Chapter 1

Seeing ourselves

What vision can teach us about metacognition

Rebecca Saxe and Shani Offen

When [split-brain patient] P.S. was asked, “Why are you doing that?”, the verbal system of the left hemisphere was faced with the cognitive problem of explaining a discrete overt movement carried out for reasons truly unknown to it. In trial after trial, when queried, the left hemisphere proved extremely adept at immediately attributing cause to the action. When “laugh,” for example, was flashed to the right hemisphere, the subject commenced laughing, and when asked why, [P.S.] said, “Oh, you guys are too much.”

(Gazzaniga et al., 1977)

How do we know our own minds? Does knowing our minds allow us to use them better? Or to live better? These questions are old, and urgent, and at the heart of interest in metacognition. Unfortunately, the scientific answers remain fractionated and confusing.

Intuitively, knowledge of one’s own mind seems simple and direct, quite unlike the effortful and error-prone inferences we make about other people, and more like visual perception of the world around us. To know one’s own thoughts and desires, it seems, we need only ‘look inward’, introspect, and our true states will be clearly visible.

In the current chapter, we explore the analogy between metacognition and vision, and its perhaps unintuitive implications. The analogy serves to organize existing data concerning metacognition from many disciplines, and to suggest new hypotheses for future investigations. Visual perception, we show, is not as dissimilar from knowledge of other minds as it first seems. We will describe how the resulting account of metacognition unifies evidence from developmental psychology, social psychology, neuroimaging and from studies of patients with brain damage.

Two meanings of ‘metacognition’

Metacognition has been studied in cognitive psychology in two largely unrelated literatures. The first literature concerns the ability to attribute beliefs and desires to oneself, to explain and justify actions and experiences. For example, I might explain that I ran home because I thought I left the keys in the door, or that I changed jobs because I wanted a shorter commute. We will call this aspect of self-knowledge ‘attributive metacognition’. The second literature concerns the ability to monitor and control ongoing mental activities. For example, I could decide to rehearse a phone number in order to remember it better, or to switch to thinking about a different section of this chapter in order to get past a mental block. We will call this second aspect of self-knowledge ‘strategic metacognition’.

Attributive and strategic metacognition differ from one another in both the objects of thought (beliefs and desires, versus mental activities and plans), and the actions taken (attribution in the service of explanation, versus monitoring in the service of control). In addition, they depend on largely independent neural substrates (as described below). In the psychological literature, strategic metacognition is closely related to work on executive function, the ability to switch flexibly between tasks and subgoals, and to inhibit unwanted options; attributive metacognition is closely related to work on ‘theory of mind’ (TOM), the ability to attribute psychological states to ourselves and to other people.

The current chapter concerns attributive metacognition, and the analogy with vision. At the end of the chapter, however, we will briefly return to the relation between the two aspects of metacognition: seeing one’s own mind, and knowing how to change it.

Visual illusions

Visual perception feels simple; we just see the objects and scenes in the world around us, when light bounces off their surfaces and reaches our eyes. It seems to us that we couldn’t possibly see anything else, given what’s out there in the world. Moreover, visual perception feels complete and highly detailed; at every moment we feel as if we are seeing everything before us. Decades of experiments and computational models in vision science belie this experience.

Vision poses an inverse problem: there are infinitely many possible arrangements of surfaces and light sources consistent with any given pattern of light on the retina. The input to vision is ambiguous and sparse, containing many gaps; yet these inputs are somehow transformed into a perception of a stable and highly detailed reality. The way in which the solution is achieved reflects the visual system’s goal: to quickly produce a single coherent interpretation, on which decisions and actions can be based. To make this possible, the inputs are disambiguated and completed by processes that take advantage of the system’s cumulative knowledge, encoded as prior expectations. Some of these expectations may be learned during our lifetime, and others built into the structure of our brains through evolution. In general the algorithms are effective, efficiently representing external reality, and providing a basis for action. However, systematic illusions reveal that this representation of external reality is really an inference to the best explanation, and can occasionally be ‘wrong’.

We suggest that metacognition shares these features of visual perception. As a consequence, the (relatively well understood) mechanisms of visual perception can provide a model for the mechanisms of metacognition. In particular, three features of the visual system provide instructive clues about the metacognitive system:

1 Perception depends both on current data and on prior expectations.

2 The subjective experience of a highly detailed, obligatory perception of the external world is an illusion.

3 Rapid construction of a single coherent interpretation is a central function of the visual system.

These features imply an intriguing fourth feature that may also be shared:

4 There is no dedicated mechanism for interpretation, separate from ‘visual processing’; rather, interpretation is suffused into every component of the visual system.

We will illustrate each of these four points in the visual domain, and then consider their extension to metacognition.

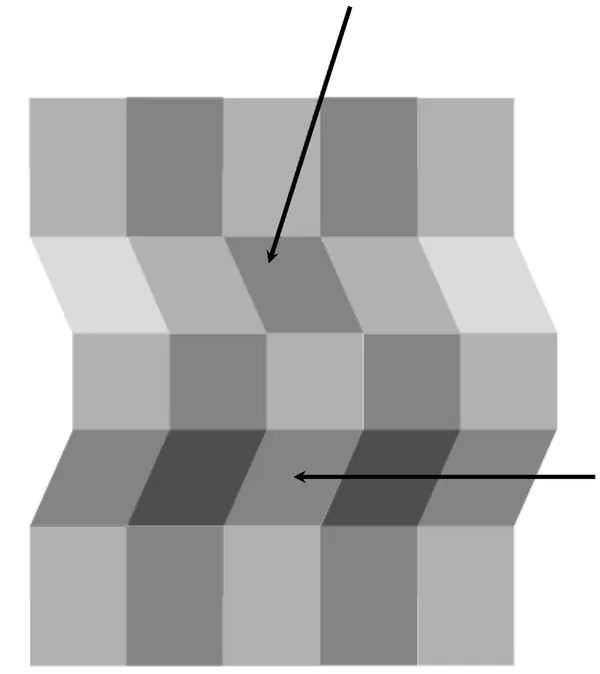

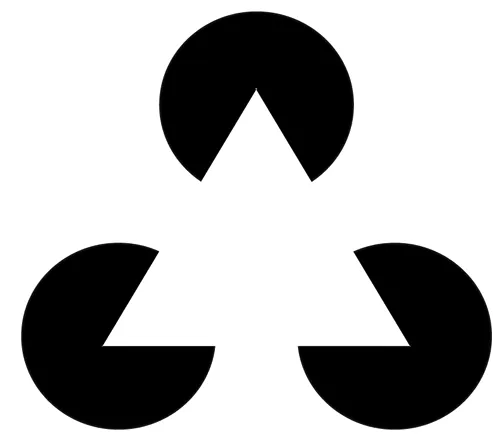

Prior expectations let us both disambiguate and go beyond the current data. For example, the visual system enforces a single coherent geometry, populated with smooth surfaces and few edges. It also discounts illumination sources when computing brightness, to achieve brightness constancy. These constraints are revealed by the Adelson plaid illusion (Adelson, 1993), in which the global geometric interpretation leads to big differences in the perceived ‘brightness’ of two patches of the image with equal luminance (see Figure 1.1). The visual system also enforces what it knows about statistical probabilities. If three dark pac-man shapes are suitably aligned on a light background, the visual system rules out coincidence. Instead, subjects perceive an illusory white triangle occluding the three black disks (Figure 1.2). This perception is rich: there is perceived depth (the white triangle looks as if it is above the black disks), as well as shading and contours (the triangle appears brighter than the background, and its boundaries are clear). In each of these illusions, at least one alternative interpretation of the scene, completely unlike the perceived interpretation, is equally consistent with the incoming data—namely, the true interpretation. Nevertheless, our visual system generates one stable percept, not a bistable percept or a mixture of both interpretations, and the percept is not uncertain or ambiguous. The

mechanisms involved ‘cover their own tracks’, and the intermediate, inferential stages of processing are inaccessible to introspection.

Also inaccessible to introspection is the extent to which even in the most unambiguous images we may retain only a small amount of the information afforded by the scene, and fill in the rest with untested expectations of what should be there. In change-blindness experiments (Rensink et al., 1997), for example, a visual scene is flashed on and off repeatedly. Successive frames are similar but not identical; the differences between the two frames can be large, central, and quite obvious when the two frames are shown simultaneously. When they are flashed in succession (even very slowly), though, it is often extremely difficult to detect the change. This demonstration

suggests that our introspective experience of continuously seeing a whole scene is itself an illusion. We experience a rich and detailed perception of the visual world; we don’t experience the gaps and ambiguities that our visual system is designed to cover. Change blindness doesn’t feel like anything. The world we perceive is just a fraction of what’s out there, but we are designed not to notice.

Visual illusions are not simply mistakes. Prior expectations are necessary for the visual system to fulfil its function: rapidly producing stable percepts that generalize across contexts, upon which decisions and actions can be based. Moreover, in most situations, the incoming data are consistent with prior expectations, so the single interpretation chosen by the visual system is usually ‘accurate’. To expose the hidden mechanisms, experimental situations have to be carefully constructed.

The nature of these hidden mechanisms may be particularly revealing for the analogy with metacognition. Naively, one might conceive of ‘input processing’ and ‘interpretation’ as two separate components of the visual system, housed in distinct brain regions and arranged serially. By contrast, experimental evidence from both humans and animals suggests that interpretation of the visual input is built into the architecture of the visual system at every level.

Illusions of metacognition

Like vision, metacognition feels simple; we just know our own thoughts and beliefs. Our introspection feels complete and highly detailed; we feel as if we have reliable access to our entire internal life. This surface of simplicity and directness is an illusion in metacognition, just as it is in vision. We suggest that metacognition shares the structural features we described in the visual system:

1 Metacognition depends on both current data and prior expectations.

2 The subjective experience of a highly detailed, obligatory perception of one’s own mind is an illusion.

3 Rapid construction of a single coherent interpretation is a central function of the metacognitive system.

These shared features suggest the possibility of a fourth:

4 There is no separate mechanism for self-interpretation; rather, interpretation is suffused into every component of the metacognitive system.

Attributive metacognition produces the best interpretation of our own behaviours in terms of mental states, based on the current data and prior expectations. Given data that strongly favour a single interpretation consistent with past experience, the system will settle on an accurate attribution. However, equally compelling interpretations will arise when the data are ambiguous, incomplete or inconsistent, or when strong prior expectations are violated by the context. These interpretations are metacognitive illusions; just as in the visual domain, such illusions provide a critical window on the hidden mechanisms.

Relevant input for metacognition may be missing for many reasons. For Gazzaniga et al.’s (1977) split-brain patient in our epigraph, the left hemisphere was missing information because it was surgically disconnected from the right hemisphere. When asked why she was laughing, the patient confabulated the most plausible explanation given the data her left hemisphere did have, along with prior expectations (people usually laugh for a reason, the experimenters are fairly odd people, etc.). As in visual illusion...