- 305 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The title is just the first of many startling asides, observations and insights that fill this guide to Hollywood on the Lacanian psychoanalyst's couch.

Zizek introduces the ideas of Jacques Lacan through the medium of American film, taking his examples from over 100 years of cinema, from Charlie Chaplin to The Matrix and referencing along the way such figures as Lenin and Hegel, Michel Foucault and Jesus Christ.

Enjoy Your Symptom! is a thrilling guide to cinema and psychoanalysis from a thinker who is perhaps the last standing giant of cultural theory in the twenty-first century.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Enjoy Your Symptom! by Slavoj Zizek in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

WHY DOES A LETTER ALWAYS ARRIVE AT ITS DESTINATION?

1.1 DEATH AND SUBLIMATION: THE FINAL SCENE OF CITY LIGHTS

The trauma of the voice

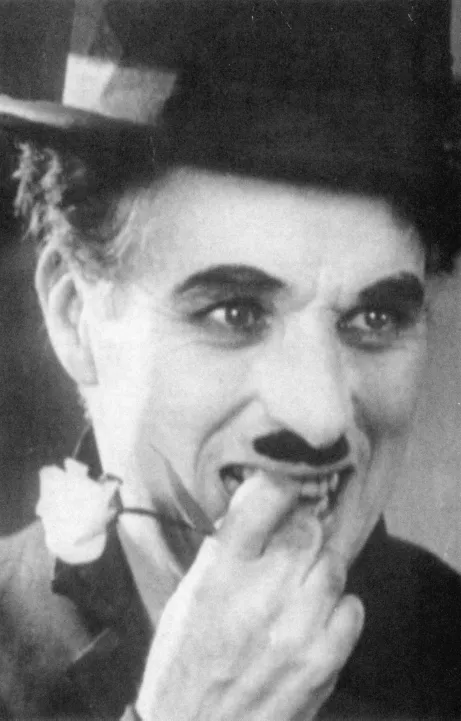

It may seem peculiar, even absurd, to set Chaplin under the sign of “death and sublimation”: is not the universe of Chaplin’s films, a universe bursting with nonsublime vitality, vulgarity even, the very opposite of a damp romantic obsession with death and sublimation? This may be so, but things get complicated at a particular point: the point of the intrusion of the voice. It is the voice which corrupts the innocence of the silent burlesque, of this pre-Oedipal, oral-anal paradise of unbridled devouring and destroying, ignorant of death and guilt: “Neither death nor crime exist in the polymorphous world of the burlesque where everybody gives and receives blows at will, where cream cakes fly and where, in the midst of the general laughter, buildings fall down. In this world of pure gesticularity, which is also the world of cartoons (a substitute for lost slapstick), the protagonists are generally immortal … violence is universal and without consequences, there is no guilt.”1

The voice introduces a fissure into this pre-Oedipal universe of immortal continuity: it functions as a strange body which smears the innocent surface of the picture, a ghost-like apparition which can never be pinned to a definite visual object; and this changes the whole economy of desire, the innocent vulgar vitality of the silent movie is lost, we enter the realm of double sense, hidden meaning, repressed desire—the very presence of the voice changes the visual surface into something delusive, into a lure: “Film was joyous, innocent and dirty. It will become obsessive, fetishistic and ice-cold.”2 In other words: film was Chaplinesque, it will become Hitchcockian.

It is therefore no accident that the advent of the voice, of the talking film, introduces a certain duality into Chaplin’s universe: an uncanny split of the figure of the tramp. Remember the three great Chaplin talking films: The Great Dictator, Monsieur Verdoux, Limelight, distinguished by the same melancholic, painful humor. All of them turn on the same structural problem: that of an indefinable line of demarcation, of a certain feature, difficult to specify at the level of positive properties, the presence or the absence of which changes radically the symbolic status of the object:

Between the small Jewish barber and the dictator, the difference is as negligible as that between their respective moustaches. Yet it results in two situations as infinitely remote, as far opposed as those of victim and executioner. Likewise, in Monsieur Verdoux, the difference between the two aspects or demeanours of the same man, the lady-assassin and the loving husband of a paralysed wife, is so thin that all his wife’s intuition is required for the premonition that somehow he “changed.” … the burning question of Limelight is: what is that “nothing,” that sign of age, that small difference of triteness, on account of which the funny clown’s number changes into a tedious spectacle?3

This differential feature which cannot be pinned to some positive quality is what Lacan calls le trait unaire, the unary feature: a point of symbolic identification to which clings the real of the subject. As long as the subject is attached to this feature, we are faced with a charismatic, fascinating figure; as soon as this attachment is broken, all that remains is dreary remnants. The crucial point, however, not to be missed is how this split is conditioned by the arrival of the voice, i.e., by the very fact that the figure of the tramp is forced to speak: in The Great Dictator, Hinkel speaks, while the Jewish barber remains closer to the mute tramp; in the Limelight, the clown on the stage is mute, while the resigned old man behind the stage speaks …

Chaplin’s well-known aversion to sound is thus not to be dismissed as a simple nostalgic commitment to a silent paradise; it reveals a far deeper than usual knowledge (or at least presentiment) of the disruptive power of the voice, of the fact that the voice functions as a foreign body, as a kind of parasite introducing a radical split: the advent of the Word throws the human animal off balance and makes of him a ridiculous, impotent figure, gesticulating and striving desperately for a lost balance. Nowhere is this disruptive force of the voice made clearer than in City Lights, in this paradox of a silent movie with a sound track: a sound track without words, just music and a few typified noises of the objects. It is precisely here that death and the sublime erupt with full force.

The tramp’s interposition

In the whole history of cinema, City Lights is perhaps the purest case of a film which, so to speak, stakes everything on its final scene—the entire film serves ultimately only to prepare for the final, concluding moment, and when this moment arrives, when (to use the final phrase of Lacan’s “Seminar On ‘The Purloined Letter’”) “the letter arrives at its destination,”4 the film can end at once. The film is thus structured in a strictly “teleological” manner, all its elements point toward the final moment, the long-awaited culmination; which is why we could also use it to question the usual procedure of the deconstruction of teleology: perhaps it announces a kind of movement toward the final denouement which escapes the teleological economy as depicted (one is even tempted to say: reconstructed) in deconstructionist readings.5

City Lights is a story about a tramp’s love for a blind girl selling flowers on a busy street who mistakes him for a rich man. Through a series of adventures with an eccentric millionaire who, when drunk, treats the tramp extremely kindly, but when sober fails even to recognize him (was it here that Brecht found the idea for his Puntilla and his Servant Matti?), the tramp gets his hands on the money needed for an operation to restore the poor girl’s sight; whereupon he is arrested for theft and sentenced to prison. After he has done his time, he wanders around the city, alone and desolate; suddenly, he comes across a florist’s shop where he sees the girl. The operation was successful and she now runs a thriving business, but still awaits the Prince Charming of her dreams, whose chivalrous gift enabled her sight to be restored. Every time a handsome young customer enters her shop, she is filled with hope; and time and again disappointed on hearing the voice. The tramp immediately recognizes her, whereas she doesn’t recognize him, because all she knows of him is his voice and the touch of his hand: all she sees through the window (separating them like a screen) is the ridiculous figure of a tramp, a social outcast. Upon seeing him lose his rose (a souvenir of her), she nevertheless takes pity on him, his passionate and desperate gaze stirs her compassion; so, not knowing who or what awaits her, still in a cheerful and ironic mood (she comments to her mother in the store: “I’ve made a conquest!”), she steps out on the pavement, gives him a new rose and presses a coin into his hand. At this precise moment, as their hands meet, she finally recognizes him by his touch. She is immediately sobered and asks him: “You?” The tramp nods and, pointing to her eyes, asks her: “You can see now?” The girl answers: “Yes, I can see now”; the film then cuts to a medium close-up of the tramp, his eyes filled with dread and hope, smiling shyly, uncertain what the girl’s reaction will be, satisfied and at the same time insecure at being so totally exposed to her—and this is the end of the movie.

On the most elementary level, the poetic effect of this scene is based on the double meaning of the final exchange: “I can see now” refers to the restored physical sight as well as to the fact that the girl sees now her Prince Charming for what he really is, a miserable tramp.6 This second meaning sets us at the very heart of the Lacanian problem: it concerns the relation between symbolic identification and the leftover, the remainder, the object-excrement that escapes it. We could say that the film stages what Lacan, in his Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, calls “separation,” namely the separation between I and a, between the Ego Ideal, the subject’s symbolic identification, and the object: the falling out, the segregation of the object from the symbolic order.7

As Michel Chion pointed out in his brilliant interpretation of City Lights,8 the fundamental feature of the figure of the tramp is his interposition: he is always interposed between a gaze and its “proper” object, fixating upon himself a gaze destined for another, ideal point or object—a stain which disturbs “direct” communication between the gaze and its “proper” object, leading the straight gaze astray, changing it into a kind of squint. Chaplin’s comic strategy consists in variations of this fundamental motif: the tramp accidentally occupies a place which is not his own, which is not destined for him—he is mistaken for a rich man or for a distinguished guest; on the run from his pursuers, he finds himself on a stage, all of a sudden the center of the attention of numerous gazes … In Chaplin’s films, we even find a kind of wild theory of the origins of comedy from the blindness of the audience, i.e., from such a split caused by the mistaken gaze: in The Circus, for example, the tramp, on the run from the police, finds himself on a rope at the top of the circus tent; he starts to gesticulate wildly, trying to keep his balance, while the audience laughs and applauds, mistaking his desperate struggle for survival for a comedian’s virtuosity—the origin of comedy is to be sought precisely in such cruel blindness, unawareness of the tragic reality of a situation.9

In the very first scene of City Lights, the tramp assumes such a role of stain in the picture: in front of a large audience, the mayor of the city unveils a new monument; when he pulls off the white cover, the surprised audience discovers the tramp, sleeping calmly in the lap of the gigantic statue; awakened by the noise, aware that he is the unexpected focus of attention of thousands of eyes, the tramp attempts to descend the statue as quickly as possible, his bumbling efforts triggering bursts of laughter … The tramp is thus an object of a gaze aimed at something or somebody else: he is mistaken for somebody else and accepted as such, or else—as soon as the audience becomes aware of the mistake—he turns into a disturbing stain one tries to get rid of as quickly as possible. His basic aspiration (which serves as a clue also for the final scene of City Lights) is thus finally to be accepted as “himself,” not as another’s substitute—and, as we shall see, the moment when the tramp exposes himself to the gaze of the other, offering himself without any support in ideal identification, reduced to his bare existence of objectal remainder, is far more ambiguous and risky than it may appear.

The accident in City Lights that triggers the mistaken identification occurs shortly after the beginning. Running from the police, the tramp crosses the street by passing through cars that are blocking it in a traffic jam; when he steps out of the last car and slams its rear door, the girl automatically associates this sound—the slam—with him; this and the rich payment—his last coins—that the tramp gives to her for a rose, generate in her the image of a benevolent and rich owner of a luxury car. Here, a homology with the no-less-famous initial misunderstanding in Hitchcock’s North by Northwest offers itself automatically, i.e., the scene where, because of a contingent coincidence, Roger O. Thornhill is mistakenly identified as the mysterious American agent George Kaplan (he makes a gesture toward the hotel clerk exactly as the clerk enters the saloon and cries out: “Phone call for Mr. Kaplan!”): here also, the subject accidentally finds himself occupying a certain place in the symbolic network. However, the parallel goes even further: as is well known, the basic paradox of the plot in North by Northwest is that Thornhill is not simply mistaken for another person; he is mistaken for somebody who doesn’t exist at all, for a fictitious agent concocted by the CIA to divert attention from its real agent; in other words, Thornhill finds himself occupying, filling out, a certain empty place in the structure. And this was also the problem which caused so many delays when Chaplin was shooting the scene of the mistaken identification: the shooting dragged on for months and months. The result didn’t satisfy Chaplin’s demands as long as Chaplin insisted on depicting the rich man for whom the tramp is mistaken as a “real person,” as another subject in the film’s diegetic reality; the solution came about when Chaplin realized, in a sudden insight, that the rich man didn’t have to exist at all, that it was enough for him to be the poor girl’s fantasy formation, i.e., that in reality, one person (the tramp) was enough. This is also one of the elementary insights of psychoanalysis. In the network of intersubjective relations, every one of us is identified with, pinned down to, a certain fantasy place in the other’s symbolic structure. Psychoanalysis sustains here the exact opposite of the usual, commonsense opinion according to which fantasy figures are nothing but distorted, combined, or otherwise concocted figures of their “real” models, of people of flesh and blood that we’ve met in our experience. We can relate to these “people of flesh and blood” only insofar as we are able to identify them with a certain place in our symbolic fantasy space, or, to put it in a more pathetic way, only insofar as they fill out a place preestablished in our dream—we fall in love with a woman insofar as her features coincide with our fantasy figure of a Woman, the “real father” is a miserable individual obliged to sustain the burden of the Name of the Father, never fully adequate to his symbolic mandate, and so forth.10

The function of the tramp is thus literally that of an intercessor, middleman, purveyor: a kind of go-between, love messenger, intermediary between himself (i.e., his own ideal figure: the fantasy figure of the rich Prince Charming in the girl’s imagination) and the girl. Or, insofar as this rich man is ironically embodied in the eccentric millionaire, the tramp mediates between him and the girl—his function is ultimately to transfer the money from the millionaire to the girl (which is why it is necessary, from the point of view of the structure, that the millionaire and the girl never meet). As Chion showed, this intermediary function of the tramp can be detected through the metaphoric interconnection between two consecutive scenes which have nothing in common on the diegetic level. The first takes place in the restaurant where the tramp is treated by the millionaire: he eats spaghetti in his own way, and when a coil of confetti falls on his plate, he mistakes it for spaghetti and swallows it continuously, rising up, standing on his toes (the confetti hangs from the ceiling like a kind of heavenly manna), until the millionaire cuts it off; an elementary Oedipal scenario is thus staged—the confetti band is a metaphorical umbilical cord linking the tramp to the maternal body, and the millionaire acts as a substitute father, cutting his links with the mother. In the next scene, we see the tramp at the girl’s place, where she asks him to hold the wool for her to coil into a ball; in her blindness, she accidently grabs the tip of his woollen underwear which projects from his jacket and starts to unfold it by pulling the thread and rolling it up. The connection between the two scenes is thus clear: what he received from the millionaire, the swallowed food, the endless spaghetti band, he now secrets from his belly and gives to the girl.

And—herein consists our thesis—for that reason, in City Lights, the letter twice arrives at its destination, or, to put it another way, the postman rings twice: first, when the tramp succeeds in handing over to the girl the rich man’s money, i.e., when he successfully accomplishes his mission as the go-between; and second, when the girl recognizes in his ridiculous...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface to the Routledge Classics Edition

- Introduction to the Revised Edition

- Introduction

- 1 Why Does a Letter Always Arrive at Its Destination?

- 2 Why is Woman a Symptom of Man?

- 3 Why is Every Act a Repetition?

- 4 Why Does the Phallus Appear?

- 5 Why Are There Always Two Fathers?

- 6 Why is Reality Always Multiple?

- Index