Part I

Preclassical Economics

Key dates

| c. 369-370 BC | Plato | The Republic |

| c. 355 BC | Xenophon | The Ways and Means to Increase the Revenues of Athens |

| c. 300 BC | Aristotle | Politics, The Nicomachean Ethics |

| c. AD 1269-1272 | Thomas Aquinas | Summa Theologica |

| c. 1360 | Nicholas Oresme | Tractatus de origine natura jure, et mutationibus monetarum |

| 1613 | Antonio Serra | Breve trattato delle cause che possono far abbondare li regni d’oro et d’argento, dove non sono miniere con applicazione al Regno di Napoli (A Brief Treatise on the Causes Which Can Make Gold and Silver Plentiful in Kingdoms Where There Are No Mines) |

| 1664 | Thomas Mun | England’s Treasure by Forraign Trade |

| 1690 | Josiah Child | Discourse about Trade |

| 1690 | Sir William Petty | Political Arithmetick |

| 1692 | Dudley North | Discourse upon Trade |

| 1696 | Nicholas Barbon | A Discourse concerning making the New Money Lighter |

| 1714 | Bernard de Mandeville | The Fable of the Bees: or Private Vices, Publick Benefits |

| 1752 | David Hume | Political Discourses |

| 1755 | Richard Cantillon | Essai sur la nature du commerce en général |

| 1767 | James Steuart | An Inquiry into the Principles of Political Oeconomy |

Why study the history of economic analysis in the twenty-first century?

The first decade of the twenty-first century marks the beginning of a globalized economy. The free movement of information made possible by the internet, coupled with greater mobility across international boundaries aided by such trading agreements as the North Atlantic Treaty Agreement (NAFTA), the European Economic Union (the EU), and the Asian Agreement, which facilitate less restricted movements of commodities, services, and capital funds, presented practical men and women with a host of new problems. Despite the claims made for economics as a science of rigor and relevance, there are numerous problems about which economists are unable to agree, either about theoretical explanations or policy agendas. High on the list are how employment can be provided for all who are willing to work at the currently prevailing level of wages and prices. Whether and how can inflation be contained without creating unemployment? Perhaps the most difficult question of all is “Can income be distributed to support a ‘middle class’ in post industrial economies, while also improving the status of impoverished workers in developing countries?”

These problems are complicated by the fact that the economics of the “newly emerging” industrial economies of Asia and eastern Europe have long histories of state management, to which the principles of capitalist economies do not apply. Replacement of the administered prices of a planned economy with market-determined prices requires complex legal, institutional, political, and cultural changes, which will no doubt require several generations to become realized, even though the process of globalization promises that the combination of personal computers and the internet will promote a rapid transfer of technical knowledge and information about its use. Nevertheless, problems to be confronted suggest that not only economists, but thinking non-economists will gain a significantly better understanding of the changing material world inherent in a globalized economy if they are familiar, not only with modern-day neoclassical (or mainstream) principles, but also the way in which it developed.

Many modern-day economists, especially in English-speaking countries, believe that contemporary theory embodies all the valid intellectual breakthroughs and insights of earlier contributors to the discipline. If this is a valid viewpoint, it follows that younger scholars ought to be taught these cumulative “foundations” as a basis for progressing toward the frontier of new economic knowledge. According to this view, time spent studying the history of economics, while interesting in its own right, does not advance the knowledge frontier.

However, the latter is a view not shared by all economists, if for no other reason than that it suppresses present-day challenges to the dominant neoclassical view. Also, it is these heresies, criticisms of which provoked acknowledgement that earlier theories embodied errors or inconsistencies, that led to the refinements that characterize what might be termed the “canon”; that is, the belief system reflected by the neoclassical economics of the mainstream.

The neoclassicism that rules today reflects the intellectual marriage of the classical tradition that preceded it, enriched by the traditions of general equilibrium analysis, marginalism, and the challenges they confronted over time from thinkers like J. M. Keynes, Karl Marx, the Austrians, and members of the historical school and their contemporary followers who dissented from their views, and carry on the pluralism of modern heterodoxy. The latter reflect other economic belief systems that differ from the scarcity-equilibrium questions of neoclassical economics, and offer alternative explanatory hypotheses about economic phenomena.

The difference between heterodox perspectives and neoclassical economics may be likened to the classic example of the sciences of astronomy. From the time of the ancient Greeks until the fifteenth century, Ptolemaic theory (after the Greek astronomer Ptolemy) maintained that the Earth is the center of the universe. The counter-argument by the Polish astronomer Nicolas Copernicus (1473–1543) was that Earth is but one planet among many that revolve around the sun, which destroyed forever the old Egyptian belief.

There has never been the equivalent (nor is it likely that there ever will be) for the Copernican revolution in economics. Unlike the natural sciences in which new evidence totally supplants old theories, alternative paradigms in economics have not only survived from the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, but have become refined and modernized doctrines known as Institutionalism, post-Keynesianism, Modern Austrian, and Marxism (or Radicalism), which are the most prominent contemporary challenges to the neoclassical or mainstream paradigm.

One can, of course, study contemporary economic issues and problems without any paradigmatic perspective other than the conventional wisdom of the neoclassical theory that emerged when the classical tradition of Adam Smith and David Ricardo was joined to nineteenth century Marginalism by Alfred Marshall (1890). The latter was subsequently joined by J. R. Hicks to integrate John Maynard Keynes’s macroeconomic principles into Marshallian price theory. Subsequent to its mathematical restatement by Paul Samuelson, this synthesis came to constitute the “core” of contemporary economics. Even if one is persuaded that neoclassical principles do offer the most robust and sophisticated hypotheses articulated until now to explain how modern econ-omies function and progress, it should be recognized that neoclassical principles are themselves the product of considerable intellectual change and challenge. The neoclassical—neo-Walrasian tradition that rules today reflects the intellectual marriage of the classical tradition that preceded it and the traditions of Walrasian general equilibrium analysis, marginalism and the challenges they confronted from Marxism, Historicism, Institutionalism, and the economics of J. M. Keynes. Familiarity with only contemporary economic theory, without any historical understanding of how it came to be, is thus likely to be relatively unsophisticated. The principles of modern economics rest, in large part, on historical conceptions about what the issues of economics are and what are the methods by which answers shall be sought. Economics has become a science of multiple paradigms whose competing claims to validity comprise the basis for contemporary controversy. Thus, the concluding Part VII of this book concerns contemporary heterodox economics, which examines the leading competing paradigms that have emerged to challenge neoclassical theory.

While the history of economics is worth studying for its own sake, a more positive reason for studying it as the problems of the twenty-first century emerge is surely to understand what are the questions that economists ought to ask, and by what methods shall they seek to answer them? It is not an exaggeration to say that economics did not exist as a separate field of study prior to the eighteenth century. Even in advanced ancient civilizations, such as those achieved by the Greeks and Romans, inquiry into economic matters was quite a minor aspect of intellectual effort. Yet the inquiries of many pre-eighteenth-century writers are so profound, and continue to have so great an impact on the way in which human beings conceive of their relationship to one another and their environment, that they are remembered as part of the intellectual heritage of western civilization.

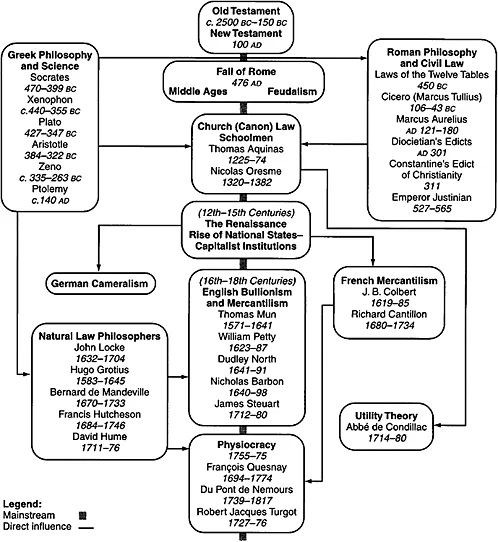

An overview of pre-classical economics

The writings of Aristotle, Plato, Aurelieus, Oresme, and Aquinas are among the masterworks of human knowledge bequeathed by the ancients. While the inquiries of the ancients into economic questions are unsystematic, and in most cases little more than moral pronouncements, it is also the case that even those thinkers who, like Aristotle, had a desire for knowledge for its own sake were most concerned about the solution of practical problems. The philosophical studies of the ancient Greeks and Romans were undertaken in the context of particular issues and problems. It was they who taught us to seek solutions for practical problems, including those that arise in our complex present-day material environment. The modern word “economics” has its origin in the Greek word oikonomia, which means the art of household management. In studying the nature of this art, Aristotle undertook to examine what is probably the first economic issue to have been subjected to formal inquiry: what sort of wealth-getting activity is necessary and honorable for humans to undertake? While Aristotle’s was an ethical and moral question, it was answered by means of reasoned inquiry. That one of the areas about which knowledge should be sought concerns human relationships as they relate to the material environment, was a major intellectual departure for which we are indebted to early Greek thinkers like Aristotle.

Roman and medieval thinkers also adopted a problem-solving perspective, particularly about practical applications in jurisprudence and animal husbandry. Their concern was with solving specific problems and answering specific questions, many of which related to the material environment. Their intellectual legacy is pre-scientific and pre-classical in the sense that it does not represent a body of general principles about economic matters, but observations and prescriptions relating to the good life or good citizenship embedded in writings concerned chiefly with religion, ethics, politics, or law. Even inquiries made during the vital era known as the Renaissance failed to produce anything in the way of systematic principles or analysis, and so these were substantially delayed until seventeenth-century mercantilist thought.

The development of quantifying concepts and techniques has accompanied the growth of knowledge throughout human history. In earliest times, their principal use was rooted in such practical undertakings as the building of roads, dams, and canals, in particular by the Romans, and magnificent burial sites, such as the pyramids of Egypt. The ancient Greeks, as philosophers and geometers, were generally less interested in the practical application of numeracy. Socrates, on the other hand (according to Plato), even though he was not interested in quantification per se, seems to have anticipated the expectations of many contemporary economists about the potential power of quantification as a learning tool when he said “the arts of measuring and numbering and weighing come to the rescue of human understanding, and the apparent greater or less, or more or heavier, no longer have mastery over us, but give way before calculation and measure and weight.”1 Given the present-day reliance by economists on mathematics and on econometrics as the sister discipline of economics, the study of the development of economic analysis is quite appropriately extended to include reliance on what may broadly be called “numeracy,” as it came to be used during different historical stages of inquiry into economic phenomena.2

A quantified or numerical variable is one whose values are expressed as numbers which measure a particular property or characteristic using a specific ordinal, cardinal, or ratio scale. By contrast, a non-quantified or qualitative variable is one whose values do not lend themselves to numerical expression. We will use the term “numeracy” as a convenient “catch-all” for all the techniques that have been used by political economists, and subsequently by economists, to enumerate, measure, and quantify, ranging from simple arithmetic to contemporary econometric techniques.3 The revival of trade from the fifteenth century onwards gave an impetus to financial techniques such as double-entry bookkeeping and bills of exchange. These coincided with the era of mercantilism, which was characterized by strong national economies that pursued commercial activity as an instrument of statecraft. Mercantilism’s chief goal was to increase the political power and wealth of nation-states with respect to one another.

Mercantilistic goals directed economic activity and thought in England, France, and northern Europe from the sixteenth century well into the eighteenth century. Some theoretical ideas, and also what may be termed “the first stage” of numeracy, date from this time. The transition period of the mid-seventeenth to the mid-eighteenth centuries was thus a time that was animated by many inquiring minds, and was a period of great economic vitality during which a substantial middle class engaged in industry and trade came into power, particularly in England, but also in France and Holland. These economic developments were accompanied by an attitude of increasing liberality: people began to believe that greater freedom from governmental restrictions would be advantageous to themselves as well as to the economy. Economics had not yet become established as a separate discipline, perhaps because there was so much theological and political controversy and such great interest in the natural sciences. However the ground from which the classical tradition subsequently germinated was being prepared.

The three chapters that follow examine the highlights of pre-classical economics and their legacy as masterworks in economics.

Notes

1 Keynes, J. M., The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (New York: Harcourt Brace and Company, 1936), p. 383. Donald A. Walker offers a contemporary retrospective rel...