Chapter 1

Development of an ethical framework and the built environment

The built environment has been planned since the time of ancient civilisation and groups of humans started working together. History provides a rich source of anecdote and case study with plenty of opportunity to consider other cultural ways of delivery. Some ethical impacts can be assumed by comparing the parallel development of philosophical ethics and the success of the built environment.

The aim of this chapter is to consider the ethical principles which have evolved to the present day and their impact on delivering our built environment. The main points are:

- ethical principles in the development of the built environment;

- good and bad, right and wrong—various ethical approaches, virtue theory, natural law, justice and morality, proportionalism, utilitarianism, and relativism/situation ethics;

- applications to the built environment.

Development of building and its impact on ethics

Vetruvius (27 bc)1 wrote one of the earliest surviving texts on building. De Architectura consists of 10 books covering the subjects of architecture, engineering, town planning, landscape architecture, mechanical engineering, water supply, and material science, coming up with the fundamental building principles of durability, convenience, and beauty (often interpreted as firmness, commodity, and delight), and the design principles of order eurhythmy, symmetry, propriety and economy.2 He writes of the ethical responsibility of an architect:

As for philosophy, it makes an architect high-minded and not self-assuming, but rather renders him courteous, just, and honest without avariciousness. This is very important, for no work can be rightly done without honesty and incorruptibility. Let him not be grasping nor have his mind preoccupied with the idea of receiving perquisites, but let him with dignity keep up his position by cherishing a good reputation.

The idea of engineering was born and developed from the ancient Greek passion for science 300–400 years before Vetruvius. Civil engineering developed separately from military engineering, and applied science to roads, buildings and other permanent town structures, particularly under the Romans who were well known for their road and wall building. The Roman style was distinctive, and they built structures which accentuated civic pride and orderly government. The ethic of both these styles was to indicate the common good of society and the authority of government.

Vetruvius shows an amazing modern relevance in his perception of building purpose rather than self-promoting building. He referred to building economics as well as the values that different types of clients place on their buildings. He understood the nature of ‘place’ and the context in which the buildings stood, with special reference to public buildings. His chapter on defence may not be outdated in the security crisis that the developed world is facing today. He also understood well the principles of environmental science and the physics of building climate and hygiene.

The gothic style, mainly used in majestic religious structures, emerged in Europe from the eleventh to the sixteenth centuries and heralded the next great cycle of the master builder-designer. The gothic style emerged from the desire to let light into the great cathedrals and used the pointed arch, partly inspired by Islamic architecture, to enlarge the window openings and increase their slenderness. The ecclesiastical style of Islamic and gothic architecture were inspired by the ethic to glorify God and huge projects were devised and built over many decades.

Architects re-emerged under the Italian Medici-inspired drive for artistic differentiation in the sixteenth century with Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo. The symbolism and beauty of their work combined religious fervour and a more down-to-earth egoism, thus promoting elitism among leading Italian families, who were sometimes dubbed the Italian godfathers.

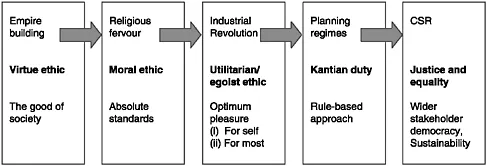

The Industrial Revolution started with the invention of steam engines at the end of the eighteenth century and rapidly changed the face of Western Europe and North America with the advent of power for manufacturing machinery for mass production and transport. This was the new golden age of steam with engineers such as Watt, Brunel, Whitney and Singer, who with restless energy lobbied the industry barons to invest in their schemes which championed the might and power of the entrepreneur. This was an ethic of industrial egoism to the glory of profit and achievement. Ecclesiastical and civic buildings were grand and represented an ethic of compensation and duty, with entrepreneurs using public buildings to provide beneficent charity. The development of mass production further organised and divided labour with entrepreneurs like Ford and F.W. Taylor who were the fathers of scientific management and reinforced the functionality and productivity motive at the end of the nineteenth century.

The Cadbury brothers and the Quaker movement in general provided a softer face to the welfare of the workers at the beginning of the twentieth century. In contrast to Ford and Taylor, they had a much more holistic approach in the ethic of Garden Cities where better living conditions within the metropolis were used to improve the work ethic and achieve a better work—life balance. During the nineteenth century, the design process split off from the construction process, and engineering and architectural practices began to build up professional societies which offered guarantees to the public of their competence and public responsibilities.

The age of the formal town planning regime slowly evolved from the beginning of the twentieth century to deal with slums and control large-scale rebuilding programmes. It produced opportunities for the private property developer after the Second World War when large tracts of urban land needed to be redeveloped. However, there was a tension between the egoism ethic of the developer and the Kantian (duty) ethic of the control regime represented by the planning authority. These acts were modified after the Second World War with the development of new towns and the setting aside of green-belt in the 1950s to reinforce a modern virtue ethic in the face of rising private development. Sustainability and public health are perhaps two ongoing issues that we need to face in the twenty-first century, which bring the need for more disciplinary integration into the building process, and they have re-ignited what might be called the corporate social responsibility (CSR) era, where large corporate organisations now require to pay much greater attention to the impact of building upon the environment and the social fabric of more sustainable built environments. All planning applications now also require a greater attention to sustainable features in buildings and property development.

Buildings have evolved through these series of ethical justifications (Figure 1.1), but later came the driving socialist contribution of providing jobs and places to live. This has taken different forms internationally. There is, however, a sense that this system has compromised the needs of development and the compromise arrived at may not satisfy all of the parties.

Kant’s deontological (duty-based) approach says the outcome is immaterial if the advice is entirely impartial and that we have fulfilled our moral duty to society. This satisfies certain moral behaviour towards each other, including honesty and fairness in an equal way—in short, our intentions need to be right. However, it is quite possible in the planning system for inequalities to appear and for one party to be favoured over another, depending upon their influence, their financial incentives or the lack of knowledge of others of the proposed impacts. Are planning systems tending towards a politically correct Kant-like duty-based approach emphasising the impact on others? If so, is this the ethical approach we want, or do we need to consider the quality of life factors of those who need to live and work in the buildings more than we currently do?

Figure 1.1 The development of ethical drivers of construction.

Integrated professional behaviour

Groak (1992: 61–62)3 reminds us how the building process brings together the treatment of design and building principles and further suggests that we distinguish falsely between white- and blue-collar workers (the thinkers and the doers) and that the building process is best delivered by recognising an integrated creative effort in design and production, which has not gone unnoticed in history. This is an ethical matter at the root of much division and has stilted development of the building process. Its resolution has the potential to lead us into more suitable forms of delivery for the twenty-first century. For example, boundaries now between the design, manufacturing supply and site production assembly processes are more blurred than previously, and new forms of procurement require us to break down the old divisions.

He also refers to the need for more building research to match the move from independent inventor to organisational research and development plans. Perhaps it is the slowness of the industry to move to a developing rather than a precedent-based governance of the building process that has earned it a reputation for being inefficient and giving less than optimal value to the client (Egan 1998;4 Latham Report 19945). It is the later Egan (2002)6 and Fairclough (2002)7 reports that have triggered a sustained drive in the UK to more efficiency and a more customer-orientated approach.

Ethically the two later reports put an obligation on the suppliers of design and production services in the built environment to integrate and get to know their customers’ needs and to work with them to increase transparency and commitment. Fairclough advocates more innovation in the industry to match needs rather than imposing old methods. It is a call for a combined outcome and process approach to delivering the project.

The basis of ethics—good and bad, right and wrong

Essentially ethics is actions that exceed a legal compliance. There is much debate in the philosophical arena about the definition of ethical behaviour. Many philosophers have sought to clarify the position of morality and ethics and have come up with many theories on the difference of emphasis between the concepts of good or right. Happiness or fulfilment have also been strong contenders in differentiating these theories and they can be easily split into consequentialist and non-consequentialist theories. Kantian, social contract and natural law theories are rule-based and concerned with good processes. They apply, whatever the consequences. Virtue ethics, egoism, utilitarianism and justice theories are concerned with good outcomes.

Virtue ethics

Virtue ethics is a moral approach with a concern for the community and the identification of desirable universal qualities. Virtues were formally espoused by Plato and were later developed by Aristotle who consolidated an ethical framework in his work Nicomachean Ethics, in 10 volumes. This is still a classic text for virtue ethics. In modern times, Alasdair McIntyre has developed virtue theory in a form called neo-Aristotleism and has helped to identify an application for virtue ethics in modern communities.

Plato, who lived in the fourth century bc, suggested that good was an absolute moral value and that morally no human being was capable of living up to the standard which was only possible for the gods. His theory of forms identified such things as beauty or justice or good and these forms were chosen as being timeless, spaceless, changeless and immutable. However, we live in a world dominated by time and space dimensions and compromise. His philosophy of ethical behaviour therefore referred to approaching the good and the perfect. He described activity and behaviour which was less than good as shadows which shielded the full view of the forms, but claimed that it was possible in a hierarchy of greater clarity to move into a purer light or, in his analogy, nearer the cave entrance.

In defining a good house, we might agree that there is a perfect match for the needs of the building users, but practically we might agree that some compromises might need to be made to mitigate harmful effects on others. In defining a good builder, we might think of quality or value for money or minimum risk or courteousness. Good in practice, then, is hard to define, but more of us might be able to apply the continuous improvement theme of getting closer to the ‘cave entrance’.

Plato lived in a stratified society called the State and distinguished three classes of citizen: the rulers, the soldiers and the people. He passionately believed in a behavioural ethic which was for the good of society. For each class he introduced the idea of a particular virtue or social quality which he believed should exist for...