the absence of strong institutions and agreements, changes within a basin can lead to trans-boundary tensions. When major projects proceed without regional collaboration, they can become a point of conflict, heightening regional instability. The Parana La Plata, the Aral Sea, the Jordan and the Danube may serve as examples. Due to the pressure on the Aral Sea, half of its superficy has disappeared, representing two-thirds of its volume. 36 000 km2 of marine grounds are now covered by salt.

Table 1.1 Water resources index classes

Resources per capita (m3/capita/year) |

Index | Class |

>1700 | No stress |

1000–1700 | Moderate stress |

500–1000 | High stress |

<500 | Extreme stress |

Source: Arnell 2004.

UN initiatives have consistently failed to achieve their objectives due to the scale of the problem, lack of resource and motivation and political instability in areas most in need of support. The 1980s UN ‘Decade of water’ singularly failed to meet its objectives, and the necessity to improve developing country water and sanitation provision, together with the challenges posed by global urbanisation, continues to be daunting. The current millennium development goals (MDGs) will have fallen short of the sanitation target by a long way, while access to water supply is improving (UN 2011).

In the UK, along with other developed countries, water shortage is exacerbated both by local shortfalls in precipitation and by our choices as to urban location and life style. Current Defra proposals indicate a reduction in water usage from 150 litres per capita per day to 120–130 by 2030. This aspiration has to be seen against a background of climate change that over the same period is expected to result, in the southern UK, in high summer temperatures and dry conditions, while extreme winter precipitation will become a normal event.

While efforts have inevitably focussed on water for drinking, since this is a fundamental requirement for a healthy human existence, there are water-related issues from a sanitation perspective.

The issue is often divided between engineering challenges in the ‘developed world’ and the ‘underdeveloped’ world making a distinction based on infrastructure and resources.

Table 1.2 highlights the global challenges for water supply and sanitation, regardless of economics. There are differing and often competing demands on systems; for example, systems must have enough water to be self-cleansing whilst not overusing valuable potable water. Alternatives are complex and often counter-intuitive. For example, in order to reduce the risk of blockages in a system with low water use, it is often prudent to decrease the pipe diameter, thus increasing the water depth, decreasing the wave attenuation and facilitating better solid transport.

A cursory glance at Figure 1.3 indicates the extent of the challenges. In 1900 the average flush volume was 40 litres; today, with even further drives hoped for the pressure is to reduce on 6 litres, with 4/2 litre flushes not uncommon. It is easy to imagine the different solid transport characteristics with such a difference in applied surge.

Table 1.2 Global water challenges

| | Developed world | Underdeveloped world | Developing world |

Water resource for drinking | Generally available – high cost and subject to localised stress Water usage per capita high Changing demographics | Availability variable Lack of infrastructure | Rapid growth in distribution and processing infrastructure difficult t... |