- 150 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Dialects for the Stage

About this book

Dialect work is one of the actor's most challenging tasks. Need to know a Russian accent? Playing a German countess or a Midwestern farmhand? These and more accents – from Yiddish to French Canadian – are clearly explained in Evangeline Machlin's classic work.

Now available in a book-and-downloadable resources format, Evangeline Machlin's Dialects for the Stage is based on a method of dialect acquisition she developed during her years working with students at Boston University's Division of Theatre. During her long career, Evangeline Machlin trained such actors as Steve McQueen, Lee Grant, Suzanne Pleshette, Joanne Woodward, and Faye Dunaway.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

THE ACTOR, THE CDS AND THE MANUAL

Any actor who can sing a tune can learn to speak a dialect. Each dialect is like a song with words and music, the words having their own special pronunciationst, the inflections having their own special tune. The CDs give you the music and the words as spoken. The manual gives you the words written out. CDs and manual together enable you to learn any of the twenty dialects presented or either of the two standard speech forms of English that are included. Thus, you will see a dialect in print while you hear it in recorded sound. Following and learning with both ear and eye, you will begin to speak the dialect well in a surprisingly short time.

The CDs and the manual are arranged for the play-it-and-say-it method of dialect acquisition. This method was developed by me working with students of Boston University’s Division of Theatre over several years. A special method of spacing the first dialect selection in each groupon the CD permits you to reproduce it readily in short units. After this you proceedto longer ones, following a sequence explained in Part Three. Playing and saying the examples systematically and repeatedly, you soon become competent in reproducing them exactly, with their sound changes and inflections. Later you transfer these to other material in the dialect, then to improvised material, and so to the lines of a dialect role.

Dialect roles in plays are quite common. Entire plays in dialect are not rare. As an actor, the learning of accentsand dialects is a challenge that you must meet to improve your chances of being cast in a variety of roles. The first break into the professional theatre may be the hardest to get. An actor needs every possible asset, and skill with dialects can be an important one.

The term “dialect” in this manual refers to variant speech forms of English used by native speakers of English. The term “accent” is used for variant forms used by those whose native tongue is not English. However, one born in the American South, perhaps, or in the Lowlands of Scotland, who has spoken the speech of his region from childhood on, will be unlikely tocall his own speecha dialect. He is more likely to describe it as “my Southern accent” or “my Scottish burr,” perhaps because the word “dialect” seems to suggest uncultivated speech.

The CDs present three broad groups of examples: a North American dialect group, a British dialect group and a group of European accents. Two black African examples are presented in conjunction with black American. An accent that I have called “General European,” which is cosmopolitanin nature, follows the last of the European accents. The CDs also present two types of standard English—a selection of speakers of standard North American, including one Canadian, and a variety of speakers of standard British, several of whom use “received English,” as it used to be called.

None of the dialect groups presented is in any way exhaustive. Those included have been selected to serve the actor’s purpose, not the linguist’s. Some that may have a limited use have been omitted for lack of space. In the North American group, Pennsylvania Dutch, Cajun, Newfoundland and North American Indian dialects are not represented. Nor are many subdialects of the West and South. The Midwestern group on CD One represents only the dialect speech of the extreme southern boundaries of the Midwest, which is a vast region, geographically stretching east from the Rockies to the Alleghenies and north from the Ohio River and from the states of Missouri and Kansas into the Canadian prairie provinces. Its many near-dialects flow and merge into one another, but are most sharply defined in the border examples given.

All dialects at the present time are suffering from erosion, due to the ubiquitous influence of radio and television, and the increasing importance of speech education departments in universities. Dialect traces persist in some areas, especially among the older generation, but are fading from the speech habits of many of the younger generation. A great richness and diversity is thus beginning to pass from common speech. Dialect usage remains, however, as an element in many important plays, and this manual and the CDs aim at preserving source material from living dialects for the actor’s use.

Three or more examples of each dialect or accent are presented on the CDs. These differ more or less from one another, according to the speaker’s back ground or locality. They have been chosen to give the actor a rich source to choose from and the variety that may be necessary for different types of authentic characters. They are in no sense complete linguistic offerings. The standard speech examples, North American and British, are included for two reasons. First, a Canadian or an American actor often needs to use “cultivated” British speech, while British actors frequently need to appear in American or Canadian plays, where standard North American is appropriate. Second, an actor, like any professional person, may wish to standardize his own speech, if it has traces of regionalism. “My dreadful Noo Joisey speech!” cries a student actor in an eastern college. “Ah mun be rid of it, tha knowest!” exclaims the Yorkshire lad in a British drama school. Both need to realize that standard English speech may be learned as one learns a dialect. Not for nothing did the Hungarian professor, hearing Eliza Doolittle’s faultless English at the ball in My Fair Lady, declare, “She speaks English as thosewho have been taught!”

What a character is saying in dialect on the stagemust be comprehended by the audience. If the dialect is too heavy, the audience will miss some of the lines and much of the pleasure they expected, eventually becoming bored and restless. By contrast, the speakers on the CDs may all, with one or two exceptions, be readily understood by either a British or an American ear. When you begin to learn any dialect, bear this in mind: Keep your sound changes few, but consistent. An audience subconsciously recognizes consistency in a speaker’s style and accepts his dialect as genuine.

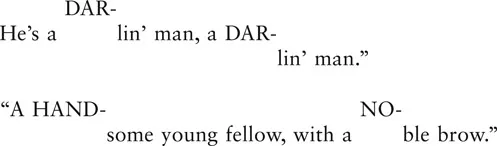

Merely making the selected sound changes of a dialect is not enough. There is also the lilt to learn. This lilt or speech melody is an essential part of each dialect. Irish particularly has its musical rise and fall:

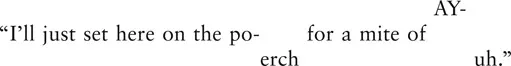

New England Yankee speech has a falling inflection between syllables or even within one:

The pitch and rhythm changes of a dialect make a kind of tune, often with a recurring phrase like a theme in music. It is this element which makes an acquired dialect truly authentic. Be sure to recognize it and learn it. Foreign accents possess lilts too. They are usually the typical inflections of the language, carried over persistently to the English syllables. It happens in French-accented English. “There is a rhythm, a rhythm that one falls into naturally,” says the fourth speaker of that accent (p. 116). In the Italian examples, you will even hear some English words modified to make them fit the native Italian lilt: “The sun-a she’s-a just-a coming up-a” (Italian No. 3, p. 120). You should adopt and follow this feature.

Dialect speaking on the stage must be relaxed and natural. Do not let the use of the sound changes and the lilt put a straitjacket on your acting. Rather wear them so often in improvising in the dialect both out loud and in your head that they come to fit comfortably at last over your regular speech, like a well-worn coat. This effort may take one week; it may take six weeks. After a number of play-it-and-say-it practice sessions, launch into the dialect courageously, in season and out. One of my students did this. He worked hard to acquire a Welsh dialect for The Corn Is Green, so that by performance time he could use the proper lilt and all to great effect in theplay. Later, in a restaurant, student friends asked him to assume it again for fun. Carried away, he let himself go, improvising freely. A waitress, overhearing, came up to themin great excitement. She cried, in her own Welsh accent, “And what part of Wales did YOU come from?”

Because the examples in each dialect differ from each other, you should select as your chief model the one which seems most appropriate for the role you expect to play. How to choose this is discussed further in Part Two. However, always work first with the spaced example, No. 1. It may be the only one you need. Surprisingly, you can become fluent in a dialect working from a single good model if you immerse yourself in it until you have words and tune by heart.

Enjoy these dialects. Learn them for pleasure and for profit. Throw away your inhibitions as you practice. Remember that your own ears will be affronted if not outraged when your own voice speaks in strange accents. Your feedback hearing system will be disturbed at Russian or French-Canadian or Welsh sounds coming out of your mouth, instead of the familiar American, Canadian or British ones. Ignore this feeling, and push on till the new sounds and inflections become your own.

At the end of CD Three, there is a special help for dialect learning, the International Phonetic Alphabet, presented in sound. It is included for actors who learned it once and have forgotten it through disuse and for those who will take the trouble to learn it for the sake of reproducing new pronunciations not met with on the CDs. The IPA, as it is called, spells by sound elements only. One phonetic symbol stands for one sound element, or phoneme, and for that one alone. Many of these symbols are the same as the letters of our regular alphabet. Others are different but easily learned. On CD Three the sounds for the symbols are spoken in groups. They are presented in the same order in Part Eight of this manual. For a fuller treatment of the subject and a methodof learning the IPA easily as you work with your voice, see my Speech for the Stage, Chapters 8 and 11. Once you have learned the IPA, you can write out the sounds of an unfamiliar dialect with absolute accuracy. It is what Professor Higgins of My Fair Lady and Pygmalion was doing that rainy night in London when he first heard Eliza Doolittle’s Cockney.

However, since many actors are unfamiliar with the IPA, words heard on the CDs with dialectal variant sounds are respelled phonetically in this manual, using the ordinary alphabet, not the IPA alphabet. The Southern I, for instance, is respelled Ah. The New York-Brooklynese “shirt” is heard as shoit, and is so respelled. The respelling for each variant is as phonetic as possible. But you must always remember that respelling is suggestive rather than exact as to the pronunciation it representst. Is the best that can be done to show dialectal pronunciations using the letters of the alphabet. The dialect pronunciations that you must learn are those HEARD ON THE CDs. Thereonly can you discover exactly what the respellings are meant to stand for. Guiding yourself by what you hear rather than by what you see, you will safeguard yourself against mistakes in dialect reproduction.

If you are to become an expert in this field you will do well to make the effort to learn the IPA and to use it, not only with the material in these examples, but in working with new material or in writing out dialects as you hear them in life. Reading your transcriptions, you will find you are reproducing exactly what you heard, which is the aim of dialect learning. The IPA gives a total correspondence between what is written and what is heard. Thus, even if you hear a dialect speaker when you have no recording device at hand, you will not lose the opportunity to record his speech. You can immediately make a perfect record in writing and add it to your growing store of dialect information.

2

USING THE DIALECT TEXTS AND THE DIALECT DATA

The complete text of each example in each dialect group is presented in Parts Four, Five, Six and Seven of this manual. The examples are titled and arranged as on the CDs. Additional data are provided with the text as are aids to learning the dialect. For the sake of simplicity, the word “dialect” is used here and throughout the rest of the manual in most cases as a covering term, standing for all the groups, except the two standard forms of English.

The kinds of data presented with the texts of the transcriptions are:

- Spacing Data

- Pronunciation Data

- Inflection Data

- Pronunciation Notes

- Vowel and Consonant Changes

- Colloquialisms and Idioms

- Notes for American, Canadian and British Actors

- Inflection Notes

- Character Notes

- Lists of Records and Plays for Study

Spacing Data

The first example of each group is handled differently from the others in the matter of spacing. It is repeated on the CD in short units, with silent spaces between. The other examples are not repeated; they are heard once only.

When you listen to the first example repeated, you hear a short bit, followed by a silence during which you are to say the bit you just heard. As you finish, the next bit on the CD begins; you repeat this during the next silent space. You continue to do this throughout the repetition of the first example, simply listening to a bit (hereafter called a unit), and saying it during the silent space provided.

With the other examples, you will have to stop and start the CD yourself, and then repeat what you just heard. After repeating it, you start the CD again and listen to the next unit. Then you stop the CD again and repeat that unit. You continue in the same way throughout the example.

To show you where to stop for each unit, the text for each example is broken up by slash lines, single and double. The slashes are stopping places that have been worked out for comfortable repeating of a phrase or sentence. At first, stop the CD every time a single or a double slash is reached, and repeat aloud what you heard. As the material gets familiar, go through the example again, stopping only at the double slashes. Now you will be saying a bit two units long. For instance, Midwestern No. 2 begins:

“This li’l NOOSPAPER clipping is ENTAATLED /

“ ‘Lou Teaches HERRBIE How to Hunt for an Ancient Mule.’ ” //

On the first few rounds, you stop the CD after “ENTAATLED” and repeat to that point. Then you stop it at “Mule” and repeat only the second unit, “Lou Teaches HERRBIE How to Hunt for an Ancient Mule.” You continue so, unit by unit. Later you go through the CD not stopping at “ENTAATLED”/ or at any single slash, but at the double slashes only. With this step, you extend your ability to keep to the dialect.

When a triple slash appears about halfway through one of the longer examples, as in the case of Midwestern No. 2, “he’d take care of the mule,”/// it indicates a special stopping place that divid...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Part One The Actor, the CDs and the Manual

- Part Two Using the Dialect Texts and the Dialect Data

- Part Three Steps in the Play-It-and-Say-It Method of Learning Dialects

- Part Four North American Dialects

- Part Five Standard English: North American and British

- Part Six Dialects of Great Britain and Ireland

- Part Seven European Accents

- Part Eight Symbols and Sounds of the International Phonetic Alphabet

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Dialects for the Stage by Evangeline Machlin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & History of Ancient Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.