1 Introduction

This book examines three big ideas: difference, legitimacy, and pluralism. My chief concern is how people construe and deal with variation among fellow human beings. Why under certain circumstances do people embrace, even sanctify differences, or at least begrudgingly tolerate them, and why in other contexts are people less receptive to difference, sometimes overtly hostile to it and bent on its eradication? 1 What are the cultural and political conditions conducive to the positive valorization and acceptance of difference? And, conversely, what conditions undermine or erode such positive views and acceptance?

The term “difference” is arguably straightforward. 2 Dictionary synonyms typically include diversity, variation, multiplicity, and heterogeneity. Scholars who write about the current state of affairs in America, Europe, the postcolonial nations and elsewhere often use one or another of these or kindred terms when discussing some of the more intractable and widespread problems facing contemporary societies, nations, and polities. In much of this writing, heterogeneity involving cultural, religious, ethnic, and racial difference is equated with or subsumed under the rubric of “multiculturalism” or “pluralism” (these terms are frequently used synonymously). The point is commonly made that tolerance, entailing at least partial (or passive) acceptance of difference, is a key condition for the proper functioning if not survival of multicultural or pluralistic societies in nations and states wracked by centrifugal and transnational forces so strong that we seem to be living in “a world in pieces.”3

But is mere tolerance of diversity (such tolerance being an empirically variable phenomenon in any case) truly sufficient, or do those who embody, represent, or champion difference desire something more? And what might that “more” be? The short answer, in my view, is that something more than tolerance is widely sought. As political theorist William Connolly (2005:123) recently put it, “You may have noticed that people seldom enjoy being tolerated that much, since it carries the onus of being at the mercy of a putative majority that often construes its own position to be beyond question.” In this view, the “more” at issue is legitimacy in Max Weber’s (1918 [1968]) sense, which may be characterized for the time being as more or less synonymous with validity insofar as both concepts denote social and cultural processes resulting in assessments—however contested and subject to historical flux—that a given phenomenon is in general accord with one or more subsets of “the norms, values, beliefs, [and] practices … accepted by a group” (Zelditch 2001:33; see also Walzer 1983, 1997, 2004b, Deveaux 2000, Jost and Major 2001, Connolly 2005).4

The arguably commonplace if not banal realization that people seek legitimacy has important implications and does in any case receive abundant support from the ethnographic record. Anthropologists, sociologists, and other professional sojourners the world over are commonly told by the people among whom they work that they want others to recognize that they are human, that their ways of being in the world are just and honorable, in a word, legitimate.5 It is precisely this deeply felt concern that motivates many people to allow anthropologists and like-minded practitioners into their communities and to help them construct accounts of their ways of life which, as they often understand, may be widely disseminated in the outside world.

If people who embody or represent one or another kind of racial, ethnic, religious, sexual, or other difference seek not merely to be tolerated by others but to have their differences accorded legitimacy, then it behooves us to ask whether the societies, states, or other polities in which they live their lives do in fact grant them legitimacy. Put differently, we need to distinguish between the mere existence of diversity in a given setting (society, nation-state, diasporic community) on the one hand, and the manner in which it is dealt with and experienced in that setting on the other. The concept of pluralism is quite useful here, especially if we limit its use to conditions or settings in which diversity is accorded legitimacy. The question then becomes: What are the material and other conditions conducive to pluralism?

The world as a whole obviously constitutes too vast a canvas for depiction of these processes. For this reason, I confine most of my discussion to Southeast Asia, a region in which I have conducted over two and a half years of anthropological fieldwork and have been studying since the early 1970s. Southeast Asia provides intriguing contexts for inquiries bearing on pluralism partly because it has long been known for pluralistic traditions bearing on gender, sexuality, religion, and ethnicity. I hasten to add that as deeply interested as I am in this region, I am less interested in theorizing about it than theorizing from it.

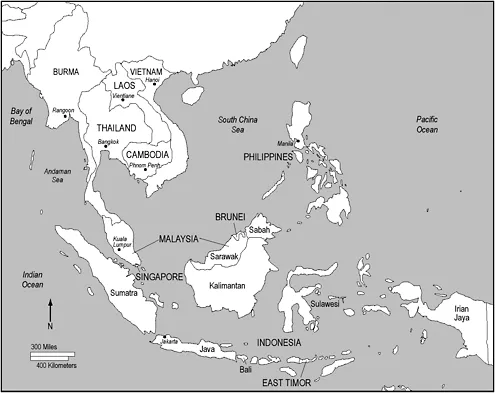

This book examines pluralism in gendered fields and domains in Southeast Asia since the early modern era, which historians and anthropologists of the region commonly define as the period extending roughly from the fifteenth to the eighteenth centuries. Southeast Asia is a vast, heterogeneous region “at once territorially porous, internally diverse, and inherently hybrid” (Steedly 1999a:13) that currently consists of 11 different nation-states and a population of over a half billion people. Hence I should underscore that there are numerous commonalities—in linguistic structures, dietary habits, household construction and public architecture, religious beliefs and practices, patterns of kinship/gender, sexuality, and socio-political organization—that have long underlain the striking diversity of the region (Murdock 1960, Reid 1988, 1993b, Higham 1989, Bellwood 1997, Wolters 1999, B. Andaya 2006). Especially since the end of World War II and the beginnings of the Cold War when the US Government made funding available for scholarly research bearing on strategically defined “area studies,” these commonalities encouraged scholars to approach Southeast Asia as a “culture area” or in terms of a nexus of related, overlapping “culture areas.” Concepts such as “culture areas” may well have outlived their usefulness; and some scholars writing at present prefer to speak of “world areas,” thus emphasizing how certain regions are situated on the world stage, in relation to global flows of capital, technology, labor, and the like that have engendered commonalities possibly overshadowing earlier similarities suggesting the relative coherence of a “culture area” (Knauft 1999, Johnson, Jackson, and Herdt 2000). Whichever of these (or other) terms one uses, it is important to bear in mind that the boundaries of Southeast Asia as a “culture (or world) area” are quite porous and contested, and are not isomorphic with the boundaries of Southeast Asia as a geopolitical region, which is usually defined as including Burma (Myanmar), Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, Indonesia, East Timor, and the Philippines (see Map 1). As earlier generations of scholars (e.g., Murdock 1960) have emphasized, on cultural historical grounds some indigenous peoples of Taiwan merit inclusion in the Southeast Asian “culture area,” as do various groups in and around Madagascar; conversely, most inhabitants of Irian Jaya are usually classified in cultural terms as Melanesian rather than Southeast Asian. Throughout most of this book, I limit the descriptions and analyses of Southeast Asia as a “culture (or world) area” to the region that falls within Southeast Asia’s modern-day geopolitical boundaries, though I also discuss Southeast Asians in the diaspora (particularly the US), and am not concerned with areas such as Irian Jaya.

Map 1.1 Southeast Asia, showing contemporary national boundaries

My work has been inspired by discourses and controversies in a number of related disciplines, some of which bear on the hierarchy of research priorities in the scholarship on gender and sexuality in Southeast Asia and beyond that has developed over the past few decades. For mostly obvious and altogether legitimate reasons, much of the research has concerned women’s experiences and voices, symbols and idioms of femininity, and, to a lesser extent, normative female heterosexualities. Far less developed—especially but not only in terms of sheer volume—is the scholarship bringing feminist and other critical perspectives to bear on understandings and representations of masculinity, and on normative male heterosexualities (Ong and Peletz 1995, Peletz 1996, Wieringa, Blackwood, and Bhaiya 2007). Needless to say, this situation is by no means unique to scholarship on Southeast Asia. What it suggests, though, is that many scholars studying Southeast Asia and other world areas still appear to regard “gender” as a synonym or shorthand for “women.”6 In a similar fashion, one could argue, as have Gayle Rubin (1984, 1994) and Afsaneh Najmabadi (2005:235–237 passim), that the dominant streams of feminist scholarship have long been primarily “about” women and to a lesser extent gender, but not sexuality. Analogous arguments have been advanced with respect to the social sciences in their entirety (Herdt 1993a:12, Weston 1998). One consequence, according to Rubin and others who hold these views, is that the main currents of feminist scholarship, like the social sciences generally, have shed much light on the struggles and aspirations of women faced with political, economic, and other forms of oppression but have been far less theoretically productive in analyzing the cultural politics of sexual diversity. Partly as a response to this situation, recent years have seen the development of variously defined fields of sexuality studies, such as gay and lesbian studies, queer studies, and transgender studies. These fields have gone a long way toward addressing certain of the silences and elisions highlighted by scholars like Rubin. But it is also true, as Kath Weston (1998) and others have pointed out, that some of the reigning perspectives in these fields, which are defined largely in relation to cultural studies and the humanities, suffer from an insularity that reflects their lack of serious engagement with the work of historians, anthropologists, and others concerned with analyzing sexual and gender diversity through time and space.

One of the aims of this book is to help ameliorate the problematic state of scholarship described here. I seek to do this in two ways. First, I range beyond the usual focuses (women, heterosexuality) and analyze gender pluralism in various fields, domains, and more encompassing systems in Southeast Asia since early modern times. And second, I pay particular attention to the practices, roles, and identities of transgendered persons. I use the term transgendered to refer to individuals involved in practices that transcend or transgress majoritarian gender practices, as I explain in due course. One of my basic arguments is that transgendered persons provide a powerful lens through which to view pluralism, partly because for this region and period the vicissitudes of transgenderism index processes that have occurred across a number of culturally and analytically interlocked domains. These processes include: the increased formalization and segregation of gender roles; the distancing of women from loci of power and prestige; the narrowed range of legitimacy concerning things intimate, erotic and sexual; and the constriction of pluralistic gender sensibilities as a whole, which, in recent times (since the 1980s), has gone hand in hand with a proliferation of diversity and the emergence of new loci of legitimacy. More generally, one has to start one’s analysis somewhere, and I argue that transgendered persons and the sexual variability associated with them and their normatively gendered partners provide a productive point of departure for descriptions and analysis of sexual and gender diversity in the region.

An additional set of comments that will help provide context for the discussion that follows has to do with methodology, terminology, and conceptual apparatus. In terms of source material, I draw on indigenous (mostly Malay-language) manuscripts, and on the writings of Chinese, European and other explorers, European colonial officials and missionaries, as well as the research of medical personnel, archeologists, historians, and anthropologists, Asian and Western alike. Many of the published materials available to us through the end of the colonial period were produced by males, often of elite background. The potential for gender- and class-skewed accounts is compounded by factors of race, ethnicity, and religion (among others), especially during late modern times and the colonial era when outsiders had increasingly well formulated designs on the region and its resources. This period saw a profusion of writing by European (mostly Christian, heteronormatively oriented) travelers, missionaries, statesmen, and colonial officials who sought justification for their missionary and other “civilizing” projects in social and cultural difference construed as depravity, perversity, and inversion. The French, for example, typically “constructed the Vietnamese male as androgynous, effeminate, hermaphroditic, impotent, and inverted and, conversely, the Vietnamese female as virile and hypersexualized” (Proschan 2002a:436). The larger issues are that Southeast Asians, like the denizens of most other world areas, were often “represented as a limitless repository of deviance, extravagance, [and] eccentricity” (Bleys 1995:267), and that these topoi “served to demonstrate either the primitiveness or the degeneracy of the population concerned, and the urgent need for civilizing, Christianizing, and otherwise uplifting them” (B. Anderson 1990:277–278). Many of these accounts do not meet current standards of objectivity, are clearly socially situated (as in different ways are their successors), and deal in any case with partial truths (as also, albeit in different ways, do their successors). Some of them nonetheless contain much of value, especially when read with an historical anthropological sensibility that views them against the grain of the more stolid, straitlaced, and balanced scholarship on Southeast Asia produced by historians, anthropologists, and others in the latter half of the twentieth century and the early years of the new millennium. The latter literature provides direct or indirect confirmation of many key observations from earlier times, while disconfirming or raising serious questions (or remaining altogether silent) about the plausibility of others.

Gyanendra Pandey (2006:31–32) has recently noted that owing partly to the nature of the written sources available to historians of South Asia, it is much easier to document the broad contours of political, economic, and religious change than to provide nuanced accounts of the lived experiences and subjectivities of variously defined social actors and their transformations through time. This is true for Southeast Asia (and most other regions of the world) as well, and is especially apparent when dealing with women and various categories of individuals involved in transgender practices and same-sex relations. For even though some of them (queens, consorts, concubines, and certain types of ritual specialists and palace functionaries) drew the attention of Chinese and Western observers armed with pen and paper, others (commoner women, the lay partners of transgendered ritualists, and those whose transgender practices and same-sex relations had no direct connection to formal ritual roles or palace activities) did not necessarily do so. Indigenous manuscripts, often produced by scribes in the employ of Southeast Asian political and/or religious elites, are informed by similar kinds of biases. Owing to factors such as these, we tend not to have access to the voices of “ordinary women (or men)” or individuals who transcended or transgressed heteronormative ideals prior to the twentieth century, even when some of their subject positions and customary practices—and the symbols and meanings associated with them—are fairly well described. This situation is in some ways analogous to that faced by scholars who have studied eunuchs in the Islamic heartlands since the twelfth century, “royal harems” in Ottoman and South Asian contexts (Peirce 1993, Lal 2005) and many other groups “without history” in Eric Wolf’s (1982) sense.

I also draw on the archival research and ethnographic fieldwork that I have conducted in Malaysia since the late 1970s and on professional travel elsewhere in the region (Singapore, Indonesia, Thailand, Burma, Vietnam), mostly since the early 1990s. My research in Malaysia involved two lengthy periods of fieldwork (1978–1980, 1987–1988) totaling some 26 months and a number of shorter visits (1993, 1998, 2001, 2002, 2008). I have discussed fieldwork methods, my fluency in Malay, and my experiences in the field in detail elsewhere (Peletz 1996: Chap. 1, 2002:11–16 passim; cf. 1993b). The main periods of research were undertaken in the state of Negeri Sembilan and focused on kinship/marriage, gender, sexuality, and the cultural politics of Islam and of Islamic courts in particular. In recent times, I have worked mostly in Kuala Lumpur and have concentrated on interviews with judges, lawyers, artists, gay and lesbian activists, and individuals involved with AIDS organizations, Muslim feminist groups (e.g., Sisters in Islam), and other non-governmental organizations (NGOs). I should emphasize that I also draw extensively on anthropological and other works from earlier decades (which are of uneven quality) not to construct a timeless, heavily mythologized Other (Fabian 1983); rather, I regard such accounts as historically situated texts that can help document continuities and transformations in patterns highlighted in the earlier literature.

As for terminology and conceptual apparatus, I use the term “pluralism” to refer to social fields, cultural domains, and more encompassing systems in which two or more principles, categories, groups, sources of authority, or ways of being in the world are not only present, tolerated, and accommodated, but also accorded legitimacy in a Weberian sense (Deveaux 2000, Jost and Major 2001; see also Walzer 1983, 1997, 2004b, Connolly 2005). Legitimacy (“a phenomenon of the ‘social order’” [Zelditch 2001:39]),7 however much contested and in flux owing to dynamics elucidated by Gramsci (1971), is thus a sine qua non for pluralism, which means, by definition, that pluralism is a feature of fields, domains, and systems in which diversity is ascribed legitimacy, and, conversely, that diversity without legitimacy is not pluralism. There are important reasons, both empirical and analytic, to draw a clear distinction between diversity or difference on the one hand, and pluralism, defined succinctly as “difference accorded legitimacy,” on the other. One set of reasons has to do with the fact that the differences that exist in a given milieu may be denied legitimacy and/or stigmatized (Kelly 1993). Another has to do with the fact that the proliferation of difference—defined or experienced in ethnic, racial, religious terms, or with respect to the florescence of consumer or “lifestyle” choices—can easily lead to a constriction of pluralistic sensibilities and dispositions. This is not merely a hypothetical possibility. A proliferation of social and cultural diversity (following large-scale immigration, for example) commonly brings with it new interests, standards, values, and visions. These phenomena sometimes entail not only a direct challenge to existing arrangements and the groups and interests they serve, but also repressive, monistic, or absolutist responses from the powers that be.

Scholarly and political debates involving pluralism and its discontents are rather fraught at this historical juncture. It is thus worthwhile to emphasize that pluralism is always relative, never absolute, and that a society’s commitment to pluralism need not involve, as Clifford Geertz (2000:42) puts it, “the moral and intellectual consequences that are commonly supposed to flow from relativism—subjectivism, nihilism, incoherence, Machiavellianism, ethical idiocy, esthetic blindness, and so on.” There are, in my view, at least three reasons for this. First, all societies delimit within certain ranges what kinds of values, norms, principles, and social practices they take to be legitimate in order to maintain a degree of social order and cultural coherence. Put differently, no society is altogether normless, although some opponents of pluralism (and of what is often referred to as “multiculturalism”) obviously think so. Second, commitments to pluralism in a given society or among variously defined sectors of a society are in some ways analogous to religious faith. To quote Connolly (2005:49), they not only vary in “intensity, content, and imperiousness;” they may also be more discernible in dispositions and sensibilities than in formal creed or doctrine. And third, pluralism in a given society, like justice, equality, and hierarchy, tends to be domain specific, just as within a particular domain it tends to suffuse certain realms (arenas, offices, subjectivities) and not others. Thus, pluralistic sentiments regarding religious affiliation or ethnic identity, for instance, may not inform collective thought bearing on erotic preferences, and vice versa.

These observations have important implications. In Southeast Asian societies of the early modern period, the range of erotic activities and other bodily practices sanctioned by cosmologies, mythologies, and the ritual specialists charged with mediating relations between humans and world of the sacred was far more expansive than in late modern times. But that range was clearly bounded; it had limits. There were clear normative expectations bearing on “close mating” (incest), exogamy, and extra-marital relations, for example; and in some instances their infraction required that transgressors be exiled from the community, boiled in pitch or molten metal, or subject to other gruesome punishment. The existence of a largely implicit “heterogender matrix” is relevant here as well. For while it allowed for and in some contexts encouraged sexual relations and marriage between individuals with similar anatomies as long as they were held to be differently gendered, it made little if any provision for sexual relations or marriage involving persons viewed as identically gendered. Indeed, relations of the latter sort appear to have been beyond the pale of local thought and experience.

The always already circumscribed nature of pluralism raises other issues having to do with processes involving the cultural conceptualization and analytic marking out of domains, processes that Marilyn Strathern (1988, 1992) refers to as “domaining.” These matters merit brief remark insofar as they help...