![]()

| PART | |

| 1 | CREATIVE PLACES |

| Geocreativity |

| Michael Dear |

Conventional social theory makes an important distinction between structure and agency, that is, between the enduring, deep-seated practices that undergird society and the everyday voluntaristic behavior of individuals. This dichotomy is important for what it can tell us about the relative importance of social constraint and free will, and how these opposing forces become articulated in the practices of everyday life. Approaches to the study of the production of place tend to fall into these two categories. Most of the structuralist visions of place production derive out of a Marxist-inspired political economy, including Lefebvre’s concept of the production of space, and Harvey’s treatment of the capitalist urban process. An agency-oriented view of place production has a diverse theoretical heritage that includes material concerns but also cognitive, cultural, and social dimensions (such as attitudes and beliefs, feelings and emotions).

Social theory is also concerned to articulate the relation between social process and spatial structure, that is, how social forces become manifest in geographies, and how geography is constitutive of social relations – a problematic sometimes referred to as the “socio-spatial dialectic.” Needless to say, the relationships articulating society and space relate to more than pure theory; they also have consequences for the work of practicing professionals such as architects and urban planners who are charged with forging new geographies of the built environment.

The spaces of cities are of special concern in this book. While consensus has it that we have entered a global urban age, there is little understanding of, much less agreement about, what this trend entails. The proliferation of urban sprawl has caused investigators to look more closely at the forms of emerging urbanism, but the rash of neologisms describing these forms is more indicative of intellectual confusion rather than understanding. These terms include such descriptors as polycentric, postmodern, patchwork, splintered, and post-(sub)urban. The places produced by these altered processes are variously labeled as city-region, micropolitan region, exopolis, edge city, or metroburbia. Despite the profusion of terminology, there is a growing sense that the geography of cities is changing; no longer are cities being built from the inside out (from core to periphery) but from the outside in (from hinterlands to what remains of the core). This decentered urbanism has the effect of shifting the traditional bases of power in the city. Power lies less in the center than at the edges, and is correspondingly more dispersed, even hidden; but such arrangements also offer greater opportunities for widespread local autonomies. At the same time, other dynamics of the Information Age, such as globalization, domestic and international migration, and so on, underscore how local outcomes in city-regions are being buffeted by forces operating at different scales, including the national and international.

Each of the essays in this section addresses the question of place production in cities, with special emphasis on the creative process in urban places. Cities have always been regarded as the locus of innovation and social change in all dimensions of human activity. In this section’s first essay, geographer Michael Dear considers some fundamentals in the relationship between place and creativity. He distinguishes between creativity in place and creativity of place: the former refers to the role that a particular location has in facilitating the creative process; the latter to the ways in which place becomes an artifact in the creative output, be it a dance movement or photographic frame. Dear describes a two-year collaborative project among an international group of academics, artists, critics, and curators charged to imagine reconstructed places along the controversial and rapidly changing US–Mexico borderlands.

The urban outcomes that characterize the Information Age are dramatically described in architect René Peralta’s account of the border city of Tijuana, in Baja California. One of North America’s fastest-growing and most dynamic cities, Tijuana is globally engaged through the presence of the maquiladora (assembly-plant) industry, a hemispheric trade in drug and human trafficking, and its locus as the busiest international boundary crossing in the world. Peralta’s reading of Tijuana’s urban ecologies rewrites many conventions of urban theory, and reveals some of the startling material conditions of Information Age urbanism.

Cities also have a “soft” dimension, that is, they comprise an infinite number of mental maps lodged in the minds of their inhabitants. To see how these cognitive maps are formed, artist kanarinka invited residents of the city of Cambridge, Massachusetts, to rename their favorite streets and places. The soft city she discovered is full of humanity, invention, and fun, totally unlike the “hard” city with its ponderous monuments, commemorative namings, patrolled spaces, and formal geometries. Produced with friends from the Institute for Infinitely Small Things – itself worthy of attention – kanarinka’s hypothetical map of a city formerly known as Cambridge shows just how deep is the fissure between the formalities of the hard city and the spontaneities of the soft city.

Similar lessons about cognitive mapping come out of architect/artist Gustavo Leclerc’s visual and textual reflection on his migrant experience. Born in Veracruz, Mexico, but now a long-term resident of Los Angeles, California, Leclerc presents a selection from notebooks of his experience of transition to the USA. His drawings were accompanied by textual annotations, also reproduced here, including a grandmother’s recipe and quotes from Mesoamerican manuscripts. In addition, Leclerc has added a present-day commentary to the elements of drawing and annotation. This triple-layered narrative stretches backwards and forwards through time and space in a continuous unfolding reminiscent of the ancient codices (scrolls) of Mayan and other indigenous populations. The syncopated texts bleed into one another, echoing and fusing, making tangible the elusive workings of memory in our lives.

Keeping in mind these introductions to the hard city, soft city, and memory, the following essays turn to the ways creative people work with and in creative places. First, geographer Trevor Paglen outlines what he calls “experimental geography.” Careful to avoid precise definitions and always welcoming nuance, Paglen is nevertheless clear about what he does: he deliberately works in many fields simultaneously; is passionately transdisciplinary and collaborative; communicates through popular media and academic publications; is self-consciously aware of the political in his work; and possesses a keen sense of public responsibility regarding his work. His testimony may amount to a kind of manifesto of experimental geography, but Paglen resolutely refuses this label as contrary to the open-ended, participatory spirit of what he advocates and practices.

Emily Scott’s offers a kind of “undisciplined geography.” She is an art historian and artist, and self-described “long-time interloper” attracted by geography’s breadth and interdisciplinarity. From a base in contemporary art, she asserts that geographers and artists should break boundaries with their undisciplined geographies, drawing on three examples to make her case. Scott is a founder of another activist collective (called the Los Angeles Urban Rangers), which seems to be a common feature of many geohumanities projects.

The centrality of the map as an analytical focus and inspiration is strongly evident in an essay by architect Martin Hogue. He reports on a painstaking documentation of the state of properties and sites in the borough of Queens, New York. Hogue is most interested in what he terms the “agency of the map,” that is, what the map gives to us. He shows the possibilities offered by a map for contemplation and taking stock, as well as the satisfaction he derived from its comprehensive accounting of place. Hogue’s absorption in the map is driven by many desires: a taxonomic urge that seems almost akin to rational and scientific reasoning; but also by flights of imagination. As in Leclerc’s essay, the multiple layers of accumulated meaning dissolve the boundaries between categories and offer opportunities for original insight into both object and observer.

In 1999, Emily Scott recalled cultural geographer Denis Cosgrove’s comment on the “startling explosion” of interest in cartography, the cartographic trope and the map within the humanities and cultural studies. This observation remains current, but a decade later we are witnessing a more general “spatial turn” that is emblematic of the geohumanities project as a whole. In this opening section on geocreativity and the production of place, our contributors have already illuminated some of the geohumanities’ strategies: a proclivity to transgress disciplinary boundaries; to accumulate layer upon layer of transdisciplinary data, and then make connections; to imagine the world as well as describe it; and to produce scholarship, art, poetry, community, and politics (often simultaneously) from their works. The inventive, edgy settings inhabited by these practitioners occur in many places: five of the essays in this first selection focus in some way on California and the US–Mexico border, the latter a place of great turmoil and potential; but creativity also occurs in older more established urban places, sometimes driven by small collaboratives dedicated to their communities. Another preliminary observation relates to the social-theoretic question of structure and agency: even at this early stage in our exegesis, a geohumanities approach appears to promise greater insight into the question of human agency in its myriad forms and dynamics.

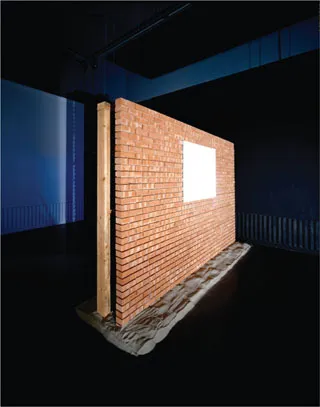

Figure 1.1 Walls, Muros. Source: Marcos Ramirez. Used by permission.

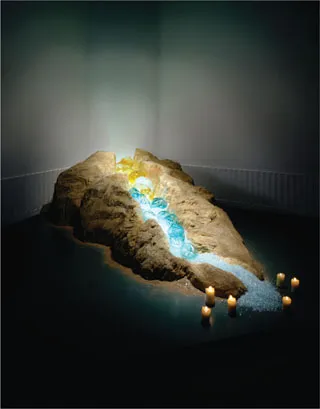

Figure 1.2 What the River Gave Me. Source: Amalia Mesa-Bains. Used by permission.

![]()

1

Creativity and place

Michael Dear

Place

Creativity takes place. That is to say, it occurs in specific locations, but also it requires space for its realization. Creativity in place refers to the role that a particular location, or time-space conjunction, has in facilitating the creative process: think for example of fin-de-siècle Vienna, Silicon Valley, or Hollywood. Creativity of place refers to the ways in which space itself is an artifact in the creative practice or output, as when a dancer moves an arm through an arc or a photographer crops an image to create a representational space. The simplest creative acts are fraught with geographies that instruct the spectator how to see, but also hide things from us.

Most artists readily concede the significance of place in the creative process. For instance, director Peter Sellars found in California a delightful sense of playful experimentation and an important freedom from overbearing tradition:

This is the place where people have come to try new things. It’s the newest edge of America … New York and Chicago remind you of what America was. In California, the question is, what will America be?1

Amalia Mesa-Bains, a Chicana scholar and artist, reminds us of the complications of identity:

all the time California has been California, it’s always been Mexico. There is a Mexico within the memory, the practices, the politics, the economy, the spirituality of California.2

And novelist Carolyn See reveals how the specificity of space adds universality to her fiction:

When I talk to my students about writing, I talk about characters and plot, space and time, but, most important, geography. Place has always been where you start. The more specific you can get about a particular place, the better chance you have of making it be universal and of really grounding it.3

The inspiration provided by geography is, in short, a rich and robust wellspring that operates in myriad ways.4 The city itself may become a crucible of artistic innovation whenever a critical mass of artists is assembled. Perhaps the most famous...