eBook - ePub

Information and Communication Technologies in Action

Linking Theories and Narratives of Practice

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Information and Communication Technologies in Action

Linking Theories and Narratives of Practice

About this book

This book combines 20 stories from a variety of organizations with a selection of nine theories, both mainstream and emerging. The stories introduce readers to individuals talking about how they communicate today via information and communication technologies (ICTs) in business or organizational contexts. The theories, presented in accessible language, illuminate the implicit patterns in these stories. This book demonstrates how and why these technologies are used under myriad circumstances.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Information and Communication Technologies in Action by Larry D. Browning,Alf Steinar Saetre,Keri Stephens,Jan-Oddvar Sornes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Communication Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Media Choice and ICT Use

“Media choice” is a term acknowledging that, when communicating, we often have a variety of media available and that our choices reflect many variables. For example, some people choose to use email instead of voicemail. But why? And why do different national and organizational cultures view technologies each in their own way? Why is face-to-face preferred when building a relationship? The 20 narratives in this book illustrate how expert ICT users both choose and use particular ICTs, alone and in combination. For example, they tend to prefer face-to-face in ambivalent and emotionally sensitive situations. While that preference seems to be nearly universal, these same expert users are often inconsistent with respect to their preference for email versus the telephone. In this chapter, we will introduce you to the various theories and research findings that try to explain media-choice behaviors.

Determinism or Social Construction?

Current theories of ICT use tend to fall into two camps. The first is openly deterministic. Theorists who subscribe to this view assume that media choice is invariably rational and thus predictable. For example, they contend that the very features embedded in a particular technology—say, in a fast or slow Internet connection—automatically predict how individuals will browse the Internet.

| Does technology itself determine how it is used, or do we determine for ourselves how we use communication technologies? |

The rival camp’s theory is social construction. Theorists who subscribe to this view assume that technology features and social factors are intertwined, and thus together influence ICT use. To extend our example above, a social constructionist would argue that social variables—e.g., the personal desire to access a certain Web site—are often more important than whether one has a fast or slow connection. In the theory section that follows, we present some of the most popular views on ICT choice and use, looking first at the deterministic views and then at the socially constructed ones.

Technological Determinism: Richness and Conscious Choice

Communication researchers often postulate face-to-face communication as the gold standard and compare all other modes of communication to it. Face-to-face has been considered the ideal communication “channel” because it supposedly has certain unchanging features embedded in it, making it wonderfully versatile. One such feature is the presence of nonverbal cues—for example, facial expressions and hand gestures. Several theories, all of them deterministic, assume that these cues alone make face-to-face the ideal channel (e.g. Short, Williams, & Christie, 1976).

| Key Theory Media Richness |

But another deterministic theory, called “media richness” (Daft & Lengel, 1984; Daft, Lengel, & Trevino, 1987; Trevino, Daft, & Lengel, 1990), posits a more comprehensive view of communication channels. According to media-richness theory, a “rich” channel like face-to-face actually has four useful features:

1. The ability to transmit multiple signals (e.g., nonverbal cues, voice into-nations, and the verbal message itself).

2. The possibility, if not guarantee, of immediate feedback from the receiver.

3. The opportunity to tailor the message to the real-time situation.

4. The ease of incorporating conversational language such as slang and ambiguous references.

A “lean” channel like email, on the other hand, is essentially stripped down and thus lacks these four features. Empirical studies employing this theoretical stance like to rank-order ICTs along a continuum of richness. Face-to-face normally ranks the highest, and text-based ICTs, like email and letters, rank the lowest. But while being “lean” can be a serious handicap, there are occasions when “leanness” is actually preferred.

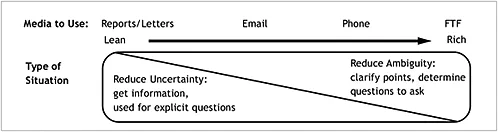

To decide which kind of channel—rich or lean—is preferable in a given case, media-richness theorists use the criterion of “equivocality.” This umbrella term, which is itself a bit equivocal, is applied to two different situations: uncertain ones and ambiguous ones. Uncertain situations are ones where you simply need more

Figure 1-1: Visual Representation of Media Richness Theory

information before you can answer a particular question or complete a task. Ambiguous situations, on the other hand, require you to actually interact with someone—perhaps to explore a next direction, to clarify points, or even to determine what points need clarification. (See Figure 1-1 for a visual representation of this theory.)

Let’s take an example of each situation. Say you want to remodel your house, and you hire an architect. Handling the project with her strictly by email is likely to be unwise. You’ll want to meet face-to-face, study preliminary sketches, hash over likes and dislikes, and then work out a final plan. To achieve all this, a rich channel is ideal—maybe even essential.

But suppose you merely need to tell her that you’ve now chosen granite for your kitchen countertop rather than Formica. Here you’re simply providing a detail to resolve an explicit issue. While you could go to the trouble of arranging a face-to-face meeting to communicate that choice, media-richness theory would remind you that that channel, while effective, would be grossly inefficient here—in effect, overkill.

On the surface, media-richness theory seems eminently logical, in fact incontestable. And it certainly simplifies our thinking about ICTs. We can put them on a nice little menu of if- this, then-that. For example, “If a communication situation is emotional (ambiguous), use face-to-face”; “If you’re conveying an instruction or request, use email.” Such prescriptions guide people to choose the “right” ICT for the job.

Ah, would that it were that simple!

A decade ago, ICT studies using the various deterministic theories began themselves to be scrutinized (Walther, 1992). What we’ve now learned is that there is no clear agreement as to how ICTs should be rank-ordered according to richness. Many things can account for these differences. One variable is national culture. Various studies (e.g. Straub, 1994) comparing media perceptions have found that different cultures can perceive channels very differently. (Rice, D’Ambra, & More, 1998 are an exception because they found very few cultural differences.) In Japan, for example, the fax is considered richer than in the U.S. And some cultures highly value the telephone and business memo.

We’ve also learned that the often-assumed superiority of face-to-face communication over computer-mediated communication (CMC) is actually overstated. Some people who are more practiced using a given ICT will rate it as “richer” than other media, even including face-to-face. And, more surprising still, they report being able, over time, to get a clearer impression of their communication partners that way than if they had actually sat down with them. Furthermore, not all communicators prefer having access to nonverbal cues (Walther & Parks, 2002). Also, in certain situations, asynchronous communication can actually be an advantage. For example, responding via email allows us to ponder, and appropriately time, our response. This will often enhance its quality and thus make email communication ideal.

The Social Construction of ICTs

In the late 1980’s and early 1990’s scholars began to look beyond the rational-choice models to consider the potential influence of social and contextual variables on ICT use. An excellent survey of these theories can be found in Organizations and Communication Technology (Fulk, Schmitz, & Steinfield, 1990). There, scholars criticize rational-choice models for failing to recognize social contexts, task considerations, and organizational variables. But of course including these extra variables makes the social-construction theories both “messier” and more complex, since now we cannot say flatly that a certain channel is always good for a certain situation. As you read the cases in this book, reflect on your own experiences with ICTs and you’ll probably see that you use email differently, at least in some situations, than some other people you know. Social and contextual variables may well explain why that happens.

| Key Theory Social Influence |

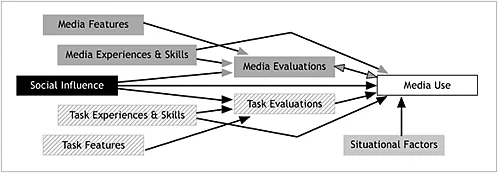

Social influence. One theory in this vein is that of social influence (Fulk, Schmitz, & Steinfield, 1990). Fulk and her associates depart from prior deterministic theories in two primary ways. First, they assume that variables influencing media choice are socially constructed, and second, they claim that the features of both ICTs and tasks are variable. To see how these two major considerations function during ICT choice, we will walk you through their fairly elaborate model.

Figure ...

Table of contents

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1 Media Choice and ICT Use

- 2 The Role of Credibility and Trust in ICT Studies: Understanding the Source, Message, Media, and Audience

- 3 Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations

- 4 A Garbage Can Model of Information Communication Technology Choice

- 5 Impression Management and ICTs

- 6 Enactment and Sensemaking in Organizations

- 7 Giddens’ Structuration Theory and ICTs

- 8 Complexity Theories and ICTs

- 9 ICT and Culture

- 10 The Frustrated Professor

- 11 Teaching the Good Old Boys New Tricks: Taking ICTs to the Bank

- 12 From Blunt Talk to Kid Gloves: The Importance of Adaptability Across Culture

- 13 Slowing Down in the Fast Lane

- 14 Serving the Customer Locally Without Moving There: How to Use ICTs to Project a Local Presence

- 15 Overloaded But Not Overwhelmed: Communication in Inter-Organizational Relationships

- 16 Depending on the Kindness of Strangers: Using Newsgroups for Just-in-Time Learning

- 17 Building a Medical Community Using Remote Diagnosis: The Story of DocNet

- 18 Don’t Get Between Me and My Customer: How Changing Jobs Shifts ICT Use

- 19 Fighting Uncertainty With Intelligence

- 20 Close Up … From a Distance: Using ICTs for Managing International Manufacturing

- 21 Over the Hill but on Top of the World: An Atypical Salesperson

- 22 The Role of ICTs in Maintaining Personal Relationships Across Distance and Cultures

- 23 One in the Hand is Worth Two on the Web: Relying on Tradition When Selling Financial Services

- 24 Do What You Do Well and Outsource the Rest… Even Guarded Information

- 25 Orchestrating Communication: The Process of Selling in the Semiconductor Market

- 26 Nothing Fishy Going on Here: Tracing the Quality of the Seafood Product

- 27 Use of ICTs Following the 9/11 Tragedy From Information to Emotion: The Changing

- 28 Give Me a Cellphone and I’ll Give You Trouble: Technology Usage in a Young Start-Up

- 29 Information Will Get You to Heaven

- Postscript: The Source of Our Stories

- Index

- About the Authors