Stories about beating and being beaten are common in the folk psychology of everyday life. One such story operates as a parable: A worker is humiliated by his boss. This worker then goes home and beats his wife, who then hits her child, who then kicks the dog. It is a simple story but one that carries a potent psychological idea about the dangers of displaced aggression and how feelings of powerlessness and rage are readily displaced from an original source of anger onto a less threatening person or object. The story also illustrates how family hierarchies operate as shock absorbers in the world of work, since the story begins with deference to an abusive boss.

While this story contains a kernel of folk wisdom, the plotline may obscure important differences in forms of power that operate at various sites where aggression is displaced from one object to another. For the man who submits to the power of a boss, home is indeed a place where he can retreat and recoup his injured pride. Further, the release of aggression does not offer the same return for the wife, the child, or the dog as it does for the man. Whatever cathartic value in the displaced aggression of the wife or the child, there is less cultural entitlement for them to make someone pay for their misery. Feminists in the battered women’s movement struggle to restructure such tales about family violence and to show how gender operates as a site of unequal emotional and economic exchange (Dobash & Dobash, 1979; Martin, 1976; Schechter, 1982; Yllo, 1993). In some feminist re-tellings of the parable, the wife/child/dog trio occupies the position of the subjugated, with the husband as lord and master. From this perspective, there is only one story to tell: The man beats his wife.

While this feminist re-telling interrupts the chain of perpetually displaced responsibility for aggression, it represses the many variations in women’s stories about family violence, as well as the problem of displaced aggression in oppressed communities. In Pedagogy of the oppressed, Paulo Freire (1970, 1999) describes this defense as part of the destructive legacy of colonization. Friere explains how developing critical consciousness requires some understanding of how the oppressed may turn a hated part of themselves, the bitter psychic toll of colonization, onto others among the oppressed.

This chapter draws out the dilemmas feminists confront in theorizing commonalities and differences in women’s experiences with violence by tracking those dilemmas through the history of the movement. This historical context sets the stage for subsequent chapters and a more careful reading of conflicts that surfaced. By working at the borders of group defenses in various locales and recognizing how defenses have a range of effects, both protective and destructive, we may be better able to analyze the impasses that emerged. One key question guiding this inquiry into the history of the movement centered on the development of social identities for advocates in the various settings. How did women come to identify with the issue of woman battering? And how did historical contexts shape the stories that emerged around woman battering?

In mapping the terrain of feminist identities that emerged in the various locales, I began with the assumption that women confront many of the same dilemmas as do men in monitoring in-group/out-group boundaries. Vamik Volkan (2009) argues that emotional investments in “us and them” distinctions form the central axis of large group identifications. Drawing on the object relations tradition in psychoanalytic theory and his own research in conflict zones around the world, Volkan suggests that humans are predisposed to projection and externalization of threats through their long period of early dependency. In recognizing that the loved maternal object is the very same as the object of its terrifying rage, the infant manages anxiety through an early form of splitting—of separating representations of the “good mother” (gratifying images or sensations) and the “bad mother” (disturbing or anxiety-provoking images and sensations). By keeping images of the bad object separate from the good object, the infant is able to preserve a good self/good object representation that protects against overwhelming anxiety. In the course of human development, children increasingly are able to integrate the good and the bad in themselves and in their primary attachments. Volkan suggests that periods of social crisis, whether threats of war or social upheaval, revive these infantile anxieties and forms of splitting associated with their management.

By attending more closely to stories about the history of the movement, we may be better able to understand sources of group conflict that arose in fighting male violence. As a starting point for accounts that unfolded in the interviews, the following section opens with a story about the first global summit of the movement and the uprising of international organizing that followed—a powerful event often lost in the collective memory of the movement.

A TALE OF MANY CITIIES

In 1976, over 2,000 women from 33 countries attended the International Tribunal on Crimes Against Women in Brussels, ushering in a dramatic moment in the early history of the campaign against woman abuse. Breaking from the traditional role of weeping wives, women cried out in a chorus of outrage. In combating woman battering, the women called for the “complete restructuring of the traditional family.” Diane Russell describes the radical demands women voiced at this historical event:

Whether liberal, radical, or socialist in their politics, feminists shared a critique of the patriarchal family (Donovan, 1996). Founded on principles of human rights, specifically the right to be free of terror and torture, the animus of the anti-battering campaign was its foregrounding of the home as a dangerous zone for women (Dobash & Dobash, 1979; Martin, 1976). The contract under patriarchy in the capitalist era offered women protection and economic support in exchange for services provided in the context of marriage. The battered women’s movement exposed this contract as fraudulent, pointing out that women were at greater risk in their homes than on the streets (Koss et al., 1994; Walker, 1979b).

Achieving economic independence from men was a shared premise, but feminists diverged in their analyses of the obstacles women faced once they crossed the threshold of the household and entered the labor force. While some feminists viewed patriarchy as the basic problem and gender as the prototype of other systems of domination, other feminists argued that gender oppression varied historically and worldwide, and that social class was more fundamental than gender in structures of domination (see Donovan, 1996; Schechter, 1982). Still other feminists introduced dual systems models in situating the oppression of women. In one of the seminal texts on woman battering, Del Martin (1976), for example, combines a critique of capitalism and a feminist analysis of the patriarchal family, arguing that capitalism benefits from the free labor performed by women in the household, just as individual men benefit from the domestic services of women. Advancing this economic analysis, Martin (1976:41) explains that “If society succeeds in pressuring women to remain in the home, the labor market is cut in half, and competition for jobs, money, and power is therefore cut in half.” Upper-class women exert power over working-class men, many socialist feminists pointed out, as well as over working-class women, for example, as household servants (Schechter, 1982).

The large-scale entry of married women into the waged workforce in the wake of the women’s movement of the 1970s did open ground on the domestic front for resisting abuse. Even in low-wage or part-time jobs, women could achieve a degree of independence from men. Women were no longer expected to stoically endure bad treatment from men, in part because more economic options were now in sight. The ideal of the patriarchal nuclear family ideal, with a male breadwinner at the helm and a female nurturer at the hearth, had been destabilized as had the notion that traditional gender roles were natural (Brenner, 2000; Gordon, 2007).

The very prospect of greater options for women intensified, however, the stigma attached to battered women. As Lenore Walker (1979a) notes in her introduction to The battered woman, money is no guarantee of protection against male violence. Women stay in abusive relationships, not because they are masochistic but “because of complex psychological and sociological reasons” (1979a:ix). This early recognition of complexity soon encountered a wall of resistance, however, as feminists took on the state. Through a feminist lens, “psychological reasons” could be viewed as code for locating grievances of women in an over-reactive female psyche. The social symbolic power of the battered woman for many feminists was in her capacity to display hard evidence of the brutality of patriarchy.

In breaking down the barrier separating private and public life, a barrier that allowed men to abuse their wives behind closed doors, women’s groups argued that the unwillingness of the state to enforce laws against assault and battery was a form of sexual discrimination (Goldfarb, 2000; Schneider, 1994). Further, this discrimination had a direct economic impact on women. Since much of the labor women performed was carried out in the household, and this labor contributed indirectly to the market, the federal government had an obligation to intervene on the basis of protecting women from domestic abuse (Schechter, 1982). With the criminalizing of wife beating and the reframing of the problem as one of woman battering, the gendered character of the crime was introduced. And in forging a linguistic and legal connection to battery, a felony, feminists were able to argue that it was a serious social problem that required intervention on the part of the state (Schneider, 1994). Abused women would no longer be left to fend for themselves in managing the violent men in their lives.

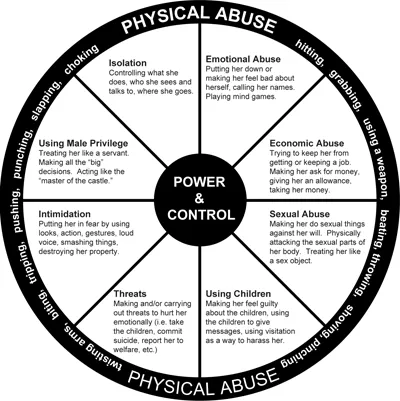

Yet the question of how the state should intervene on behalf of women, and the role of feminist organizations in negotiating with the state, emerged as a new site of conflict. In taking up this conflict, a program in Duluth, Minnesota developed a model that became the international standard in the 1990s for domestic violence intervention. Indeed, there are few products of feminist inquiry that have circulated as widely throughout the world as the “Power and Control Wheel,” published in 1993 as part of the Duluth curriculum for batterers. Developed by Ellen Pence and Michael Paymar (1993), the Power and Control Wheel was on display in most programs visited by members of my research team.

Later chapters discuss in more detail the Duluth model and the storytelling generated through this framing of the problem. Key premises behind the model are important to review at this juncture, though, in explaining how the Duluth model facilitated the transition of domestic violence from a radical feminist to a mainstream political issue. In interviews with advocates in the various settings, a key question concerned how the Duluth model functioned as a narrative framework and defensive boundary for feminist intervention.

A cornerstone of the Duluth model is its resolute rejection of therapeutic approaches to couple violence (Pence, 1989; Pence & Paymar, 1993). In ingroup/out-group terms, psychotherapy was cast as the enemy—the bad Other of a movement that had by the late 1980s expanded its borders considerably on the international front. Clinical work with batterers— whether in the context of individual, family, or group treatment—became associated with coddling abusers (Goldner, 1985; Gondolf, 1993; Kivel, 1996; Pence & Paymar, 1993). Therapeutic approaches distract attention from the political aspects of the problem, advocates insisted, by focusing on psychological dynamics or deficits.

As an alternative, the Duluth model frames battering as a direct consequence of patriarchy. In patriarchal societies, men develop a sense of entitlement to control and dominate their female partners. From this perspective, assaults on women are not seen as episodic but rather expressions of a systematic exercising of power over another person, which are highly reinforcing for the abuser. In addition to physical violence, tactics for subjugating women include emotional, economic, sexual, and verbal forms of abuse. Framed in this way, battering is intentional and a result of individual choice. Rather than a loss of control, violence is an assertion of control. The stated goal of the Duluth model is to hold men completely accountable for their violence. In the introduction to Education groups for men who batter, Pence and Paymar (1993) describe the acute need for educational programs for batterers after changes in the law led to a wave of mandatory arrests. “The courts refused to impose jail sentences on first

offenders without first giving them an opportunity to rehabilitate themselves” (1993:xiii).

In addition to groups for batterers, the Duluth model is associated with the movement toward “coordinated community response” (CCR) to partner violence. Part of CCR involves disallowing the testimony of the victim in adjudicating cases of domestic violence. The most consistent effect of this change in procedures was that the abuser’s fate was no longer in the woman’s hands: “The prosecutor would (now) not interpret a woman’s request to drop charges as a sign that she was safe but as a sign of her vulnerability” (Pence & Paymar, 1993:17–18). Controlling the behavior of batterers was now a community responsibility rather than that of abused women as individuals. Advocates of the CCR approach pointed out that the man’s behavior represents a threat to other women as well as to his present partner. In moving toward mandatory arrest and rehabilitation programs, the authors call for “increasingly harsh penalties and sanctions on men who continue to abuse their partners” (1993:18).

Court-mandated groups for batterers worked a compromise between these calls for harsher penalties, on the one hand, and concern over the broad sweep of the mandate, on the other (Feder & Dugan, 2002; Feder & Wilson, 2005). A key premise of the Duluth model, however, is that batterer intervention groups must be integrated into a broader criminal justice response. As an alternative to jail time, men are required to attend a series of groups where their progress is monitored by the courts. Some cases are adjudicated through criminal courts while others are adjudicated through family courts, depending on a range of factors, including whether children are invol...